In 2016, a record number of migrants and asylum seekers arrived in Italy along the so-called Central Mediterranean route: 181,436 individuals arrived in Italy, an 18 per cent increase compared to 2015. But, contrary to an increasing number of articles and commentary, this migration flow is completely unrelated to what happened on the Eastern Mediterranean route – the Greek side. This feature article aims to provide some additional analysis on this record number and debunks the fiction that migration has moved from the Eastern to the Central route.

Misconceptions

Amidst the unprecedented focus on and coverage of migration flows to Europe, the record number of arrivals in Italy received substantial media coverage. Nevertheless, despite this extensive coverage, in many articles and commentaries on this record number of arrivals, two common misconceptions prevail: that the increased usage of the Central Mediterranean route to Italy is related to a shift away from the Eastern Mediterranean route, and that this shift is in turn related to the EU-Turkey deal. An upcoming RMMS feature article will discuss this latter misconception, this article will focus on the former.

The EU-Turkey deal shifting flows from Greece to Italy?

Especially in the early months after signing the EU-Turkey deal, many observers predicted the deal would lead to shifting migration flows, with more migrants and asylum seekers once again using the Central instead of the Eastern Mediterranean route to Europe. While a plausible expectation at the time – since migration flows often divert in response to closed borders and increased migration controls – actual data shows this shift has not happened to date. Nevertheless, the connection is still being made, both in shorter news articles and in longer opinion pieces, published months after signing the EU-Turkey deal. A few of the examples:

“Many people seeking [..] have been attempting to reach Italy from Libya after a closure in effect to migrants of other land routes and over the Mediterranean.”

“The deal is directly responsible for refugees travelling to North Africa and taking the far more dangerous route across the Mediterranean Sea.”

“[..] the closure of the Turkish route has pushed migrants and refugees further east into the far more professional and violent networks facilitating sea crossings from Egypt and Libya. The result is that this year has just become the deadliest on record for sea crossings in the Mediterranean”.

“There is a clear connection between the EU-Turkey deal, as well as the closure of the Balkan route, and the rise in arrivals from Libya and Egypt”.

Dismantling the myth: A closer look at the data

If there would have been a shift in the routes, whether an absolute or a partial one, this should be visible in the data from Italy in at least two ways: we should see a quantitative increase along the Central route similar or coming close to the decrease along the Eastern route, and we should see an increase in the number of migrants/asylum seekers from those specific countries where we see a decrease on the Eastern route.

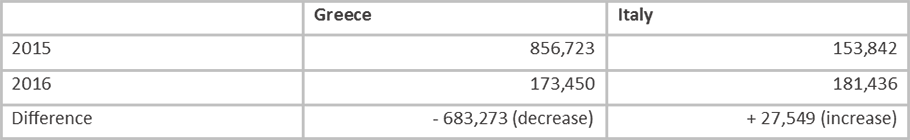

First of all, the table below shows the total decrease and increase in arrivals along the Eastern (Greece) and Central (Italy) routes.

Source: http://data.unhcr.org/mediterranean/regional.php

The data show that there has not been an absolute shift of migration flows, but at most a very partial one, since the decrease along the Eastern route is 24 times the increase along the Central route.

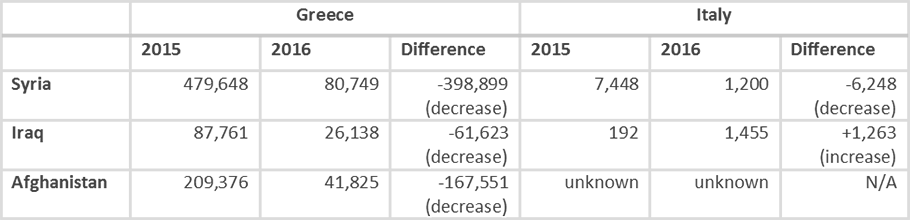

However, a closer look at the nationality of migrants arriving in Italy will reveal whether there has indeed been a partial shift, as assumed in the articles referenced above. The top 3 countries of origin of those arriving along the Eastern route in 2015 were Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan. In 2016, none of these countries features in the top-10 of those arriving in Italy. Although this is already a strong indication there has been no shift, the persistence of the ‘shifting flows myth’ deserves an even closer look at the data, to analyse whether at least there has been a minor shift. The table below compares the number of arrivals from these 3 countries in Greece and Italy in 2015 and 2016.

Source: http://data.unhcr.org/mediterranean/regional.php

The data above clearly shows, that even though a record number of migrants and asylum seekers arrived in Italy in 2016, there is no relation with reduced movement along the Eastern route from Turkey into Greece. The numbers of Iraqis arriving in Italy only marginally increased, while the number of Syrians arriving in Italy in 2016 even decreased by almost 84 per cent.

Profile of migrants along the Central versus the Eastern route

Finally, the profile of those arriving in Italy is also markedly different from the profile of those arriving in Greece in 2015. While asylum seekers arriving along the Eastern route originate from countries in conflict, mainly Syria and Iraq, the majority arriving in Italy (over 63 per cent) comes from West African and North African countries where these is no war. Migrants from countries like Gambia, Senegal, Nigeria, Ghana, Guinea, Cameroon and Sierra Leone accounted for the strongest relative increases in 2016 compared to 2015. Many of them are seeking better economic opportunities in Europe. Although the prospects for a quick resolution of the conflicts in Iraq, Syria and Afghanistan may be bleak, this flow may reduce once the wars are over. Migration from those sub-Sahara African countries, where there is not necessarily an ongoing conflict, is there to stay. Contrary to the Eastern route, migration along the Central route to Italy has also been relatively stable in recent years: the number of arrivals decreased with 9.5 per cent between 2014 and 2015, and then increased again with 18 per cent in 2016, very different from the massive fluctuation in arrivals in Greece in recent years. With continuing and rapid economic development, migration is most likely to increase in the coming decades, since more and more potential migrants will acquire the necessary resources and aspirations to migrate.

EU countries focusing on the Central route again

Contrary to the population arriving in Greece throughout 2015, the asylum claims of most of those (with the exception of the Eritreans and to a lesser extent Sudanese and Somalis) arriving in Italy are likely to fail. However, failed asylum seekers are difficult to deport. Aware of these difficulties and realizing this is a different migration flow, European countries are increasingly looking at the Central Mediterranean route again. In recent weeks, Germany proposed to cut development aid to countries that refuse rejected asylum seekers. The Maltese presidency, among others, is pushing for a deal with Libya to curb migrant flows that would be loosely modelled on the EU-Turkey agreement. And Italy is brokering an agreement on fighting irregular migration through Libya and re-opened its embassy in Tripoli (the first Western country to do so in two years), which will be the principal coordination centre for joint efforts to fight irregular migration and human trafficking.

The persistence of myths: strong passions and limited (use of) evidence?

While European countries have once again turned their eye to the Central Mediterranean, after the strong decrease in arrivals in Greece, this migration flow is completely unrelated to what happened on the Eastern Mediterranean route. There may be several reasons why the ‘shifting flows myth’ still persists. Some observers may, despite the facts, still truly believe that flows have shifted from the Eastern route to the Central route. Journalists, under time pressure to produce articles, may copy each other and do not have the time to properly check the data. Finally, some who are opposed to the EU-Turkey deal, may deliberately argue that the flows have merely shifted to Italy, to criticize the agreement and ‘prove’ it has done nothing but diverting the flows, pushing migrants in the hands of unscrupulous smugglers operating along the Libyan coast and forcing migrants to embark on much longer, more dangerous sea journeys. As Paul Collier noted in this book ‘Exodus’ for “choices concerning migration policy, limited evidence collides with strong passions”. However, in an increasingly polarized debate around migration, it remains important to keep the facts straight, especially since the evidence, as shown in this article, is easily available.

Note: This article originally appeared on the RMMS Horn of Africa website.