More than one year after the outbreak of conflict in Yemen in March 2015, warfare rages on. Widespread conflict, characterized by persistent air strikes, armed clashes and shelling has wreaked havoc across the country, resulting in large-scale destruction of infrastructure and depletion of services, as well as claiming thousands of lives and causing massive displacement. By early April 2016, there were more than 2.7 million internally displaced persons (10% of the Yemeni population), and more than 175,000 had sought refuge in neighbouring countries in the region, some 85,000 of whom had fled to countries in the Horn of Africa (Djibouti, Ethiopia, Somalia and Sudan).

Yemen’s geographical position on the south-western tip of the Arabian Peninsula has long positioned the country as a gateway for the movement of people and goods from the Horn of Africa. Migrants, asylum seekers and refugees (primarily of Ethiopian and Somali origin) have traditionally travelled from the coastal towns of Obock in Djibouti and Bossaso in Puntland, Somalia across the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden/Arabian Sea to Yemen. Monitoring patrol teams established by UNHCR and partners (Danish Refugee Council, Yemen Red Crescent Society, and the Society of Human Solidarity) have patrolled the coastal roads of the Red Sea, Gulf of Aden and Arabian Sea since 2006, providing information on the numbers of people arriving on Yemeni shores.

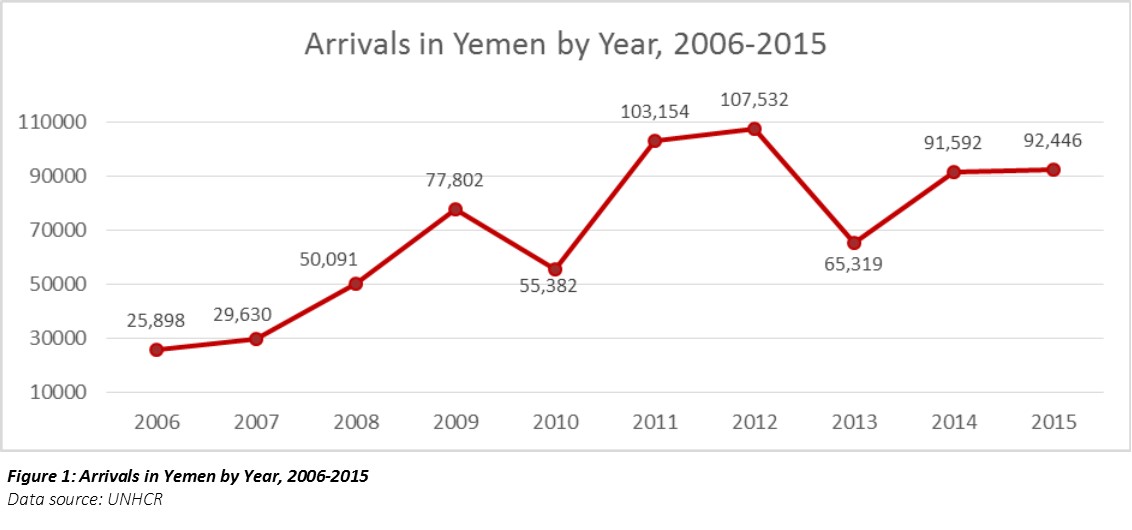

With the exception of 2010 (as the result of a war along the Yemen-Saudi border and a Yemeni security force clamp down on the arrival of Somali nationals) and 2013 (following the mass expulsion of migrant workers from Saudi Arabia), the numbers reveal a year-on-year increase of the arrival of migrants and refugees in Yemen. In 2011 numbers shot up, surpassing the 100,000 person mark for the first time. A combination of growing unrest among Ethiopian Oromos (who form the majority of Ethiopian ethnic groups arriving in Yemen) in 2010 that they were unlikely to benefit from substantial development and humanitarian aid received by the Ethiopian government from international donors, and a devastating famine in Somalia in 2011 spurred large numbers to move towards Yemen in search of better conditions and opportunities. This was compounded by an unstable situation in Yemen following the start of the Arab Spring in early 2011, and the resulting weakening rule of law, that encouraged many to take advantage of the government’s competing priorities to move into and through Yemen with relative ease.

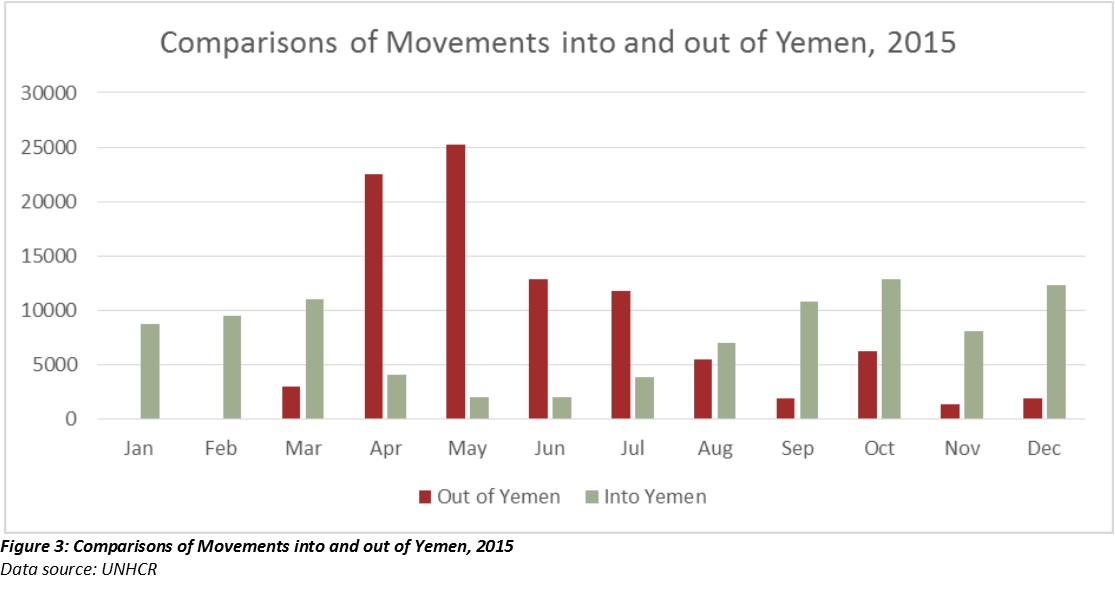

The 2015 Yemen conflict, which triggered a new bi-directional flow along the strait with the arrival of persons from Yemen back into the Horn, appears to have done little to deter groups of migrants and refugees from continuing to cross into Yemen. In fact, Yemen arrival figures in 2015 were the highest recorded since 2012, and the third highest since monitoring began. Due to the disruption of monitoring missions caused by the conflict in 2015, it is possible that the arrivals figures in 2015 were even much higher.

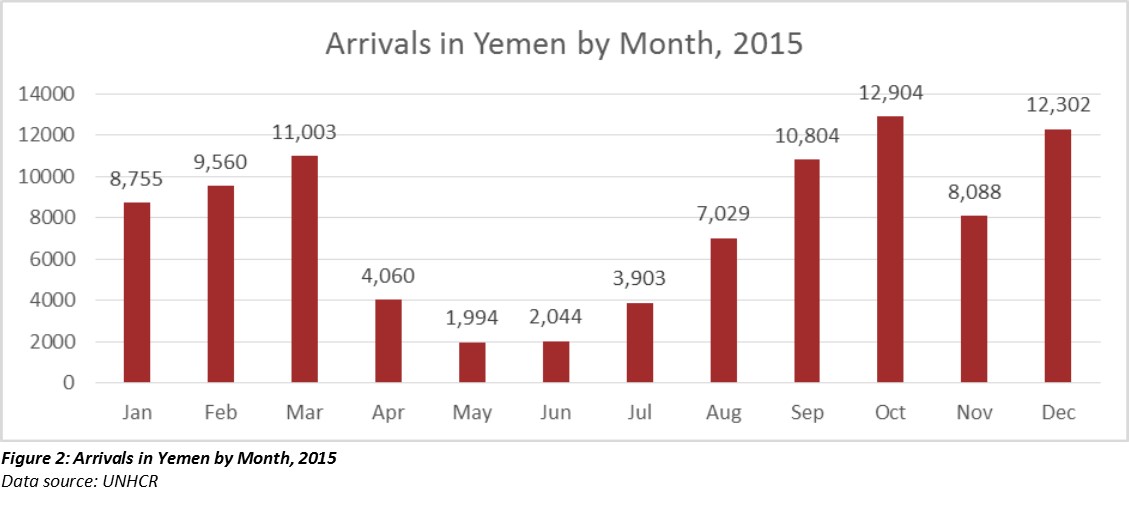

A more detailed look at the figures in 2015 shows a steady climb in arrival figures in the first three months of the year, followed by a sharp drop in April and May, coinciding with the outbreak of conflict at the end of March. In June however, as outward flows from Yemen began to decline, arrival figures began to climb again, with a peak in October, the highest monthly arrival figure ever recorded since 2006. These statistics not only show an increasing demand for travel to Yemen despite the risks associated with a conflict zone, it also shows that migrants and refugees may perceive the unrest to facilitate a better environment for undetected passage. It also alludes to the ability of smuggling networks to quickly regroup and reorganise their business model in such situations.

Changing Tides

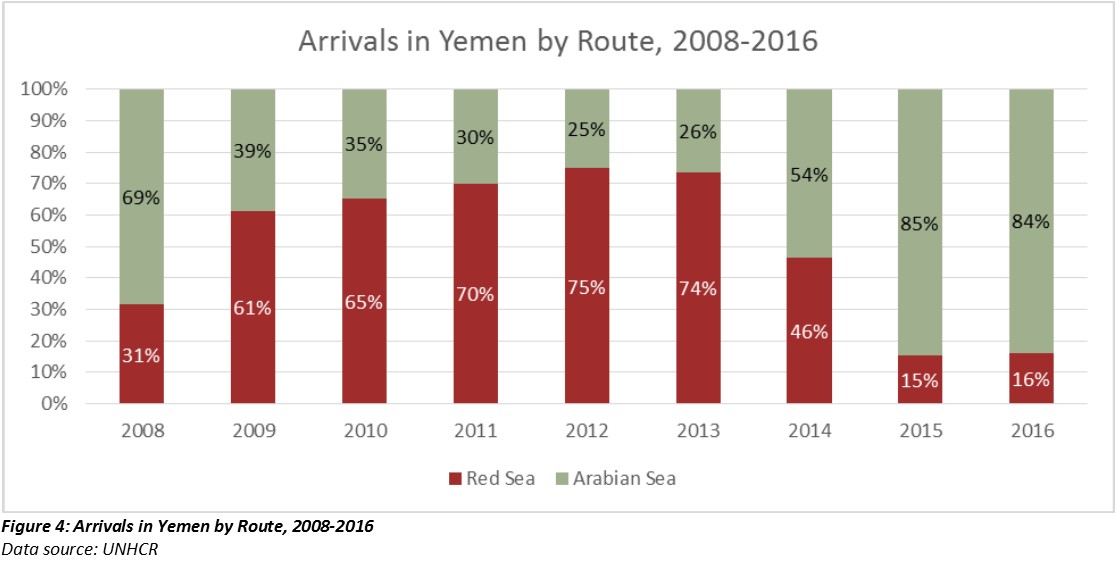

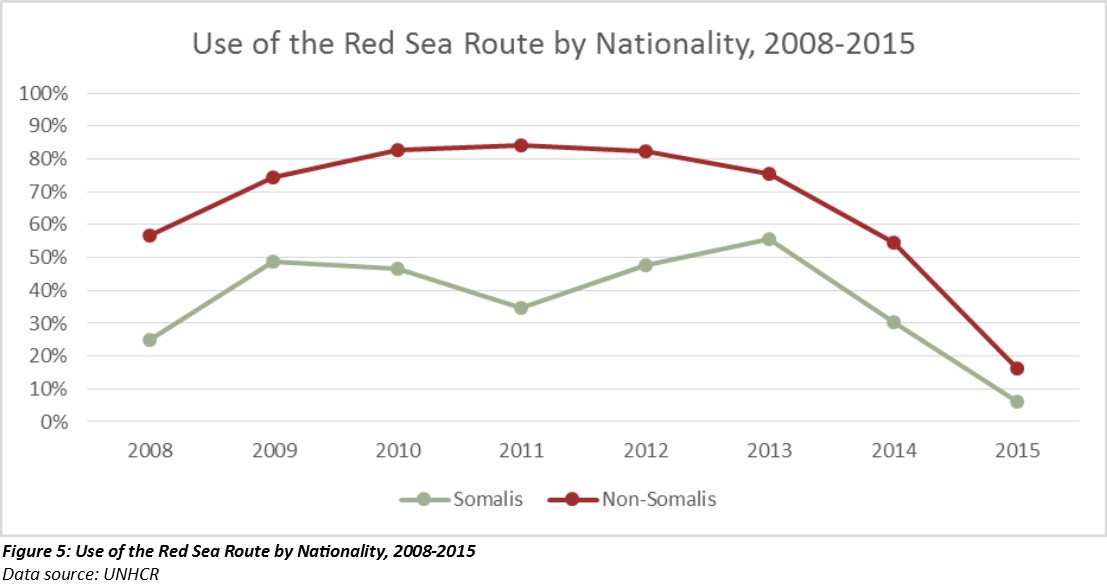

Historically, movements to Yemen have occurred along two main routes: one out of Obock, Djibouti (Red Sea), and another from Bossaso in Puntland, Somalia (Arabian Sea). UNHCR monitoring missions along the Yemen strait have been measuring the movements along the two distinct routes since 2008. With the exception of 2008, the Red Sea had consistent popularity, averaging at 69 percent of recorded movements between 2009 and 2013.

In the course of 2014 however, figures began to show a gradual shift indicating an increased preference by migrants and refuges to travel to Yemen using the Arabian Sea. By the end of 2014 this had resulted in an inversion in the routes’ popularity, with the Arabian Sea arrivals accounting for 54 percent of movements. In 2015, this changing trend had firmly entrenched itself with 85 percent of migrants and refugees opting to use this route. Statistics in first quarter of 2016 also confirm this new trend, at 84 percent, which pending any major changes in the context in the region, is expected to continue throughout the year. Nonetheless, new arrivals continue to land along the Red Sea coast even though some of the most intense fighting has been in Ta’iz governorate. The statistics provided may not be fully representative of how many more may have landed as the area is inaccessible to UNHCR and its partners.

Abuse and torture along the Red Sea coast

Migrants and refugees travelling to Yemen from the Horn of Africa face various protection risks that arewidely documented. These risks are faced at all steps of the journey – at origin, while in transit on land, during the sea journey, and on arrival in Yemen. RMMS’ reports Desperate Choices, Blinded by Hope, andAbused and Abducted have observed the risks faced by people on the move including, physical and sexual violence, abduction and kidnapping, extortion, and torture. In Blinded by Hope 70 percent of interviewed Ethiopian migrants that had returned from Yemen had either witnessed or experienced ‘extreme physical abuse, including burning, gunshot wounds and suspension of food for days’.

Data received from the monitoring missions show that these abuses are more pronounced along the Red Sea route from Obock, Djibouti, and in particular kidnap for ransom. No cases of abduction have ever been reported along the Arabian Sea route. According to UNHCR, patrols along the Arabian Sea are manned by UNHCR’s partner Society of Human Solidarity, who the capacity to receive all new arrivals on the shore regardless of the time preventing smugglers and criminal networks an opportunity to carry out abductions.

The smuggler networks between the point of embarkation in Obock and disembarkation in Yemen were extremely coordinated in sharing information on when boats would set off and arrive. Once migrants/refugees landed in Yemen, they would be abducted and taken to smuggling dens for weeks on end, until they paid extortion fees to secure their release. If they were unable to pay they would be physically beaten, raped, tortured or put to work before eventually being released. Oftentimes migrants travelling further north after their release would be recaptured by other smugglers and go through a similar process.

The threat of abduction and kidnapping for ransom remains a significant threat for those moving, and particularly Ethiopian nationals who are perceived to be able to pay ransoms more readily than their Somali counterparts.

RMMS monthly summaries continue to include reports on the abduction of migrants/refugees arriving via the Red Sea coasts. In March 2016, migrants reported 218 cases of abduction and 29 cases of trafficking, amounting to 77 percent and 10 percent respectively of all protection incidents reported in that month. It is believed that the shift in migrant and refugee departure points from Djibouti to Bossaso in 2014 (and to date) can be directly attributed, at least in part, to the extent of the abuses witnessed and experienced on the Red Sea route. Anecdotal and unconfirmed evidence received from migrants and refugees suggests that smugglers and boat crews moving from Bossaso to Yemen treat them better than those in Djibouti. Interviews with humanitarian actors in Bossaso also suggest that migrants and refugees face little harassment from local communities, police and authorities, which may encourage them to use the Arabian Sea route.

Based on the available information it appears that the risk of abduction and abuse on the Red Sea route is the major cause for the shifting nature of mixed migration movements from the Horn of Africa to Yemen. Consistent reports by migrants and refugees arriving in Yemen appear to have channelled back to those contemplating moving in places of origin, pushing more to depart from Bossaso. The shift may also in part be attributed to the increased chances of detention of new arrivals for irregular entry into the country along the Red Sea where the military patrol coastal areas, and to the intensified fighting in Ta’iz governorate, where a lot of the arrivals land. Moreover, monitoring reports show that new arrivals have been hit by air strikes and more recently forcibly disembarked before reaching the coast to avoid detection by the Yemeni military or Saudi-led coalition forces, resulting in more migrants and refugees opting to use the Arabian Sea.

Nonetheless, migrants and refugees continue to land along the Red Sea coast. More than 4,600 people have plied this route between January and March 2016. For Ethiopian migrants (who now account for 85 percent of people moving to Yemen) the Red Sea route is quicker, and cheaper, which may explain why so many still choose to use that passage. But even that route from Djibouti may become more difficult and more expensive. Anecdotal evidence suggests that the Djiboutian government has instituted a crackdown on Ethiopian migrants, prompting them to move into Somalia and depart from Bossaso.

Despite the recent shifts in the mixed migration flows to Yemen we can continue to expect that migrants and refugees, and especially Ethiopian nationals, will continue to cross from the Horn of Africa to Yemen.

An upcoming RMMS briefing paper on Yemen will provide a more in-depth analysis on the bi-directional flows of refugees, migrants and returnees between the Horn of Africa and Yemen.

Note: This article originally appeared on the RMMS Horn of Africa website.