While the total number of migrants and refugees arriving in Italy in 2016 hit a record, the number of Eritrean arrivals in Italy decreased significantly in the past year. This articles explores the possible explanations for this sudden drop in Eritrean arrivals in Europe.

Decreasing number of Eritrean arrivals in Italy

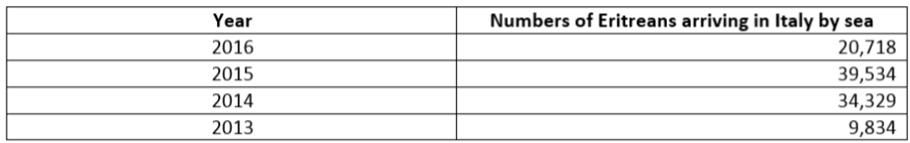

Since 2013, the major destination for Eritreans in onward migration, leaving the Horn of Africa region, has been Europe. The table below shows the number of Eritreans arriving in Italy between 2013 and 2016.

Source: http://data.unhcr.org/mediterranean/regional.php.

Eritreans were the single largest group of migrants and refugees entering by sea Italy in 2015, totaling 25 per cent of all arrivals in Italy. However, the number of Eritreans travelling along the Central Mediterranean route into Italy significantly decreased in 2016, almost 50% compared to 2015. In contrast, overall arrivals in Italy hit a record number of over 181,000 persons. This suggests the decrease in the number of Eritreans arriving in Italy is most likely not directly related to the situation in Libya (e.g. Eritreans getting stuck in Libya), on the Mediterranean Sea, or in Italy, since West Africans, from Northern Libya onwards, are using the same route as Eritreans to get to Europe.

Entering Europe through other channels?

In a recent study, the Overseas Development Institute concluded that while the overall number of people arriving in Europe by sea through ‘overt’ routes decreased, tighter border controls have rerouted refugees and migrants towards alternative ‘covert’ routes. If Eritreans were to arrive in Europe via other, covert means, the number seeking asylum would be higher than the number registering in Italy as new arrivals. However, the number of asylum applications by Eritreans in Europe between 2013 and 2015, has consistently been similar to the number of arrivals in Italy: 14,665 in 2013; 36,990 in 2014; 33,095 in 2015 and 22,545 in the first three quarters of 2016 (note that not all that arrive in a given year will get processed in that same year due to asylum decision processing delays). It is therefore assumed that most Eritreans arriving in Europe seek asylum on arrival, especially since recognition rates for Eritrean asylum seekers have been around 90 per cent in 2014 and 2015. The conclusion is that there are not a lot more Eritreans arriving in Europe by other means than by sea in Italy and very few are failing to apply for asylum.

Eritreans along other migration routes out of the Horn of Africa

Are Eritreans increasingly opting for other destinations than Europe? The Northern route, into Sudan and Egypt, via Sinai into Israel used to be a major route for Eritreans. However, this route has been severely restricted as of mid-2012, when Israel sealed the border with Egypt with a wall. The wall has been almost entirely successful in keeping irregular migrants out and hardly any Eritreans have entered Israel since then.

The Eastern route (into Yemen to Saudi Arabia and other Gulf States) is the most documented route and the most popular for migrants from the Horn and Eastern Africa. However, among the more than 800,000 migrants and refugees from the Horn of Africa who are estimated to have arrived in Yemen between 2006 and 2016, the number of Eritreans has been negligible. Almost all of those arrivals are Ethiopians and Somalis.

The Southern route runs down the eastern corridor of Africa towards South Africa. However, again Eritreans do not feature prominently within this flow. Virtually all irregular arrivals from the Horn of Africa apply for asylum in South Africa, which means the South African asylum statistics provide a good picture of the total number of arrivals. Between 2012 and 2014, only 112 Eritreans applied for asylum in South Africa.

Stuck in refugee camps in the region?

Generally, once they have fled their country, it is assumed most Eritreans initially apply for refugee status in Ethiopia’s and Sudan’s refugee camps. However, as Human Rights Watch noted in 2016, the Eritrean camp population generally remains more or less stable. This means that the numbers leaving Eritrea and those leaving the camps and engaging in onward migration are approximately the same. A study by the Migration Policy Institute recently concluded that Eritreans are particularly reluctant to live in refugee camps and frequently use smugglers to practice onward movement. In a recent study on onward movement by refugees in Ethiopia, it was also concluded that almost 40 per cent of Eritrean refugees leave the camps in Ethiopia within the first 3 months of arrival, and 80 per cent leave within the first year. Even though the registered Eritrean refugee population in Ethiopia increased by approximately 7,000 between 2015 and 2016 (while the Eritrean refugee population in Sudan seemed to have decreased), this increase in Ethiopia cannot fully account for the decrease in arrivals in Italy.

Eritrean communities in urban centres throughout the region and beyond

Some Eritreans do not register in camps but settle in Eritrean communities in cities such as Addis Ababa, Nairobi, Kampala, Khartoum, Cairo and Tripoli. Some as undocumented and unofficial migrants, others as urban refugees (either registered in that city or previously in a refugee camp in the same country or in another country). In a recent study, it was estimated 15,000 Eritrean refugees reside in Addis Ababa. It could be assumed there are many more who are not registered. According to UNHCR, over 81,000 Eritrean refugees previously registered as living in the camps are believed to have spontaneously settled in Ethiopia.

Similarly, there is a large community of Eritreans in the Sudanese capital Khartoum, who either live there, but have never registered as refugees, or who use Khartoum as a transit point along their migration towards Europe. However, exact numbers are unknown. In 2010, UNCHR estimated there were 40,000 Eritreans living in Khartoum.

Finally, several articles in 2016 reported on the increasing of the number of Eritreans in Egypt (Cairo), According to UNHCR figures, there are 6,079 registered refugees from Eritrea in Egypt, while 662 Eritreans are reported to be detained by Egyptian authorities. Although precise numbers are unknown, it could be assumed that a substantial number of Eritreans leaving their country in 2016 have settled in urban centres along the migration routes within and out of the region.

Intercepted and deported in Sudan and Egypt

In an effort to stem the migration flows to Europe, there have been increasing reports throughout 2016 about Eritreans being intercepted, detained and sometimes deported back to Eritrea by Sudanese and Egyptian security forces. Egyptian border patrol and coast guard reportedly stopped 12,192 persons from irregularly entering or leaving the country in 2016. Although the number of Eritreans among those is unknown, Eritreans have increasingly been using Egypt instead of Libya to get to Europe. Moreover, over the course of 2016, Sudan has intercepted, rounded up and deported hundreds of Eritreans. According to Human Rights Watch, these deportations took place with regularity. The exact scale is unknown, since Sudanese authorities do not always allow the UNHCR access to these migrants prior to deportation. Clearly, these deportations could be one of the major reasons for the lower number of Eritreans arriving in Italy in 2016, either as a deterrent for Eritreans to enter Sudan, or in preventing those intending to reach Europe from doing so.

Missing migrants, deaths, disappearance

Sadly, not all migrants and refugees who leave Eritrea make it to their destination. In 2016 alone, a tragic record number of 5,079 migrant deathsoccurred on the Mediterranean, including a large number of Eritreans victims. Additionally, 4Mi, the data collection programme of MMC, reports at least 2,500 migrant deaths on land routes from the Horn of Africa towards the North African coast between the end of 2014 and 2016, which is most likely an underestimation.

In the context of ‘Sinai trafficking’ it was estimated that between 5,000 and 10,000 victims died at the hands of human traffickers in Egypt between 2009 and 2013, mostly Eritreans. Although it assumed that this phenomenon is no longer as prevalent as it once was, 4Mi data as well as anecdotal reports from migrants in Libya and Italy, confirm that migrants from the Horn of Africa are still being trafficked, tortured, held for ransom and sometimes disappear and are never heard of again en route to the Mediterranean in Sudan, Egypt and Libya. Although there is no conclusive evidence that the scale of trafficking, deaths and disappearances became much worse in 2016, it could contribute to the drop in arrivals in 2016.

Lower numbers are leaving Eritrea

Eritrea has been described as one of the world’s fastest emptying nations. The widely quoted estimate – first stated by the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Eritrea in 2012 – is that 4,000 to 5,000 Eritreans are leaving their country every month. Since then, this number has been quoted in numerous articles and reports. This includes a 2014 study by the RMMS, which tried to shed more light on this estimate by exploring the ‘ jigsaw’ of numbers from different sources and concluded that, although plausible, the number could be slightly overestimated. One explanation for the lower number of Eritrean arrivals in Italy in 2016, could be that indeed lower numbers have been leaving Eritrea in 2016 compared to the years before. Earlier in 2016, RMMS reported on a deterioration of the living conditions in Eritrea. Reduced purchasing power and reduced access to cash from remittance flows could have limited the ability of many to fund migration.

In 2014, the Danish Immigration Service published a report based on a fact-finding mission in Eritrea, suggesting significant improvements in human rights conditions in the country and suggesting that asylum seekers registering claims on the grounds of illegal exit and evading national conscription should not be necessarily recognized, and therefore could be returned to Eritrea. After publication of this report, the UK Home Office updated its country guidance on Eritrea and as a result, the refusal rates for Eritrean asylum seekers in the UK in the last three months of 2015 increased from 14 to 66 per cent.

The report was highly disputed and criticized, even by some of the authors involved and by Danish Immigration Service employees, as well as by as by Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch. According to the latter the report was “deeply flawed and more like a political effort to stem migration than an honest assessment of Eritrea’s human rights situation”. Nevertheless, there is a possibility that circumstances in Eritrea are improving and that fewer people are, therefore, leaving the country. Conditions, however, are difficult to verify, especially since most reports on Eritrea are based solely on sources outside Eritrea and do not include an on-the-ground assessment within the country.

In a February 2017 publication by the European Commission it was estimated that 700 Eritreans cross into East Sudan every month, a much lower estimate than before. In 2013, for example, it was estimated 3,500 Eritreans were arriving in Sudan every month. Given the dynamic and constantly changing migration flows in the region, rises and falls in the volume of these flows are to be expected and could in this case be one of the reasons for the lower numbers arriving in Italy.

Conclusion

According to the estimates above, between 48,000 and 60,000 Eritreans should have left Eritrea in 2016. Just over 20,000 arrived in Italy, 50% less than in the previous years. This article explored several contributory causes for this decline, all the more remarkable because the total number of arrivals in Italy hit a record in 2016. While the number of Eritreans along other migration routes out of the region (south, east, north) is negligible, not all Eritreans leaving their country end up in Italy, with some staying in refugees camps in Ethiopia and Sudan and other settling in urban centres (sometimes as undocumented migrants) within and beyond the region. Furthermore, during 2016 interceptions and deportation of Eritreans by Sudan and Egypt have been scaled up and significant, though unknown numbers, tragically never reach their destination: they disappear and do not survive the dangerous journey through the desert or across the Mediterranean. Finally, it seems plausible that fewer Eritreans have been leaving their country than in the years before 2016. It remains to be seen whether the flows to Europe will pick up again with better weather conditions during the European spring and what the impact will be of continuing and increased European efforts to stop the flows.

Note: This article originally appeared on the RMMS Horn of Africa website.