The following essay was originally compiled for the Mixed Migration Review 2021 and has been reproduced here for wider access through this website’s readership.

The essay’s author Kerilyn Schewel is a visiting research scholar at the Duke Sanford Center for International Development and a senior researcher at the International Migration Institute.

Hundreds of millions of people across the world choose not or are unable to migrate despite facing migration drivers such as socioeconomic insecurity, dire geoclimatic conditions, conflict, and failed governance structures. This “mixed immobility” has major implications for humanitarian action and policymaking.

Introduction

There are 7.8 billion people on our planet, and of these, only 272 million, or 3.5 percent, are international migrants. In almost every country—rich or poor, peaceful or insecure—most people do not migrate across national borders. Moreover, according to Gallup World Polls, 85 percent of the world’s population would not migrate even if given the resources and opportunity to do so.

Given wide disparities in wages, work, and wellbeing between countries around the world, the general propensity for people to stay put is perplexing. Conventional wisdom and prevailing theories assume people will migrate—or should at least aspire to migrate—to places that offer higher incomes, employment, and other opportunities. Yet, the reality is that migration flows are far more modest than this basic assumption would predict. Why, then, are more people not migrating?

Long neglected by migration researchers, immobility is the subject of a mushrooming body of literature that sheds new light onto this fundamental question. Using a selection of research from around the world, this essay highlights new theoretical and empirical perspectives emerging from this research agenda in order to widen understanding of different ways of not migrating for individuals and communities across the globe. It will show that some of the most vulnerable populations lack the resources to migrate, even as their livelihoods are threatened by climate change, economic insecurity, or political conflict. It will also question why, even in resource-poor or insecure places, many people prefer to stay where they are. It argues that those working with mixed migration need to take two elements more seriously: 1) the significant financial, legal, or even physical barriers many aspiring migrants face in realising a migration project; and 2) the social, cultural, and spiritual dimensions of human motivation and behaviour that can motivate a preference to stay put. The essay concludes by considering the implications of immobility for humanitarian and other actors working with mixed migration, and introduces the “capability to stay” as a one important area for further research.

Theoretical perspectives

Understanding immobility has an important contribution to make to our understanding of migration. Although it is reasonable that migration scholars focus primarily on the causes and consequences of migration, too often this focus treats immobility “as a static, natural or residual category.” This mobility bias leads to lopsided migration theories that overemphasise the drivers of migration and neglect the countervailing forces that resist or restrict these drivers, leading researchers to frequently overestimate actual migration flows. To counteract this mobility bias, a growing number of scholars are beginning to study immobility as a process with its own determinants. Mirroring definitions of migration, immobility may be defined as spatial continuity in a person’s place of residence over a designated period of time. Immobility is always relative to local, regional, or national borders. For example, if we are concerned with understanding who does not migrate internationally, we may examine immobility relative to national borders—i.e., who stays in their home country—recognising many will still be internally mobile. Alternatively, we could also look at who stays put in a particular village or city for their entire lives, or periods of immobility across the life-course.

As greater attention is given to immobility, it would be unproductive to treat it as a fundamentally separate or distinct phenomenon to mobility or migration. Rather, we need conceptual approaches that jointly examine migration and staying as potential outcomes to the same forces of individual, social, and environmental change. This requires rebalancing our understanding of the drivers of migration and displacement with a sophisticated understanding of migration constraints and motivations to stay. This promises to reveal the more multidimensional reality of immobility, and will help us to develop more realistic assumptions, models, and predictions about migration.

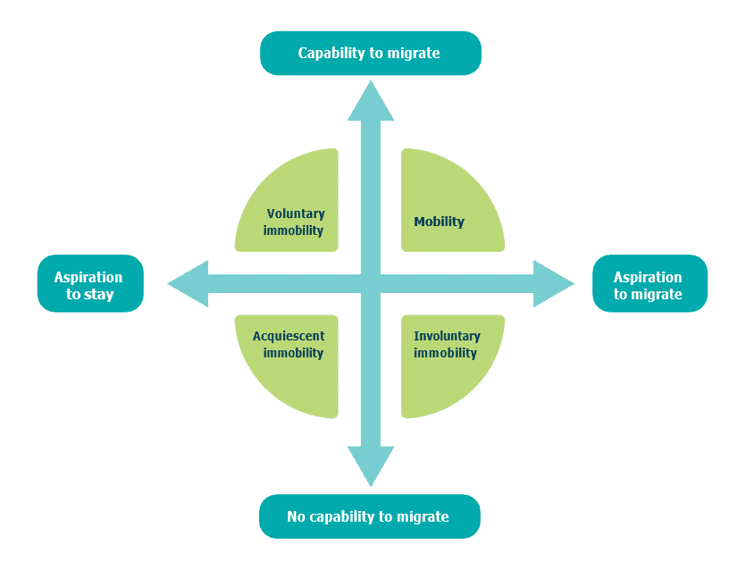

Building on the aspiration/ability model and the aspiration-capability framework—two similar yet distinct approaches for analysing micro-level migration processes—one fruitful conceptual step is to separate the aspiration to migrate (or to stay) from the ability to do so. This distinction allows us to see that both are prerequisites for migration and that the lack of either one leads to different forms of immobility. As Figure 1 below illustrates, this distinction reveals three types of immobility: involuntary, voluntary, and acquiescent. Involuntary immobility refers to those who aspire to migrate but are unable to do so. Voluntary immobility refers to those who have the capability to migrate, but who aspire to stay where they are. The term acquiescent immobility describes those who do not wish to migrate and are unable to migrate.

Source (adapted) and credit: Schewel 2020, 335

The (im)mobility types suggested by this model should be treated as ideal types rather than rigidly distinct empirical categories. They can help researchers see often-overlooked experiences and heterogeneity in immobility. In applying this framework, the tension between these neat categories and our messy reality is also a fruitful friction that can reveal new dimensions to migration and staying processes. In that light, ongoing efforts to apply this framework are generating many important questions. For example, how do aspirations and capability interact over time? Are there important differences in the intrinsic or instrumental nature of migration aspirations? To what degree do aspirations predict future behaviour? How well do these categories hold up in contexts of “forced migration”? Much work remains to flesh out the implications of this conceptual approach for our study of mixed migration and mixed immobility, both in the theoretical and empirical domains.

Nevertheless, this simple framework already reveals much more about different ways of being immobile than indicated by the previous binary division between migration and non-migration. It shows that immobility can result from motivations to stay in place, from constraints on mobility, and/or from the interaction of the two over time. The following section of this essay uses the immobility categories suggested above as an orienting frame to review a wide range of research investigating causes and consequences of immobility in order to shed light on the nature, causes, and consequences of “mixed immobility” around the world.

Examples of mixed immobility

Involuntary immobility

Jorgen Carling first introduced the concept of “involuntary immobility” in a 2002 article that provocatively claimed our times are most likely characterised as much by involuntary immobility as they are by large migration flows. Drawing on rich interview and survey data from Cape Verde, Carling explored the culture of migration that encourages young Cape Verdeans to aspire for a future abroad, and the increasingly restrictive “immigration interface” that deprives many of the ability to leave. His study shed light on the darker side of globalisation, which often facilitates the movement of the privileged at the same time as it introduces new barriers to the mobility of the “unskilled”. He shows how involuntary immobility leads to widespread frustration and unfulfilled dreams. In a new project, Carling and his colleagues are investigating further the consequences of unrealised migration aspirations for individuals, communities, and societies, this time in mainland West Africa, where some of the world’s highest rates of migration aspiration exist.

Stephen Lubkemann applied the term involuntary immobility in a very different context: to describe those who did not move during a fifteen-year civil war in Mozambique (1977-1992). Using ethnographic methods, Lubkemann highlighted the important role labour migration played in the social and economic life of many drought-prone communities before the conflict began. When the civil war erupted, many of these mobility systems were disrupted, and the most disadvantaged were those who were trapped by surrounding conflict, unable to flee their villages. The new constraints on mobility-based livelihood strategies had devastating effects, deepening poverty and insecurity. Lubkemann encourages readers to question whether the disruption and disempowerment we associate with wartime movement are in fact greater for those who are immobilised in conflict settings. He argues that these populations—the “displaced in place”—are theoretically invisible in migration and refugee studies because of the implicit conflation of displacement with spatial movement.

Involuntary immobility in settings of conflict or disasters remains a pressing humanitarian concern. Consider, for example, the Tigrayans who have been immobilised by Ethiopia’s civil war and currently face an impending famine. As Richard Black and Michael Collyer argue, those who have “lost control of the decision to move away from potential danger” present some of the greatest theoretical and practical challenges to research and humanitarian action in crisis settings.

In addition to affecting those who cannot leave their homelands, periods of involuntary immobility can occur during a migration process. Joris Schapendonk interviewed irregular migrants from sub-Saharan Africa heading to Europe and showed how many get stuck in Morocco. Many migrants ran out of money needed to continue their journey, and increasingly restrictive border controls make onward travel into Europe ever costlier and more dangerous. As a result, these migrants became immobilised “in transit”. Similarly, refugees who have fled their home countries may become tied to camps for decades or even generations, unable to return yet never resettled elsewhere. Indonesia, for example, has long served as a transit country for asylum seekers and refugees en route to Australia. But after 2013, when Australian policies to curb irregular migration increased and opportunities for resettlement virtually disappeared, refugees and asylum seekers increasingly find themselves in a situation of “indefinite transit” in Indonesia. As Jennifer Hyndman and Wenona Giles argue, protracted refugee situations are becoming the new normal; “waiting among refugees has become the rule, not the exception”. They argue that refugees who break out of this enforced limbo, daring to seek a life elsewhere, are often vilified as security threats, while the “good refugee” waits in place.

Voluntary immobility

Voluntary immobility refers to those who may have the resources and opportunity to migrate but prefer to stay where they are. When voluntary immobility exists in situations where there are compelling reasons to leave, it often reveals complex “non-economic” priorities that shape how people make decisions to go or to stay. These non-economic concerns are often missed in explanations for migration. Although it is well established that motivations for migration are complex—economic incentives are often interwoven with other social and cultural concerns—many scholars will bracket and set aside the more elusive social and cultural factors and focus primarily on income- maximisation and other material costs and benefits, which are easier to measure. Yet, when the economically rational decision would be to migrate (or at least aspire to migrate), and someone still expresses a preference to stay, researchers are forced to take seriously the social, cultural, and even spiritual values that shape migration decision-making.

Two case studies are worth highlighting in this respect. In the Pacific Islands, Carol Farbotko and Cecilia McMichael show that, even facing rising sea-levels and coastal degradation, many Indigenous populations prefer to remain on their ancestral homelands for cultural and spiritual reasons, including a deep connection to land and place-based identity, knowledge, and culture. They highlight that Pacific indigeneity and spirituality are “important cultural resources for those at risk, helping to navigate an often tenuous balance between hope and despair.” Some islanders even express a preference to die on their traditional territories over relocating, “representing a new type of agency and resistance to dispossession.” Climate justice, Farbotko and McMichael argue, requires taking seriously these desires to stay in place. Rather than defaulting to planned relocation in climate-affected sites and territories, the reality of voluntary immobility should be taken seriously and all opportunities to adapt in place should be considered thoroughly and carefully. A first step is for policies to explicitly recognise voluntary immobility as a valid measure and outcome in contexts of environmental degradation.

Across the globe, in a very different setting, Jenny Preece examined residential immobility in “declining” urban neighbourhoods in England. In many post-industrial settings, demographers and labour economists ponder why people are not moving to areas that could offer better employment opportunities. Preece shows that, in contexts of low-paid and insecure work, “place-based mechanisms of support” become particularly important, be they the social, emotional, and financial support of family and friends, or word-of-mouth connections to informal job opportunities. In this context, staying in place was often an active choice that enabled households to “construct networks of information and support that counterbalanced an insecure employment context.” By investigating the motivations behind immobility at the “bottom of the labour market,” Preece reveals a rationality in migration decision-making that prioritises social networks and local community in the face of economic precarity. Motivations to stay in place, then, were neither strictly economic nor social; drawing on local social networks enabled people to actively adapt to their precarious economic circumstances.

Acquiescent immobility

The concept of acquiescent immobility applies to those who have neither the aspiration nor the ability to migrate. One might question whether their immobility is “voluntary” in the same way as someone with the ability to migrate who nevertheless decides to stay. The term ‘acquiescent’ implies an acceptance of constraints, and the Latin origins of the word mean “to remain at rest.” This category can be difficult to identify empirically, as it is challenging to say who has the ability to migrate if someone has never tried and does not want to. Yet the concept has important theoretical value, if only to highlight that many people in very challenging circumstances still prefer (or resign themselves) to stay where they are.

One survey of migration aspirations in Senegal, for example, found that almost one-third of young respondents who said they could not meet their basic needs had no desire to migrate. This is particularly striking considering the research question was framed not in terms of whether they would migrate, but rather posing an ideal scenario: “Ideally, if you had the opportunity, would you like to go abroad to live or work during the next five years, or would you prefer to stay in Senegal?” Qualitative interviews from the same study suggest many potential explanations for acquiescent immobility. Maybe people never meaningfully consider migration; their aspirational horizons are limited to what they know. Perhaps people feel committed to their home-place, and as Albert Hirschman once put it, choose “voice” (i.e., to express discontent and hope for change) rather than “exit” (i.e., migration). Maybe, as one Senegalese respondent suggested, they value living in a spiritually rich community that is materially disadvantaged more than a materially rich culture that is spiritually deprived. Perhaps they simply want to stay with their parents or children.

In an ethnographic study of desired immobility in rural Mexico, Diana Mata-Codesal suggests another reason for acquiescent immobility. She uses the term “acquiescent” to highlight that some people do not have clear desires around migration one way or the other. She describes the “inertia” that can lead people to remain “lukewarm about the role of (im)mobility in their range of available projects for life-making”—regardless of their ability to migrate. One implication is that we should not assume everyone goes through an active process of “migration decision-making,” the outcome of which is reflected in their mobility or immobility. Perhaps a more interesting question is when and why some individuals consciously engage in migration decision-making, while others never really consider it.

Mixing it up: transitions between categories

Lest the immobility categories reviewed above appear static, it is important to emphasise that aspirations and capabilities shift over time and thus individuals can move between migration and immobility categories. Research exploring these transitions are adding new dynamism to the aspiration/ability model and aspiration-capability approaches. One such study by Yasmin Ortiga and Romeo Luis Macabasag examines the experience of involuntary immobility for Filipino nurses who are unable to move internationally and, in response, become internally mobile. They find that after graduating, many nurses move frequently within the Philippines to secure clinical work experience in order to remain employable to foreign hospitals. Yet, with time, the costs and burdens of constant internal movement compel many nurses to “either develop adaptive preferences that subdued their original aspirations or acquiesce to their inability to leave the country.” This study highlights that involuntary immobility is a difficult state to live in; difficult too are the demands of making life choices always in light of the desire to leave. Adjusting aspirations—and thereby moving into acquiescent immobility—is an important coping mechanism in the face of significant obstacles to migration.

Migration-immobility interactions

It is common to speak about “contexts of forced migration” or areas characterised by a “culture of migration.” The implication of the words “context’ and “culture” is that everyone leaves, or at least aspires to leave. But even in these settings, where the forces driving migration are strongest, many can remain involuntarily or voluntarily immobile. In this light, another study by Diana Mata-Codesal examines “different ways of staying put” in a village in the Andean Ecuador. This village is shaped by a culture of migration; irregular migration to the United States is considered a rite of passage for young men. Those who were thwarted from realising this dream became involuntarily—and socially—immobile in the village. However, Mata-Codesal also describes those who, in the same setting, consciously decide to stay put. One voluntarily immobile woman, for example, finished her education and secured a job and steady income locally; aware of the hardships of life in the United States as an irregular immigrant, she did not desire to live abroad. Mata-Codesal highlights that this kind of voluntary immobility is more likely to exist for those who have opportunities for upward social mobility locally. In this place, it is more possible for women who are not expected to migrate, and thus have time to complete their education, but who rely on the remittances of their migrant family members to finish their schooling.

Zooming out from the individual and assuming a household, family, or even village-based perspective reveals complex interactions between migration and immobility. The migration and remittances of some family members can enable the immobility of others, while those who stay put enable migrants to go by caring for land, local investments, children, or aged parents. This symbiotic relationship between migration and immobility has economic, social, and cultural dimensions. As Paolo Gaibazzi reveals in his ethnographic study of “rural permanence” in Gambia, villagers who stay are “committed to reproducing the agrarian institutions, sociality and values that make life and outmigration meaningful and acceptable.” In other words, migration often assumes meaning through the “mooring” of an origin.

Future directions: the capability to stay

Just as migration in the future will ideally be more voluntary than involuntary, immobility will ideally reflect an active choice to stay rather than a denial of the right or resources to migrate. To advance research towards this goal, more theoretical and empirical attention needs to be given to the capability to stay. The capability to stay is inspired by the “capability approach”, a development theory that places the freedom to achieve wellbeing as the goal of development and suggests evaluating development in terms of people’s capabilities to do and be what they have reason to value. From this perspective, exploring capability to stay entails asking whether people have realistic options to achieve their life aspirations where they are.

The aspiration-capability framework presented here remains overshadowed by a mobility bias in the sense that migration and staying aspirations tend to be examined only in relation to the capability to migrate.

Yet, it is not clear how best to incorporate the capability to stay into this model because, unlike the aspirations to stay or to migrate, the capability to stay is not simply the opposite of the capability to migrate. The capability to migrate refers to the financial, human, and social resources required to change one’s residence from origin A to destination B; it is revealed or confirmed when people migrate. The capability to stay is conceptually trickier: it refers to having real opportunities and resources to realise one’s life aspirations in origin A. It is not necessarily revealed through immobility; those who stay in place yet are unable to realise their aspirations locally remain deprived of the capability to stay.

Calls to enable people to stay in place are often criticised for giving implicit support to initiatives to decrease migration, to migration controls. and to immigration regimes that deprive people of the right to movement. This critique is frequently voiced against development aid targeting the imagined root causes of migration. It was also voiced when former UN High Commissioner for Refugees Sadako Ogata declared in 1993 that crisis- affected populations should have the “right to remain”, because it may have indirectly supported policies that restricted the right to seek asylum. When a focus on staying concentrates solely on outcomes, and when it implicitly portrays migration as something negative—a “problem that needs to be ‘fixed’ by appropriate policies”—this usually results in superficial measures that restrict rather than enhance wellbeing.

The concept of the capability to stay is different, because enhancing the capability to stay does not require diminished migration. It builds on how Hein de Haas defines human mobility: as people’s capability to choose where to live, including the option to stay, rather than as the act of moving or migrating itself. From a normative perspective, then, all people should have the capability to stay, recognising that many of those who have it will still choose to migrate.

Conclusion

It is important to bring immobility into the mixed migration paradigm, and in doing so, recognise that immobility is itself “mixed”. Just as there is a wide spectrum of forced to voluntary migration, so too is there a spectrum of forced to voluntary immobility. The different kinds of immobility described above—involuntary, voluntary, and acquiescent—give some indication of this heterogeneity.

Recognising these different kinds of immobility can enhance policy effectiveness in many settings. For example, as research into effects of the global Covid-19 pandemic grows, it reveals that for many low-wage workers, the pandemic has exacerbated the economic need to migrate, yet public health restrictions have simultaneously constrained the ability to do so. Finding ways to alleviate involuntary immobility will be critical to restoring the livelihoods of affected populations. Similarly, in situations of humanitarian crisis, it is important to recognise that those who are trapped by conflicts or disasters are some of the most vulnerable. Identifying how humanitarian actors can best reach immobilised populations and how humanitarian practices can evolve to reduce the likelihood of involuntary immobility in crisis situations remains an urgent issue.

For policymakers working in areas threatened by climate change, it is helpful to exercise caution around sweeping accounts of either massive migration or massive trapped populations. Rather, the task is to better understand how environmental stresses interact with other well-established migration drivers and constraints to give rise to different migration and immobility outcomes. Further, policymakers should not assume all those whose livelihoods are threatened by climate change desire to leave; incorporating voluntary immobility as a reasonable aspiration of local populations demands significant investment in local adaptation strategies to climate insecurities, not only relocation programming.

Finally, in the field of development theory and practice, more attention should be given to the capability to stay, particularly exploring what is required to enhance the capability to stay without restricting or undermining the right to movement. Reducing migration remains the main objective of many development policies that seek to address the “root causes” of migration. Yet, often failing to achieve their objective, development resources are reallocated towards migration “management” and control. This is the worst of all possible outcomes: using development aid to restrict mobility without meaningfully improving lives and livelihoods in origin places—essentially trapping people in a state of involuntary immobility.

Development practitioners should return to the question of whether “development” truly enhances the wellbeing of local populations, and the capability to stay provides one conceptual lens through which to ask whether development is doing this. Beyond policy, there are also important implications for migration and development research. For example, a growing body of research shows that human and economic development tends to increase aspirations and capabilities to migrate from low-income countries. But do these occur against the backdrop of decreased capabilities to stay, particularly in rural places? Understanding how aspirations and capabilities to migrate interact with aspirations and capabilities to stay can shed new light on the drivers of mixed migration and mixed immobility.