The following story was originally compiled for the Mixed Migration Review 2020 and has been reproduced here for wider access through this website’s readership.[1]

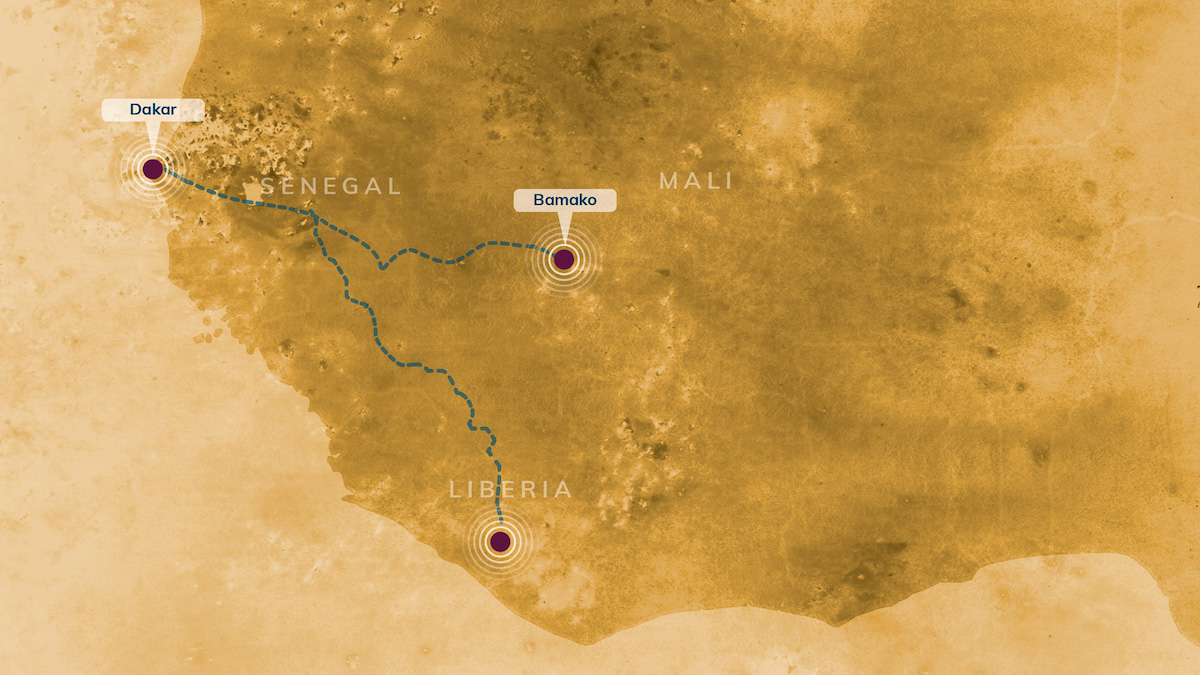

I have been in Bamako for about 10 or 11 months. I’m from Liberia and came to Mali via Dakar where I stayed for almost a year. Bamako was just a stepping-stone on my way north but I could not continue my journey, so I found myself here. I am doing my best to return to Dakar, but with the coronavirus it is not easy. Right now, I heard everywhere is open but I am waiting a little because I don’t have money. I left my home country due to many problems. Sometimes, in your family there are many problems. Sometimes, you don’t have money and you see other people leaving. So I decided to search for a place to make myself happy.

I am here with my three children. I gave birth to one here. I organised the travel all by myself, coming to Bamako by bus from Dakar. The travel was not difficult, the only difficulty is the people at the checkpoints who take some money from you. They will ask for 1,000 or 2,000 CFA francs ($1.8 or $3.6); it doesn’t matter if you have documents or not. Coming from Senegal to here was expensive. I paid for two places, one seat for 25,000 CFA francs ($ 45) and another for 30, 000 ($54). I was planning to go elsewhere but it did not work.

When I came here to Bamako, I went to IOM [the UN’s migration agency] and I explained that I planned to travel further north, but IOM said that this was difficult, so I did not go. The reason I remained here in Bamako was that I was pregnant when I wanted to return to Dakar. I had to wait to deliver the baby. I have one room with my children at a local shelter and, Alhamdulillah [praise be to God], we can live and eat here. We are many different migrants here; some are from Sierra Leone, others from Guinea-Conakry. The ones that came from my country, they left a long time ago. I have my papers, my children’s papers, and the things we came with from Dakar.

In Bamako, when you have your identity [papers], you can move around. When the police catch you, they want to know who you are, where you come from. When you show your ID, they understand, and they leave you alone. Many foreigners are here, but when they come, they don’t stay in Mali. They only use it as a transit point. When they have enough money, they move on to another country. Many foreigners think that this place is very hot! As soon as you have the money, you leave.

I feel safe in the name of Allah, but I am just tired now of being here. We came here, we heard a lot of stories. The people said: “Don’t let the children go out alone because there are some people…” You know everywhere in the world they have bad people and good people. So, we are very careful. But I do not experience discrimination. When I go to the mosque the people there are all God’s people, so they are my people too.

Here in Bamako, it is easy and cheap to get a place to sleep. People do things for Allah’s sake. It is a more traditional society. In Dakar, getting a place to sleep is very expensive. The people there, they behave like they are European. In Liberia, they behave like they are American, they are proud. Here, when you have problems, there are many organisations to help you. They look into your problem, they take care of you, they feed you and give you some clothes. When I was pregnant, the local shelter helped me, they took me to the hospital, and I received all the care I needed.

I had a problem with a man from Liberia. I met him in Dakar and we came to Bamako together. Here he started to bring problems, problems, problems. But he left and the problems are over now. I am taking care of my children and my baby. I have three girls. The local shelter is helping me to survive. I eat, I have a shelter but I don’t have money. I am not working. My children are not going to school since we came to this place. I don’t want to stay here. Bamako, Alhamdulillah, is good but the sun is too hot. I do not want to go somewhere else anymore, I want to return to Dakar. When I was in Senegal having money was easier. I see people that can help me. Here in Bamako it is difficult. I do not speak Bambara. There is no money. To go to Dakar, I need money and the boarders to be open. That is my problem.

[1] ‘Urban Voices’ presents seven stories from migrants and refugees living in cities drawn from detailed individual interviews conducted by MMC. They often illustrate the non-linear nature of so many migrant and refugee journeys – characterised by the twists and turns in many migrants’ erratic lives. They serve to offer evidence towards a new concept recently introduced in migration studies of circumstantial migration to describe how “migration trajectories and experiences unfold in unpredictable ways under the influence of micro-level context and coincidence.” [Carling, J. and Haugen (2020) Circumstantial migration: how Gambian journeys to China enrich migration theory. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies.] MMC did not record the names of respondents and all names in this ‘urban voices’ series are aliases.