In recent years the role of human smugglers has become central to the economy and dynamics of mixed migration – the relatively new phenomenon that sees refugees, asylum seekers and economic migrants moving together under similar conditions and facing similar risks.

Smugglers are widely regarded as unscrupulous and exploitative, taking advantage of irregular migrants’ desperation to move by charging high fees and sending their clients out on over crowded, unfit boats to cross dangerous seas. But recent findings from data gathered in the Horn and North Africa indicate this is only part of the story, and reveal two further alarming aspects of the migrant’s experience.

Firstly, that the smugglers are directly responsible for the high number of violations perpetrated upon migrants during their journey, and second, that certain state officials are also closely implicated. This article argues that unless the tight, criminal relationship between certain state officials (including border guards, police, military, and immigration officials) and smugglers is recognized, national and international efforts to address irregular migration and reduce vulnerabilities of migrants will be fruitless.

The new data from RMMS’s 4Mi project based on over 2,500 interviews with migrants in transit and destination countries within and far beyond the Horn of Africa, as well as 111 interviews with smugglers, confirms findings from other less publicized studies1 that the greatest risks facing most migrants on the move come from their proximity to their smugglers and the state officials they encounter en route. Migrant and refugees violations are not a monopoly of certain state officials on the African continent – a new Amnesty International report also cites Italian police abuse of migrants under pressure from EU for Italy to ‘get tough’ on migrants.

Interviews were conducted with smugglers primarily taking Ethiopians, Eritreans and Somalis from the Horn of Africa along the northern route (to Europe), the eastern route (to Yemen and Saudi Arabia) and the southern route (to the Republic of South Africa).

4Mi data finds that on average 75 per cent of migrants use smugglers for the majority of their journey. Going south to South Africa up to 95 per cent of irregular migrants use smugglers. Such is the demand for their services that 87 per cent of migrants interviewed stated that they themselves or friends and relatives voluntarily made the initial contact with smugglers. Only 10 per cent indicated that they were approached by smugglers offering their services. Smugglers are deeply entrenched in migrant’s social networks, local communities and all migrants interviewed in the previously cited MEDMIG report stated they used services of migrants for one part of journey or entire journey.

Such a bullish, high-demand and lucrative market may explain why both smugglers and the state officials who have contact with smuggled migrants, act so unscrupulously – careless of damaging their own ‘business model’ and fearless of punishment. From their perspective there is a seemingly unending stream of migrants and refugees who pay smugglers however badly they are treated. From the migrants and refugee perspective, smugglers are also revered as saviours, delivering them to a safer place and a better life. Disconcertingly, as a new publication found, it is often criminals who help the most desperate, when the international system turns them away.

This, however, is not surprising. A recent MEDMIG report working to understanding the dynamics and drivers of Mediterranean migration in 2015 interviewed migrants and smugglers and found that smugglers played two important functions; first, helping migrants to escape danger, or persecution at home / in transit countries and secondly, helping migrants to by-pass official borders (noting that one in ten migrants had tried but failed to find alternative legal means to enter EU etc.

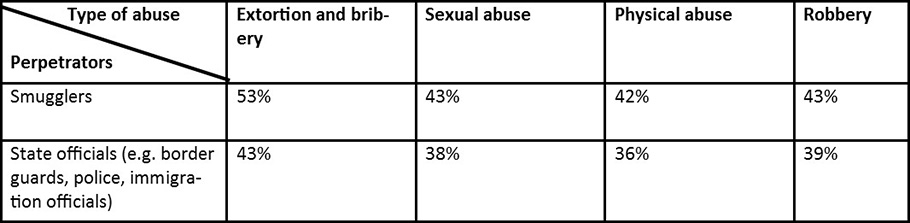

The range of violations reported by migrants through 4Mi and by interviewed ‘observers’ in migrant transit locations include robbery, deception, sexual assault, physical assault, disappearances (sometimes trafficking), holding people against their will, extortion, detention and even death (normally through extreme negligence resulting in vehicle accidents and dehydration or starvation due to a lack of access to water and food, rather than deliberate murder). The alarming findings of the 4Mi data gathering over the last two years indicates that smugglers are the major perpetrators of all these violations but that collectively different state officials are also actively perpetrating violations against migrants. A selection of these findings are illustrated in the table below.

Type of abuse and most common perpetrators according to migrants who witnessed or experienced abuse (n = 2,547)

Source: Mixed Migration Monitoring Mechanism Initiative (4Mi); http://4mi.regionalmms.org/

The fact that both groups – smugglers and state officials – often witness each other’s’ abuse of migrants binds them in mutually defending a joint enterprise of criminality that is essential to the robustness and resilience of the smuggling economy.

Importantly, the migrants themselves are the third element of the triangle or triumvirate of interested parties in this migration compact. Refugees and migrant using smugglers are victims of egregious violations and yet willing, paying, and surprisingly knowledgeable participants. Even if their ‘willingness’ is only a reflection of their absence of choice of alternatives. In research with Ethiopian migrants in 2014 it was found that a high percentage (80 per cent) of those intending to migrate were very aware of abuses they would encounter when in the hands of smugglers. Not only are they aware of the risk of serious abuses, they are also prepared tolerate these. Specifically, for example, 44 per cent claimed they would tolerate degrading treatment and verbal abuse and 33 per cent would tolerate extortion and robbery as a necessary evil of being successfully smuggled.

Additionally, a recent RMMS briefing paper highlighted the extent of migrant exposure to social networking and extensive use of smart phone communication with successful migrants and the diaspora, which means that many, if not most migrants and refuges have some knowledge of what to expect from their smuggler and the journey they are embarking upon. And still they come – without legal ways to move they are forced to make deals with the smugglers they know will expose them to human rights violations and possibly death. 4Mi data suggests that at a conservative estimate around 2,000 migrants and refugees died in remote desert crossings towards Europe in the last two years (especially in Sudan and Libya), while IOM record the number drowned in the Mediterranean is almost 8,000 during the same period. The relatively small number of migrants interviewed in the 4Mi project (2,547) compared to the number of migrants who have transited through the Sahara desert over the past two years (possibly hundreds of thousands) suggests that the actual number of migrants dying before they reach the shores of Egypt and Libya, is likely much higher than the number of migrants dying in the Mediterranean.

The high profits both smugglers and certain state officials extract from the migrant economy further cements the smuggler/state official relationship making it particularly resistant to national and international efforts to implement rule of law and improve protection for migrants on the move. The fact that migrants perceive the resulting benefits of successful international smuggling as worth the financial cost and personal hardship (including the risk of death) means the model will be even harder to challenge.

These are the sober realities that policy makers and implementers of recent grants created to mitigate mass mixed migration cannot avoid. The European Union Trust Fund, The EU Better Migration Management, the Valletta Process and the Khartoum Process are all new instruments generating hundreds of millions of dollars and multiple interventions that are likely to achieve little change unless the migration compact between smuggler, state officials and migrants and refugees themselves is addressed, in addition to the deeper triggers of out migration which will continue drive more people out of their country to seek better protection and opportunities elsewhere.

1 Some examples IOM 2009 In Pursuit of the Southern Dream, RMMS 2013 Migrant Smuggling in the Horn of Africa and Yemen, RMMS 2012 Desperate Choices, Human Rights Watch ‘I Wanted To Lie Down and Die’.

Note: This article originally appeared on the RMMS Horn of Africa website.