The following stories were originally compiled for the Mixed Migration Review 2021 and have been reproduced here for wider access through this website’s readership.

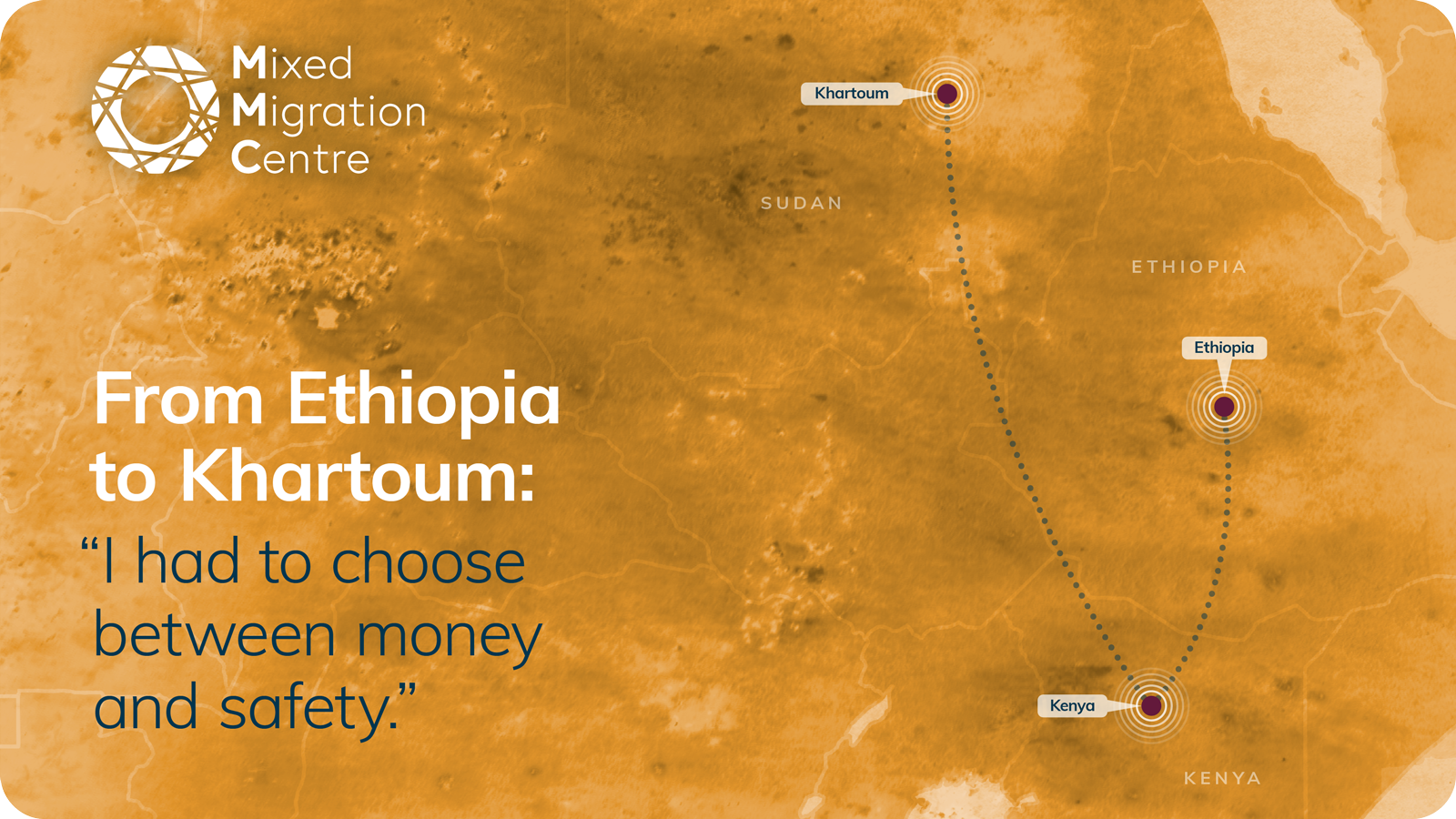

From Ethiopia to Khartoum: “I had to choose between money and safety.”

In Kenya, we coordinated as a community and planned to go back to Ethiopia to fight against the Tigrayans. We did not succeed, and after six years we decided to go to Sudan by plane.

I left Kenya for Sudan with two ideas in mind: coordinate with the opposition to combat the Ethiopian government or apply to UNHCR for refugee status and resettlement based on my political status. I went to Gedaref first when I arrived in Sudan, as I had heard that in the east in the camps it was better to get registered with UNHCR. They lost my file twice. How is it possible? After three years there I gave up on this and came to Khartoum in 2000.

In the beginning, I had no job, but later I created my own shop and started a family here, so I decided to stay. UNHCR eventually gave me refugee status and said they would update me about resettlement options later, but it never happened.

It has been very difficult for me to integrate in Sudan. I and my family are still considered outsiders. While some people are very hospitable, there are also very nasty people. We, as Ethiopians, have reached a point where discrimination is normal. For example, if a Sudanese were to steal from us, it doesn’t make sense to go to the police station. The police officers will take the side of the [Sudanese] nationals and you will end up in trouble. Integration is particularly difficult from an economic perspective as well. Sudanese might tolerate you, but they will not tolerate when you are successful and have a good business. I started my own shop, and often received humiliating comments from them. A Sudanese neighbour told me once I should leave the shop to him as I am an outsider and that he would do a better job. At some point it became dangerous, as I started receiving threats. Once, someone came with a knife and that’s when I decided I had to stop with the shop. My business was going well, and I had many customers, so this was a big disappointment for me.

I had to choose between money and safety. I got hired as a teacher, although I do not have the right qualifications for this. I am teaching history and family science. I feel safe and comfortable here, but I was making much more money with my shop. My earnings are not really enough to survive. If I need to, I can ask Ethiopian friends for help or a small gift, but I do it maybe once a year.

You always move because of rent. I live now in a compound together with four Ethiopian families. We have one room per family and share commodities. Sometimes a landlord forces you out by increasing the rent, which you cannot afford. This became much worse since the start of Covid. Before, landlords would tolerate it if you didn’t make enough money one month. They would note down your debt and you could pay it later. Now, if you can’t pay, you’re out, as everyone is scrambling to make ends meet. There is also a cooking gas shortage in Sudan, and it’s very difficult to find and expensive. Sometimes I see that a seller has it, but they tell me they won’t give it to me as I am not Sudanese.

I don’t feel very safe. The government changed after the revolution here in Sudan but there is still a risk for us Ethiopians to get arrested by the authorities. Khartoum is safer than other places in Sudan, though. In the East I think the risk to get arrested is bigger. I do feel safer in Khartoum right now than in Ethiopia. That’s why I don’t go back. Addis has not changed enough for me to go back.

Has my migration been successful? This is a very difficult question! Had I stayed in Ethiopia, I would have been a different person. I guess by migrating I have showed the world that the situation in Ethiopia is serious and we need help from the international community. This was the case in the ‘90s and is still the case now. I think by making other lives better, like in my job right now, my current situation is a success. I hope that with their education, the children will be ready to develop themselves after and to get a good life and job. I think education is the most important thing for becoming successful.

From Afghanistan to Indonesia: “We all have different journeys in life.”

We all thought we were going to die on the small, crowded boat I took from Malaysia to Indonesia. Our smugglers wanted to avoid a patrol boat but then got lost and we ran out of fuel and were stuck on the sea in pouring rain for 14 hours. People were baling out the water with baskets non-stop. The next day we were rescued by other smugglers. The whole trip cost $6,000, which I had to borrow.

First, I came to Bogor, the place with the biggest refugee community in Indonesia. I was teaching English in my room, but after a year I realized there was no other opportunity for me, economically and socially, so I left for Jakarta in 2014 and have stayed here since then. I never thought I would be here for eight years. I always hoped to be resettled in Australia or go there with smugglers, but boat arrivals were forbidden, and I never got the resettlement.

I haven’t made a family here and I live alone. I don’t want to start a serious relationship when I am still a refugee. I just want to be resettled first and start a new life with more economic and social stability. In Jakarta, there are opportunities to make friends, build my social network and make a living. I found a lot of new friends from other countries here as well. With what is happening in Afghanistan, people usually ask me about the news. Talking to them really helps a lot. They show me that they care for me and my people, even before the Taliban’s takeover.

Even though refugees are not allowed to work in Indonesia, opportunities come along. If you are active in looking for jobs, you will be able to make a living. I started multiple careers here, as an English teacher, gym trainer, model, and videographer. I started by talking to strangers at the mall. I told them that I was a teacher, and I could teach mathematics and English. Indonesian people are very friendly, and I could find some students that way.

Videography is my favourite thing to do of my different jobs. Videography is like writing. The feeling I have with my camera is like the feeling a writer has with their pen. You create something, you make a video, you share your thoughts and feelings. However I am not a professional videographer yet and I still have a lot to learn.

The lesson learned here is to not be scared. There were of course times when I thought it was impossible to continue my life, and there were times when I had to make risky decisions. For example, coming to Jakarta was very risky because the cost of living is much higher than Bogor, and what if I could not find a job? But every time I met a challenge, I told myself, “Don’t be afraid. Take the risks. The solution will be on the way.”

It takes a lot of courage, even to talk to people here. The good thing is the Indonesian people I met are very friendly and honest. For example, the manager of the gym in my building saw me running outside and let me use the gym for free. Back in Iran, I was not very social because most Iranian people discriminate against Afghans.

I wish I could encourage more people who are in a similar situation to mine. The problem is that living the life of a refugee for such a long time takes the courage from many people. I have talked to many refugees from Afghanistan here, but it seems like they no longer care about their lives. The situation drains them out, they don’t see the point of doing anything.

I think we need to motivate ourselves no matter what situation we are in. There was a time I had nothing to do as well. I stayed at home for a few months, so I borrowed a guitar from a friend and started to practice the guitar around six to eight hours a day in my room. I don’t think other refugees are lazy, they just lost their hope.

We all have different journeys in life. Sometimes, the journey is tough and not likeable, but at the end of the day, there will be a solution that is worth all the waiting and effort.

From Cameroon to Mali: “I couldn’t have dreamed of anything better.”

First, FN and I went to Niger, where we joined the Aigles d’Agadez football club to earn a bit of money before heading on to Algeria after a year. A few months later we went on to Morocco. But in 2005 they were chasing down migrants there, acting as Europe’s policemen. We lived in the forest in flimsy huts the police kept destroying. To eat, we would rummage through garbage bins or beg. Then they sent us back to Algeria, from where we were also deported.

When Algeria deports people, it puts them in prison. If you are caught in Algiers, they take you from town to town and hold you in prisons until quotas are filled, at which point you are taken to the next town. The last one [before the border] is Tamanrasset, where there is a large refoulement centre where people are held for up to two or three weeks. It’s more of an open-air jail. There are no mattresses, you sleep on cardboard boxes, the showers are mixed with the toilets, women and men

are not separated. You are given two loaves of bread and a litre of milk for two days. Then they put you in closed trucks, as if you were animals in cages, and take you to the border. When they stop, it’s only for a minute or two to pee. During one stop, FN fell asleep and we almost left him behind. I will never forget these things.

We were taken to Tinzawaten, a desert border settlement in the far northeast of Mali. From there, we had to beg smugglers to take us to Kidal because we had no money. It is only thanks to God that we did not die on that journey. From Kidal, we travelled to Gao and then on to Bamako. Even there it was not easy because we had no contacts.

For a while I lived in a “ghetto” in Bamako. This was an abandoned building with about eight rooms and there was no water or electricity. Migrants of all nationalities who had been deported were living there. There were eight, ten or fifteen people per room and we split the rent. People got sick and some died without any support. There were a lot of police raids. The neighbours used to call the police, calling us criminals.

There was no one to speak on our behalf. So in November 2006 we decided to form an organisation to assist deported Central Africans living in Mali, called ARACEM. People were suspicious of us at first and thought this project was just a way to make money to migrate. But we built up trust and found partners. Today ARACEM is a reception centre that takes care of people, whether they are in transit or returning. The assistance we provide is protection in the broadest sense. It includes reception, accommodation, food, health, etc. This is the most positive thing I have had in my life.

I have always remained a footballer at heart. Ten years ago I even created a football team here in Bamako, to give young people a chance, because I said to myself if I didn’t have this chance, why not try to help these young people because today there are opportunities. It’s true that I couldn’t achieve my own dream, but I would like to help other young people to achieve theirs. The team didn’t work out in the end because there were too many bad people. But two years ago, I finally created a club in Cameroon and it’s still going well. It’s very important to me to give a chance to young people who want to succeed.

As for me, I now have a family with children who go to school. I couldn’t have dreamed of anything better.

Giving advice is complicated because if you advise a young person to stay put, you have to give them solutions to make a life for themselves. I would say, be determined in what you do because when you have objectives and you find yourself facing obstacles, you must not give up. Know that you can make your life everywhere, not only in Europe.

From Ethiopia to Somalia: “Now I am the manager of a barber shop”

I came alone to Bossaso and my family stayed in Gondar. First, I took a bus to Jijiga [the capital of Ethiopia’s Somali Regional State] and then a truck to Wajaale [a town on the Ethiopia Somaliland border]. In Ethiopia, the travel was quite stable but after I crossed the border to Somalia I started walking and sometimes used an overcrowded truck with a lot of other migrants. It was very dangerous and risky. I walked days from Garowe to Gardo, and so many days from Gardo to Bossaso. I had no water, no food. It was very expensive for me because I didn’t have enough money.

I came here with no money. My plan was to cross the sea to Yemen and then travel to Saudi Arabia. The first month after my arrival in this city was not good. I had no one to help me, I had no shelter and no money, even for food. I was living on the side of the road and was begging to get something to eat from the local people. It was very rough and I was very desperate. I had very many challenges, but I was receiving a little assistance from my fellow migrants. I did not know the language also and had no friends or family to help me.

Fortunately, and unfortunately at the same time, I failed to get money [for the journey to Yemen] from my family and friends because of the economic and political problems back home. I tried to get work, but I did not get it at first. One day, I walked to the city and I found someone from Gondar who told me that one of my relatives was in Bossaso. That man was working in a barber shop owned by a Somali man. I told him that I was looking for a job and fortunately because I had a barber shop back home I was very good at it. He told me to join them and eventually I become a permanent employee. I was planning to get some money that could get me to Saudi Arabia, but after a month of work I realised that this job could sustain both me and my family back home, so I decided not to go anywhere else and stayed here to feed my family.

Now I live with the friends I work with in the barber shop. They come from same city as me; that’s why I live with them. My living conditions are very good because I receive a monthly salary. I have a good number of clients and people especially request my services and they prefer me to cut their hair. Now I am the manager of the barber shop. I work from morning to midnight, and I receive a good salary from it.

The local people are good and friendly people, and I have reliable security in the city. I have friends from all sectors of society because I deal with them all time, from elders, to police, government officials, business people and ordinary people. I feel secure here. People here are very flexible and very helpful. If I have a problem, I ask them to help and they help me all the time. They are very open with no discrimination. I’ve survived so far with no [outside] assistance. But now I work and I earn money from my work, so I’m able to sustain myself.

My dream is to bring my family here because of the war in Ethiopia. I am planning to bring them here and to start on my own business. My dream is to start my own barber shop here and to open other branches in this city and in the other city in this region.

When I first got here, I thought that I would end up with nothing and was worrying about my future, but now I am successful, and I’d like to tell my fellow migrants not to make that risky journey to Saudi Arabia, but to start finding jobs here. Here they can get jobs. They should not give up looking for jobs, they should be patient.

From Venezuela to Colombia: “If a door closes, a window opens”

I originally planned to go to Peru, because it was better-off economically. People would tell me that over there I could make good money and it was better for sending remittances to your family. But I didn’t have enough resources to get to Peru, or acquaintances there. I was completely alone. Then one of my neighbours migrated to Colombia and he helped me to come here to Barranquilla.

I migrated by myself, travelling all the way by bus or car. My first time crossing the border into Colombia I was very afraid, because I didn’t know anybody. In that moment, your life depends on a bunch of people you don’t know. They can do whatever they want with you, because nobody notices. That was the most horrible experience of my life.

I met someone here, who became my partner, and after a year we began planning to go to Peru, to where my father had moved in the meantime. But as we were organising the trip, I discovered I was pregnant, so we decided to stay.

In the beginning, my life in Colombia was very hard. During my first months here, I was very depressed. I cried every day because I had left my son behind in Venezuela. The only job I could get, making juice in a fruit store, paid just 8,000 Colombian pesos ($2) for half a day’s work. I knew that at that rate I wasn’t going to make it, and at that time you wouldn’t hear of organisations that were helping migrants.

Venezuelan diplomas are worthless here. I’ve had plenty of work, as a waitress, cleaning houses and making desserts for a restaurant, but although I sent my CV everywhere, I found no formal job. Potential employers always ask me if I was Venezuelan. Before I got my permit, they would ask me if I had my paperwork and since my passport had expired, they would never call me back. Even now that I am regular, I see no real difference with regard to finding a job. In terms of healthcare, it is easier, they treat you better when you go to a hospital, like a citizen, you notice the difference. But for work it hasn’t helped me much.

So when one organisation [that was offering a few weeks’ work conducting interviews] asked for all my documents, I had a feeling that this was going to be my great opportunity. Every night I prayed and when I spoke with my mum, I remember I told her: “Mum, if I don’t get this job, I’m never going to have a chance in life.” When I got the job, researching urban migration, it was more than just an opportunity: it was the chance to believe in myself again, to feel useful again.

Barranquilla has given me a lot. It gave me my family, I have my home here. There are also things here that we could not access in Venezuela: here, with a little money, you can go to the park and buy an ice cream; you can’t do that there. Even if you don’t have health insurance, if it’s an emergency, they will assist you. If I ever want to go back to Venezuela, it will be very difficult because I feel that I could not adapt anymore.

I have many dreams right now. I would like a job, a formal job. I want it with all my heart because my husband didn’t study and he doesn’t have many opportunities, he is a recycler. I feel that I at least have a little more knowledge, but I have the disadvantage that I am Venezuelan. I feel that if I had a formal job, with all my benefits, I could progress, we could progress as a family.

I don’t consider my migration as a failure because look at all the beautiful things I have: my family, my daughter, we have a roof over our heads, we have food. I have been able to support my family back home. Despite everything, I also feel like I have been able to integrate into society. The only thing I would need to be completely happy is to have my mum and my son here with me.

I don’t allow feelings of anguish and failure to overcome me. If you feel that you are here for a goal, you can do it. If a door closes, a window opens. It’s all about searching and searching.