The following essay was originally compiled for the Mixed Migration Review 2021 and has been reproduced here for wider access through this website’s readership.

The essay’s author Mark Akkerman is a researcher at Stop Wapenhandel (Dutch Campaign Against Arms Trade) and works with the Transnational Institute on the topic of border militarisation. He has also written and campaigned on issues such as arms exports to the Middle East, the private military and security sector, greenwashing the arms trade, and the militarisation of climate change responses.

The ballooning business of securitising migration and militarising borders is worth billions of dollars. As a self-interested private sector strives to steer public policy towards seeing those on the move as a threat requiring costly mitigation, mixed migration itself is becoming increasingly perilous.

On 1 October 2020 EU’s border and coastguard agency, Frontex, concluded contracts worth up to €50 million with arms companies Airbus, Israel Aerospace Industries, and Elbit, for drone border surveillance services in the Mediterranean. That same month, at least 612 people died trying to cross this sea. These figures are not just a snapshot, they are exemplary of the two sides of the EU’s militarised border policies: while military and security companies have raked in billions of euros providing equipment and services for a continuous increase in border security and control, thousands and thousands of migrants have died trying to reach Europe, or have ended up being detained, deported or forced to live in inhumane circumstances in refugee camps or as “illegals”. Borders mean death for some, profits for others.

The border security and control market

The international market for border security and control is growing rapidly. Recent market research reports predict large growth in specific fields. The border security market is set to see annual growth of between 7.2% and 8.6%, reaching a total of $65-68 billion by 2025. Europe stands out with an anticipated annual growth rate of 15%. Large expansion is also expected in the global biometrics and artificial intelligence (AI) markets, which have a considerable border- and migration-control component.

Yet, compared to the global military market, which rose to $1,981 billion in 2020, the border security market is still quite small. There are other aspects that make it important for the military and security industry though, such as diversifying portfolios so as not to be dependent on one specific thematic market. Only recently has the EU begun to fund military research and the development of new arms, while funding for security research has been a part of EU Framework Programmes for research for many years. Border security exports can help open up markets in a broader sense by introducing a company to the relevant authorities. And borders are also an ideal testing ground for new technologies, because their use there seldom stirs up much controversy and debate. Refugees and migrants “often become guinea pigs on which to test new surveillance tools before bringing them to the wider population”.

Industrial lobby

The importance of the border security and control market for the military and security industry has spurred a lobby which has significant influence in shaping Europe’s border and migration policies. The two leading lobby organisations of the European military and security industry are the Aerospace and Defence Industries Association of Europe (ASD) and the European Organisation for Security (EOS). EOS has been most active on the topic of border security. In the field of biometrics, an important growth market, the European Association for Biometrics (EAB) is the primary industry organisation. Its close relations to EU authorities are visible in that Frontex and eu-LISA (European Union Agency for the Operational Management of Large-Scale IT Systems in the Area of Freedom, Security and Justice) officials participate in EAB’s advisory council. Moreover, large arms companies also have their own lobby offices in Brussels, the centre of European power.

Company lobbyists and representatives of these lobby organisations regularly meet with EU institutions, including the European Commission and Frontex; are part of official advisory committees; publish influential proposals; organise meetings between industry, policy-makers and executives; and meet at many military and security fairs; conferences, and seminars around the world.

Industrial lobbying also plays a role in shaping US and Australian border and migration policies, where company donations to political candidates and representatives is an aspect of lobbying efforts that is less seen in Europe. In the US, candidates from both major parties received tens of millions of dollars in donations during the 2020 election campaign. Canstruct, a company that earned over A$120 million ($90 million) managing the Australian detention centre in Papua New Guinea, is linked to at least 11 donations to Australia’s ruling coalition government between 2017 and 2020.

Policies of securitisation and militarisation

While the military and security industry is not alone in trying to shape Europe’s border and migration policies, it has been and remains influential in setting the underlying narrative, pushing for concrete proposals, and subsequently implementing them.

Regarding the narrative, the industry has framed mixed migration as a security problem, portraying refugees and migrants as a threat to Europe. Once an issue has been defined in terms of a security problem, a militarised response to solve it becomes the next logical step. The EU and its member states have been firmly on this course for many years already, deploying military personnel and equipment to the borders to stop migration, launching military Operation Sophia around the Libyan coast, building a standing border guard corps for Frontex, and so on. Here the industry stands ready with a constant flow of new equipment and technologies, presenting them as necessary to deal with (irregular) migration. In parallel, it promotes new policies, which offer opportunities for sales, and budget increases for spending on border security and control.

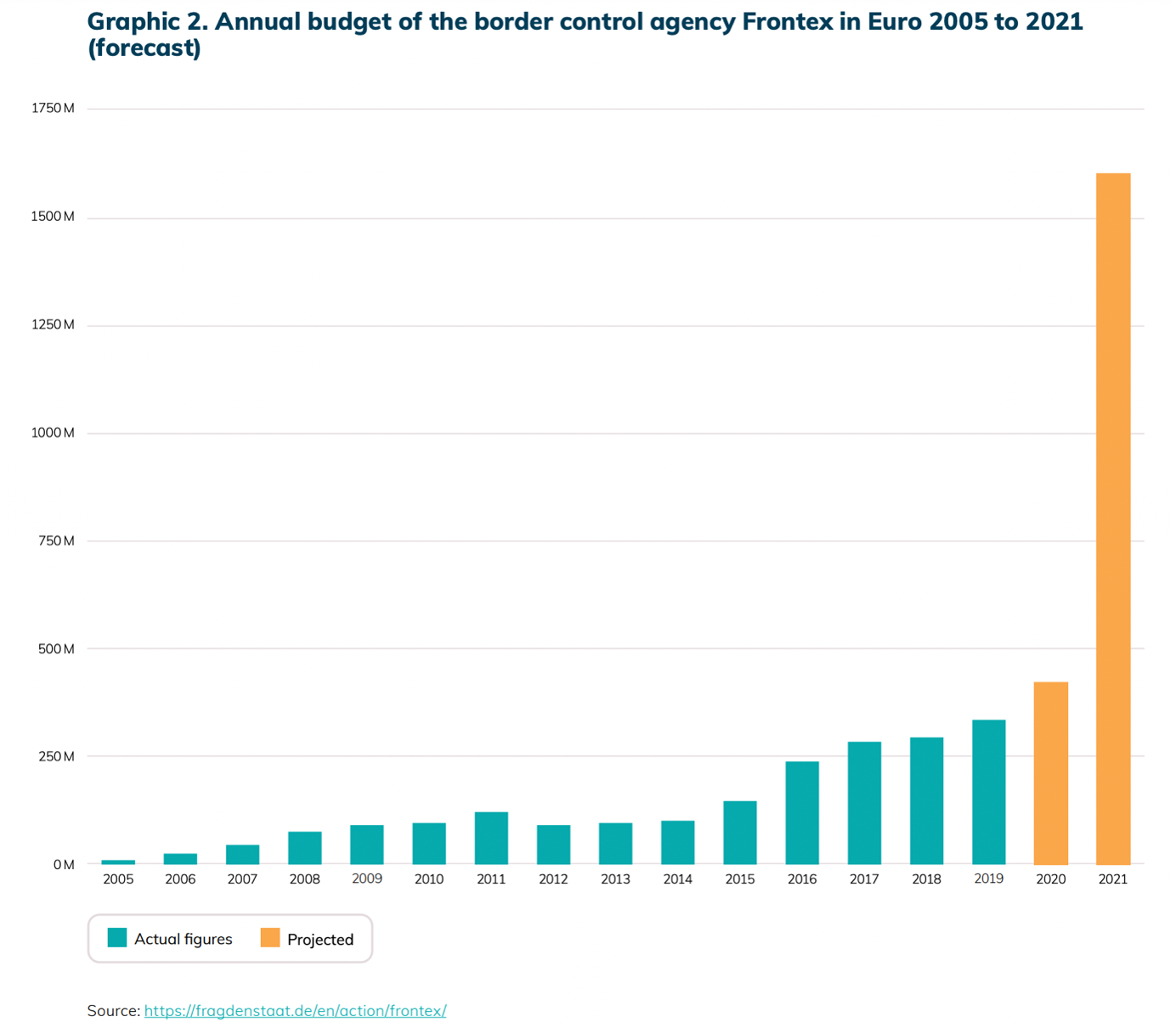

The ongoing expansion of Frontex from an agency coordinating EU member states’ border security efforts into a more independent border guard agency, with its own standing border guards corps and equipment for border security operations, with a budget that has been rising rapidly since 2015, had for example been proposed by the industry for several years before. In September 2010, EOS already proposed the creation of “an EU level Border Guards capability able of supporting MS [member states] interventions, providing resources in case of crisis with a capability for basin-wide monitoring, directly operated by Frontex and using, where appropriate, aerial visualization”.[1]

Another example, where a proposal from the industry was mirrored almost exactly by a subsequent European Commission proposal, is the Instrument contributing to Stability and Peace (IcSP), which was established as a fund to support peace-building and crisis response in non-EU countries. Lobby organisation ASD in 2016 proposed broadening the criteria of the fund, allowing for the supply of non-lethal security equipment and services for “border control” and “counter-terrorism”. This was precisely what happened: the EU opened up the IcSP to cover military and security “training, mentoring and advice, the provision of non-lethal equipment, infrastructure improvements and other services” and increased the budget. Meanwhile, even before adopting these changes, the IcSP had already been used to finance the €20-million purchase of six vessels from Dutch shipbuilder Damen for the Turkish coast guard, to expand its border patrol capacities.

More recently, the industry has jumped on the Covid-19 pandemic to argue for more border security and control efforts. In April 2020, EOS stated that “Europe needs to increase its resilience against present and future threats, both of natural and malicious origin” and that “the EU will need to manage its external borders to prevent the uncontrolled entry of people infected by transmissible pathogens”. Somewhat understandably, many countries set up more rigid border controls during the pandemic to contain the spread of the virus, but it is highly likely that at least part of the new measures will stay in place after the immediate threat of the pandemic has subsided, to the detriment of the lives and rights of refugees and migrants. Similarly, biometrics companies were quick to jump on the bandwagon of requests for identification technologies without the need for human contact, in particular developing and promoting new facial recognition technologies.

Outsourcing

Instead of buying equipment or services from corporations, states increasingly outsource complete lines of work (or parts thereof) to private companies. This takes place in different areas of the border security and control field. Examples of such outsourced areas include the management of detention centres (sometimes including guards from private companies), deportations, and Frontex border surveillance. Last year, Malta hired three privately owned fishing trawlers to intercept migrant boats in the Mediterranean and force them back to Libya.

Outsourcing often results in large long-running contracts for private companies, but it comes with an extra price in terms of reducing the transparency, democratic oversight, and accountability of border work as the state relinquishes its role. Private companies operate from a logic of cutting costs and maximising profits, leading to sub-standard work practices, understaffing and excessive workloads, use of defective equipment and inadequate facilities, especially in working with vulnerable people, such as detained refugees and migrants.

Rise of new technologies and autonomous systems

The use of drones and other unmanned and autonomous systems for border security has become ever more important in recent years. Like Frontex with its €50 million contract for drone surveillance services, many European countries, as well as Australia and the US, have increased the use of drones for border security. Turkey and the US also introduced smart towers, provided by Aselsan (Turkey) and Andrul Industries (US), on their borders, using cameras, virtual reality systems, and radars to detect border crossings. To deter refugees and migrants, Greece started to use sound cannons on its land border with Turkey.

The use of armed autonomous weapon systems at borders against mixed migration crossing attempts has been proposed by industry, for example to Frontex, but so far has not become a reality.[2] However, the use of unarmed autonomous systems can also have serious consequences. Drone Wars UK points to “the risk that the use of drones, as a primarily military technology, in border control will contribute to the dehumanisation of those attempting to cross borders and increase the potential for human rights abuses.” The growing use of drones for surveillance in the Mediterranean, instead of crewed aircraft and vessels, has resulted in an evasion of humanitarian responsibilities to rescue migrant boats in distress. Drones have also been used to facilitate illegal pushbacks in the Balkans. And a study in the US concluded that the use of new surveillance technologies, including drones, at the US–Mexico border led to an increase in deaths, mainly by pushing refugees and migrants to take more dangerous routes.

The use of artificial intelligence, especially in the context of decision-making, for border security and control is still in its infancy, but already very controversial. The iBorderCtrl (Intelligent Portable Border Control System) project, funded by the EU with €4.5 million under the Horizon 2020 research programme, developed and tested an AI-based avatar interviewing system with a lie detector for border control. Even the consortium that ran the project had to admit that “some technologies are not covered by the existing legal framework, meaning that they could not be implemented without a democratic political decision establishing a legal basis.”

Border externalisation

The EU increasingly enlists third countries as outpost border guards, to stop migrants and refugees before they even reach its external borders. This practice involves dozens of non-EU countries, which are pressured in to acting according to the EU’s wishes using a carrotand-stick approach, with promises of better trade deals, visa liberalisation, and financial support, training and equipment as carrots, and threats of withholding development aid money as sticks. This has far-reaching consequences, not only for refugees and migrants— who encounter more obstacles and violence, have their human rights violated, and are forced to embark on more dangerous migration routes in the charge of often-abusive smugglers—but also for the population of many of these countries themselves. Development aid is diverted to border security and control. Internal stability and development are undermined, for example by disrupting local migration patterns which negatively impacts local economies based on facilitating migration. Authoritarian regimes, and in particular their military and security forces, are legitimised and strengthened.

This is not something that is unique to the EU. The US disburses billions of dollars and donates a wide array of equipment to increase border security capacities all over the world. This includes its ‘Frontera Sur’ programme to strengthen Mexico’s southern border with Guatemala.[3] Australia also cooperates with and funds neighbouring countries’ border security measures. An important part of this is its offshore processing system under which refugees and migrants arriving by boat are detained on Nauru and Papua New Guinea. In 2022, Australia will spend A$812 million ($607 million) on this system, almost A$3.4 million ($2.5 million) per person held.

All of these border externalisation policies and practices open up new business opportunities for military and security companies. This isn’t just a case of an industry that adapts to EU policies and takes the money. EU border externalisation is also used to stimulate and encourage more states and corporations to invest in border security and thereby foster “a hugely profitable export market for the European arms industry”.

EU instruments and budgets

EU spending on border security and control has been steadily increasing, most notably since the so-called “migration crisis” in 2015 when the expenditure curve steepened dramatically. Billions of euros have been channelled to strengthen border security and control at the EU level, in member states, and in third countries. Alongside existing instruments, the EU spent €6 billion on its 2016 migration deal with Turkey alone. At the end of June 2021, the European Commission proposed to spend another €3 billion to “support refugees in Turkey until 2024” and to “support Turkey to manage migration at its Eastern border”.

The EU increased the budget of Frontex to €5.6 billion under the new Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF 2021-2027), of which an unknown part is earmarked for purchasing or leasing equipment. The Integrated Border Management Fund, with a budget of €7.39 billion, consists of the Border Management and Visa Instrument and the Customs Control Equipment Instrument. It is meant to strengthen capacities of member states and to fund training, consultancy, equipment purchases, and so on. Compared to its predecessors (the External Borders Fund (2007-2013) and the Internal Security Fund – Borders (2014-2020) this again marks a huge budget increase. There are several other EU sources of funding for border security efforts in non-member states, including the Instrument for Pre-accession Assistance (IPA II), the new European Neighbourhood Instrument, the above-mentioned IcSP, and the off-budget European Peace Facility.

Big winners: the military and security industry

As pointed out above, the military and security industry is the main beneficiary of the EU’s militarised border policies. Large European arms companies such as Airbus (pan-European), Leonardo (Italy) and Thales (France) are among the most important companies in the European border security market. The same companies are major exporters of arms to the Middle East and North Africa, where they are deployed in wars and other types of armed conflict, as well as in civilian repression and human rights violations. All of these are push factors for mass forced displacement and migration, putting these companies in the unique position of doubly profiting from the same group of people: first by contributing to the drivers of their migration, then by providing the equipment and services to impede their journeys.

Other companies are big players in specific aspects of border security and control. The Spanish firm European Security Fencing was for a long time the sole provider of concertina razor wire that can be found on border walls and fences across Europe. Dutch shipbuilder Damen has provided border patrol vessels to many Mediterranean countries, including Turkey and Libya, as well as the UK. The French IT consultancy firm Sopra Steria is the prime contractor for the development and maintenance of EU’s biometric databases (EURODAC, SIS II, VIS), securing over half a billion euros worth of contracts since 2000, often as part of consortia.

In other countries, large sums of money are also at stake. In the US, the Customs and Border Patrol and Immigration and Customs Enforcement agencies issued over 100,000 contracts to private corporations between 2008 and 2020, with a total value of over $55 billion. Australia plans to spend billions on its Future Maritime Surveillance Capability, including an investment of up to A$1.3 billion ($970 million) in a new drone development programme. Saudi Arabia awarded a still-running contract, worth over $2 billion, to Airbus (then called EADS) in 2009 to provide a surveillance system for its borders. While billions flow to the arms industry as part of growing global military spending, aid organisations calculated in 2021 that the $5.5 billion needed to aid people facing or at risk of acute hunger is equivalent to less than 26 hours of the $1.9 trillion that countries spend each year on the military, also noting that “conflict is the biggest driver of global hunger“.

Mixed migration consequences

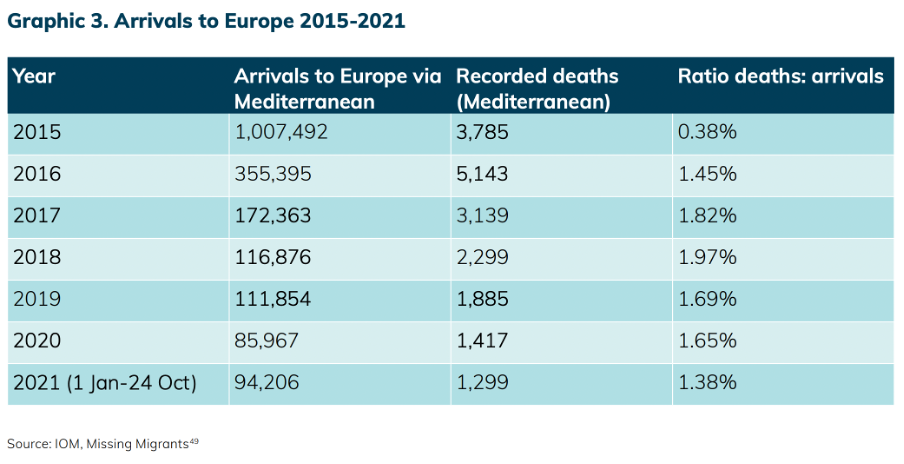

The consequences of Europe’s militarised border policies are devastating for refugees and migrants. According to a 2015 World Bank blog piece by Hein de Haas, border militarisation and increasing border controls “have mainly (1) diverted migration to other crossing points, made migrants more dependent on smuggling, and increased the costs and risks of crossing borders.” Regarding the first and third point, research shows that closing down a migration route doesn’t stop people from fleeing; most of the time it merely leads to a shifting of refugees and migrants to other, more dangerous routes. This often leads to a relatively higher number of deaths. The ratio of migrant deaths to arrivals to Europe via the Mediterranean grew to almost 2% in 2018, five times as high as in 2015. In 2019 and 2020 it remained high at 1.7%, and during the first half of 2021 rose sharply to 2.3% from 1 January to 1 July, but by the end of October the ratio was 1.38%.

The long and dangerous routes from the African mainland to Spain’s Canary Islands have seen a tenfold increase in the number of refugees and migrants trying to cross between 2019 and 2020, after years of very few such crossings taking place. This shift has partly been driven by increased border security between Morocco and Spain, and recent clampdowns against refugees and migrants by Morocco, spurred by deals with the EU. This underscores the point that shutting down routes does not stop migration, though it might result in lower numbers of arrivals and/or attempted crossings at certain points. Often, however, it diverts migration to more treacherous routes and in other instances leaves people on the move stuck, stranded or involuntarily immobile.

De Haas’ second point, that refugees and migrants become more dependent on smugglers, is an outcome that is apparently completely contrary to one of the stated goals of EU border policies: combating migrant smuggling. However, analysis points to the almost obvious: the actual goal is not so much combatting migrant smuggling as combatting irregular migration, where the so-called “war on migrant smuggling inherently pits authorities and states against people on the move—many of which are desperate to flee conflict or persecution and who are therefore protected under international law”.

If the EU stays on its course of increasing border security, of militarising and externalising its borders, its border and migration policies are bound to implode. Meanwhile, the EU’s “root causes approach” is characterised by flawed and incoherent policies. For example, it shifts development money to projects with the primary objective of reducing numbers of migrants instead of supporting development. And it ignores Europe’s own contribution to these causes by, for example, exporting arms to countries experiencing unrest and armed conflict and authoritarian regimes. As long as such issues aren’t tackled, the numbers of migrants and refugees trying to come to Europe won’t decrease, it will just mean that they are forced to take even deadlier routes to try to get to safety and will likely be contained somewhere along the way.

Even more so, the EU’s border externalisation policies are sowing the seeds for large numbers of refugees and migrants in the future. A UK parliamentary commission concluded that “the EU’s migration work in the Sahel and Sub-Saharan Africa risks exacerbating existing security problems, fuelling human rights abuses, and endorsing authoritarian regimes. Preventing local populations from crossing borders may help cut the numbers arriving in Europe in the short term, but in the long term it risks damaging economies and creating instability—which in itself can trigger displacement”. Or, as one unnamed EU official said: we are only “creating chaos in our own backyard” and that will eventually turn against us.

The EU’s militarised border policies have severe negative consequences for refugees and migrants—as well as for the populations of neighbouring countries outside Europe—and lay the foundation for even greater numbers of people to flee their homes in the future. In other words: they are not only inhumane, they are also untenable and counterproductive. In the end they serve no one’s interests, with the exception of the smugglers benefitting from an ever-increasing demand for their services and ability to charge higher prices to circumvent border controls, as well as the military and security industry that has been relentlessly pushing for these policies. The same industry that also earns money by fuelling the reasons people are forced to flee in the first place by providing arms and security equipment for wars, repression and human rights violations.

Another approach is both urgently needed and possible. This requires a rejection of an approach that treats migration primarily as a security threat and understanding it as a question of political will. Until Europe recognises its own role in provoking mass forced displacement and migration, shifts course, channels the massive investments in border security and refugees and migrant’s massive expenditure on smugglers into the creation of more productive and sustainable migration channels, countless more lives will be lost while the military and security industry and smugglers continue to reap the profits.

[1] EOS/EU ISS Task Force (2010) Concrete actions contributing to the foundation of the EU Internal Security Strategy as proposed by EOS. (Currently unavailable online, available from Ravenstone Consult by request.)

[2] Email exchanges between Frontex and industry representatives, as released under a Freedom of Information request to Frontex.

[3] Miller, T. (2019) Empire of Borders: The Expansion of the US Border around the World. London/New York: Verso.