Tensions have been rising for some weeks now along the Mexico-United States border, where more than 7,000 Central Americans recently arrived, after travelling more than 4,000 km from their homelands. These people were part of the so-called “caravan”; a group of several thousand migrants and asylum seekers, from Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador travelling together across the region to apply for asylum in the US or for some in Mexico.

While the share of people traveling along the caravan was actually as little as three percent of the annual overall number of people moving along this route, their progression through Central America over recent weeks and months was highly politicised and attracted maximum media attention, particularly as it occurred in the context of the US mid-term elections. There have been many similar (normally smaller and less publicised) caravans in recent years, but this event has been more disruptive in terms of leading to more media attention and responses than the size of the phenomenon would justify. This includes the attempts by the Trump administration to try to further restrict access to protection in the US, and potentially Mexico, which could affect the access to protection for people travelling in mixed migration flows for years to come.

This article aims at placing the events of the last months in the context of the broader patterns of human mobility in the region over the last decade. It will show that sustained migration flows from the Northern Triangle towards Mexico and the U.S. have been the norm for more than a decade, and that also the routes used have remained the same. On the other hand, the profiles of the people moving are changing, with an increasing number of asylum seekers joining mixed migration flows, as well as the reception policies of destination countries, which are becoming increasingly restrictive.

Is migration from the Northern Triangle a new phenomenon?

Despite the recent alarmist media coverage, there has not been an increase of people leaving Central America in 2018, according to Manuel Orozco, director of the Migration, Remittances and Development Program at the Inter-American Dialogue, and author of a recent report on Central American migration. “Statistically, and in absolute terms, you don’t have an increase in migration, but you have sustained migration going on for nearly 10 years: in 2009 about 150,000 Central Americans left their homelands and entered the United States, the estimates for 2018 show a similar total” Orozco told MMC.

The UNHCR estimated in 2017 that about 500,000 Central Americans irregularly cross the southern border of Mexico every year, though it is not clear how many of these people eventually returned to their countries, in the context of circular migration movements, and how many either stayed in Mexico or crossed irregularly to the US. Overall, about 3.4 million Hondurans, Guatemalans and El Salvadorans are currently living abroad, according to the Migration Data Portal. The number of people from the Northern Triangle living in the US grew from about 800.000 in 1990 to nearly three million in 2016, according to a report by the Migration Policy Institute.

In terms of migration routes, the UNICEF map below shows the three main routes that people in the caravan – and others fleeing the Northern Triangle region – used to reach the US border. These routes correspond to the Mexican rail routes and had been already identified by IOM in 2015 as the main migration corridors used by people looking to get across Mexico. According to UNICEF, these informal routes are often dangerous because people on the move – and particularly women and children – are easy prey for traffickers and exposed to abuses and kidnapping by criminal gangs.

Source: https://www.unicef.org/child-alert/central-america-mexico-migration

If the number of people in mixed migration flows have remained more or less constant over the past decade and the routes used by people on the move also remained the same, what’s new in the most recent patterns of human mobility in the region?

How has migration from the Northern Triangle changed?

There have been in recent years two significant shifts in regards to migration out of Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador: an increase in the number of unaccompanied children and families, and flows previously predominantly composed by people seeking better economic opportunity becoming more mixed, as more people flee violence and persecution in their countries of origin.

Families and unaccompanied children accounted for 36 percent of those apprehended by US border authorities along the border with Mexico in the first half of 2018, compared to ten percent in 2012. This increase of children and women on migration routes is in line with what Maria Hernandez, a projects coordinator for Doctors Without Borders (MSF) in Mexico, has witnessed along migration routes in Mexico. “We are seeing more children and more mothers leaving their country and taking the route that was normally taken mostly by men: in the shelters, and along the roads, there are more women and children”, Hernandez told MMC.

This trend is driven by gender-based violence, according to UNHCR’s report “Women on the Run”. Sixty-four per cent of the 160 Central American female asylum seekers interviewed by UNHCR in the US cited risk of rape, assault, extortion, and other threats as their main reason for fleeing their homeland. The UNHCR report details the extreme levels of violence women in the Northern Triangle face, and notes how El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras rank first, third, and seventh, respectively, in rates of female homicides globally.

These three countries have consistently ranked among the most violent worldwide, and have significantly higher homicide rates than neighbouring Costa Rica, Nicaragua, and Panama. Orozco’s research shows how in Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador an increase in homicides led to an overall increase in the number of people leaving the country. “What’s happening in Central America is an illustration of a global phenomenon where migration is driven by state fragility,” Orozco told MMC.

Other sources concur with this analysis. According to a report by the Washington-based rights agency, WOLA, the Northern Triangle countries are plagued by endemic levels of crime and violence that have made many communities extremely dangerous, especially for children and young adults. Furthermore, the region has been experiencing the most severe drought in decades, which has exacerbated economic and food insecurity in already vulnerable populations.

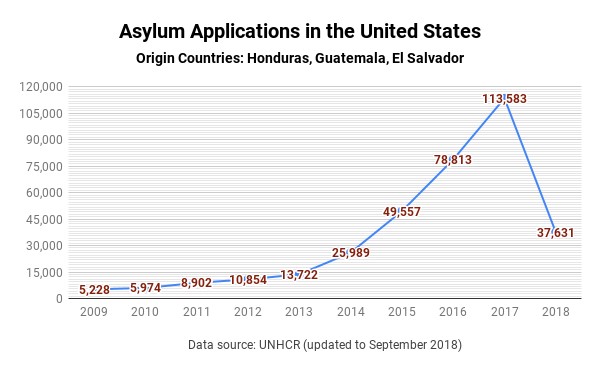

The growing insecurity in the Northern Triangle – for women, children and men alike – has led to a strong increase in the number of asylum seekers in the region. The number of asylum seekers from Northern Triangle countries increased from 10,069 in 2011 to a peak of 81,548 worldwide in 2016, according to UNHCR. In Mexico, asylum applications by Central Americans doubled between 2015 and 2016, and then increased by 119 percent between 2016 and 2017. In the US, more people from Northern Triangle countries applied for asylum in 2013-2015 than in the previous 15 years combined.

Where are migrants and refugees from the Northern Triangle going and how are they received?

As of mid-December 2018 more than 5,000 refugees and migrants amongst those who reached Mexico as part of the caravan were waiting to seek asylum in the US at the border crossing of San Ysidro. The Mexican government has issued temporary residence and work permits to some of the participants, and government officials said there are 100,000 jobs available to Central American asylum seekers. But those who apply for asylum in Mexico may face a long wait because the asylum system is not very ready to process the current workload, according to Donald Kerwin, the Executive Director of the Center for Migration Studies of New York. The average waiting time for asylum applicants in Mexico to get a reply on their application is 3-8 months, even if according to Mexican law asylum applications should be processed within 45 days. The UNHCR regional spokesperson in Latin America, Francesca Fontanini, told MMC that there is a “backlog” in the Mexican asylum system because, “the institution that is dealing with asylum seekers is not prepared to receive such a number in such short time.”

While Mexico has become a de facto destination country, the preferred destination for people fleeing Northern Triangle countries has been and continues to be the United States. However, already back in January 2018 the US Department of Homeland Security characterized the situation as one where “current loopholes in our immigration laws have created an incentive for illegal immigrants who knowingly exploit these same loopholes to take advantage of our generosity”, calling therefore for “responsible pro-American immigration reforms”. In line with this approach, as of November 2018 the US Customs and Border Protection took steps to limit the number of individuals who could lodge asylum claims at ports of entry along the border with Mexico, only accepting a limited number of individuals every day or week for asylum processing, as documented by a recent report by a collective of researchers working at the US-Mexico border.

According to UNHCR, this situation “is forcing many vulnerable asylum-seekers to turn in desperation to smugglers and cross the border irregularly”. The UN refugee agency urged the US administration “to make sure any person in need of refugee protection and humanitarian assistance is able to receive it both promptly and without obstruction in accordance with the 1967 Refugee Protocol to which the United States is a party”.

What’s next for Central Americans waiting at the Mexico-US border?

An unofficial waiting list managed by asylum seekers themselves had over 5,000 names on it as of December 1, and the waiting time to start an asylum application with US authorities was estimated at about two months. Meanwhile, Mexican authorities have begun to relocate the thousands of Central Americans who had been waiting by the border to nearby shelters in Mexicali and Tijuana after rains destroyed the makeshift camp where people were staying. UNICEF expressed deep concern for the well-being of more than 1,000 children who are amongst those waiting for the opportunity to apply for asylum.

As asylum processing of US authorities is stalled, about 1,000 of the US-bound refugees and migrants have accepted voluntary returns back to their home countries, and others have begun to disperse from the border area. The Mexican Commission for Refugee Assistance, in cooperation with UNHCR, has set up temporary offices in Mexicali and Tijuana geared toward providing a response to Central Americans who want to seek protection in Mexico, in an effort to speed up asylum processes, and on December 3, in his first day in office, Mexico’s new President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador announced that he is working with the US and Canada to tackle the issue of Central American migration.

The future of Central American asylum seekers is in the hands of President Obrador and the region’s other political leaders. It has been reported that the Trump administration reached a deal with the incoming Mexican president to implement a “Remain in Mexico” policy, which would force Central Americans who wish to apply for asylum in the US to wait in Mexico while their application is reviewed. At the same time, the US government is considering Mexico’s proposal for a multibillion-dollar international aid package to deter Central American migration. On 11th December, during a meeting with Democratic leaders, President Donald Trump said he was willing to shut down the government if he could not obtain the billions of dollars needed to finance the construction of the border wall between US and Mexico

While it is still not clear what policy the region’s leaders will agree on, it seems likely that the protection options available for people who flee Central America’s Northern Triangle will continue to decline. There is even a risk that, almost paradoxically, due to the global attention the caravan attracted, people who are part of the current caravan, as well as those who went through perilous journeys in hope of finding protection before them, and those who are yet to leave, may see their access to protection restricted for years to come.