The following story was originally compiled for the Mixed Migration Review 2020 and has been reproduced here for wider access through this website’s readership.[1]

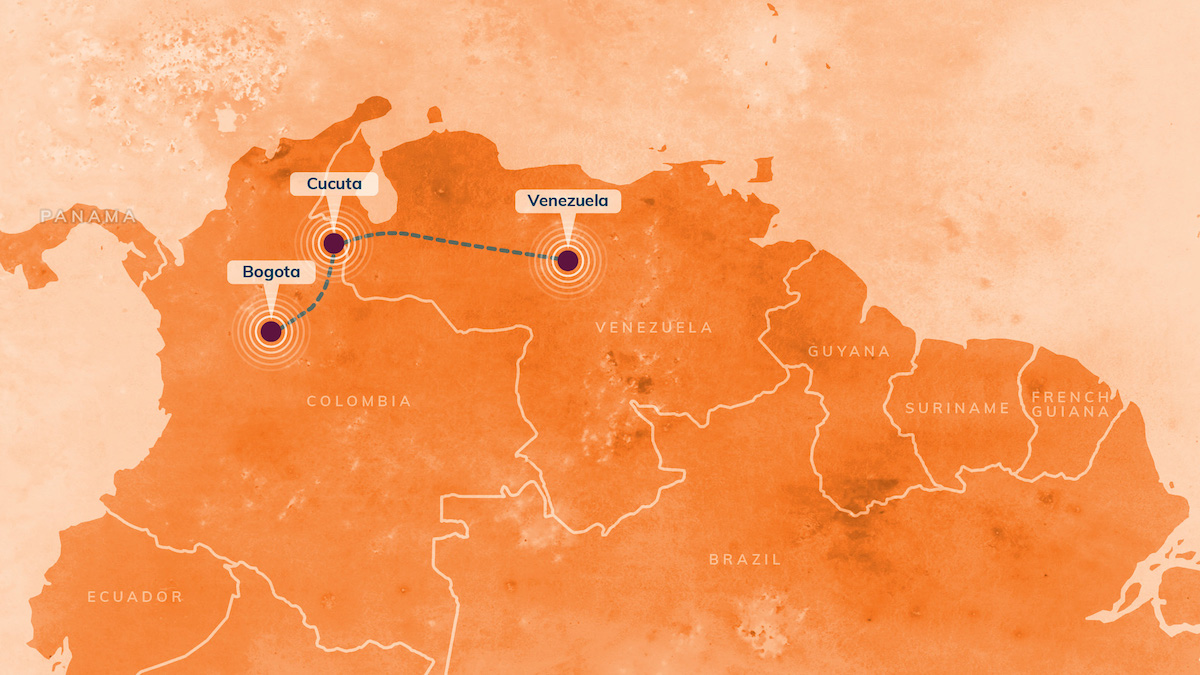

When armed youths entered the university, we decided it was time to leave Venezuela. My daughter called me from class as it happened. Over there you need to be in favour of the government, and I said in that moment that we needed to go. My son had already travelled to Colombia. The idea was for him to come and have a look, find a way to save money so that we could join him. But he couldn’t find a job, it wasn’t easy in Bogotá, and then he heard there were better opportunities in Peru, and he left. Then my daughter came to Colombia and once she was able to save enough for my ticket, I followed.

My son and daughter had no problems getting here, but I did. I arrived by bus to the border. I had to show my papers, I opened my purse, and I think that’s when they saw how much money I brought. I gave my passport to the officer, and all was normal, they let me in. But as I was walking, I saw a man coming towards me and there were other men nearby. And the young man tells me that I have to pay to enter Colombian territory. That hadn’t happened to my children, so I refused and kept walking. Ahead there was a Colombian officer who asked if I had paid to enter. I told him no, and he told me I couldn’t go on if I didn’t pay. They asked for the exact amount that I had in my purse. All I wanted was to meet my daughter, so I gave all the money to the young man and I could pass. I had nothing, and I didn’t know what to do, so I sat down, and some people showed compassion for my situation and helped me with my bus ticket to Cúcuta.

I’m a professional, I taught pre-school for twenty years in Venezuela and here I worked as a housemaid. It was one of many poorly paid jobs, hard work, some with a lot of exploitation, that I did before I got my residency permit. Some employers don’t even look at you or talk to you. Later I worked for a company where my employer harassed me. I had never been through something like that. I didn’t know that to do and I remember that I stayed still and couldn’t move, and I didn’t go back next day. I didn’t even pick up what they owed me.

After that, I found a job in a big company here in Chia and I was there until the pandemic. I was doing well, my boss was happy with my work. But with the pandemic and the quarantine, I was told to ask for vacation. And the day before starting my vacation I had to sign a new contract, but human resources said no, my passport had expired, so they couldn’t hire me. I knew that it was because I was Venezuelan, because while I was there, I could feel they looked at me differently.

This is not our country, and I don’t feel we’re welcome. We are foreigners here. Many people think we came here to take away their opportunities. I thought that because Venezuela gave many foreigners opportunities to move forward, that we would receive the same support. On the contrary, it has been hard to settle down. There are some people that are more humane, more kind. Others, not so much. But we also understand, there are many from Venezuela who came and didn’t come like us to make a living.

Before the pandemic, cooking was just an idea to make something extra but now it is our only livelihood. My daughter has studied cookery. She makes products based on wheat flour. Tequeños, cakes, what you call cheese sticks, potato and cheesecakes. It does not generate much money, especially now due to the pandemic, but at least we can sustain ourselves. Little by little, we have been working on it. Despite so many limitations, we keep going, from home and through social networks. We received information and support about the Minuto de Dios foundation, which provides support to Venezuelans in our situation. They are going to give her money for an oven and a countertop, and other little things she needs.

My dream is for my daughter to succeed with her business and finish college. If I have a dream right now, that would be it. And then to see my son again.

Migration is very hard. We left our country, we left our lives behind, my children had to interrupt their university studies, fleeing an economic crisis, to face another type of crisis. Xenophobia, discrimination, labour exploitation and sexual harassment. However, we continue to fight to get ahead, with honest work and taking advantage of our knowledge and skills. For now, we don’t have plans to move further. At least here we have a place to live and some calm. We don’t have much, but we have enough. I’d like to go back to my country when it gets better, but not for now.

[1] ‘Urban Voices’ presents seven stories from migrants and refugees living in cities drawn from detailed individual interviews conducted by MMC. They often illustrate the non-linear nature of so many migrant and refugee journeys – characterised by the twists and turns in many migrants’ erratic lives. They serve to offer evidence towards a new concept recently introduced in migration studies of circumstantial migration to describe how “migration trajectories and experiences unfold in unpredictable ways under the influence of micro-level context and coincidence.” [Carling, J. and Haugen (2020) Circumstantial migration: how Gambian journeys to China enrich migration theory. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies.] MMC did not record the names of respondents and all names in this ‘urban voices’ series are aliases.