The Greek Coast Guard rescued 340 migrants off the coast of Crete after a boat carrying the migrants bound for Italy capsized in the Mediterranean Sea on June 3, 2016. Four migrants were less lucky: they drowned in the Mediterranean. The boat reportedly originated in Egypt and capsized in waters in Egypt’s exclusive economic area.

The Crete incident cast a spotlight on Egypt as a country of transit and its policies towards the mixed migration flows from the Middle East and the Horn of Africa.

Located where Asia, Africa, the Mediterranean Sea and Red Sea meet, Egypt has long been a transportation hub for both capital and labor. Recently, Egypt’s proximity to the Horn of Africa, relative stability and safety when compared with Libya, and access to sea-lanes bound for Europe have made Egypt an attractive transit country for migrants and asylum seekers leaving the Horn of Africa and seeking opportunity in Europe.

Migrants and asylum seekers pursuing the western route to Europe from the Horn of Africa have few choices in their journey’s route: all are forced into choosing to enter one of Libya or Egypt after traversing Sudan. Libya affords a relatively short passage across the Mediterranean, which may contribute to why 70,000 migrants chose Libya as their final port of call before going to Italy in the first six months of 2016.

Egypt as Safe Haven compared to Libya?

For at least 7,000 migrants and asylum seekers crossing to Europe from Egypt in the first six months of 2016, Libya’s dangers may outweigh Libya’s virtues. Migrants may want to avoid kidnapping and paying up to USD 8,000 for ransom or persecution at the hands of the Islamic State. Testimonies from migrants and asylum seekers in Italy suggest that the Libyan government institutions may exacerbate protection challenges migrants and asylum seekers may face. A June 2016 Amnesty International press release said the Libyan Coast Guard sent migrants and asylum seekers crossing the Mediterranean Sea back to Libyan detention centres, where they faced abuse and torture. On-the-ground observers in Egypt, interviewed by the Regional Mixed Migration Secretariat (RMMS) were unanimous in the sentiment that more migrants and asylum seekers were flowing into Egypt relative to 2015. “There have been more migrants in the past three months [arriving in Egypt] than in the entire year before,” said one observer, “People from [Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Somalia] are all coming.”

Another observer said, “Every week, I personally run into three or four new arrivals. Sometimes, they come every day.”

The rise in migrants and asylum seekers traversing Egypt reported by the interviewed observers corresponds with other sources. The International Organization for Migration (IOM) recently reported a “spike” in migrants in Egypt requesting direct assistance in 2016, with more requests for direct aid in the first six months of 2016 than in all of 2015 combined. Frontex, the European border control agency, stated the flows from Egypt doubled since last year.

Observers on the ground attribute the shifting dynamic in Egypt to the ongoing instability in Libya and a lack of alternatives. “[Migrants] are scared of terrorists killing migrants [in Libya],” said one observer, “The recent developments in Libya make people think that Egypt is safer.”

Another observer agreed, “After the instability in Libya, Egypt is the most direct path to Italy.”

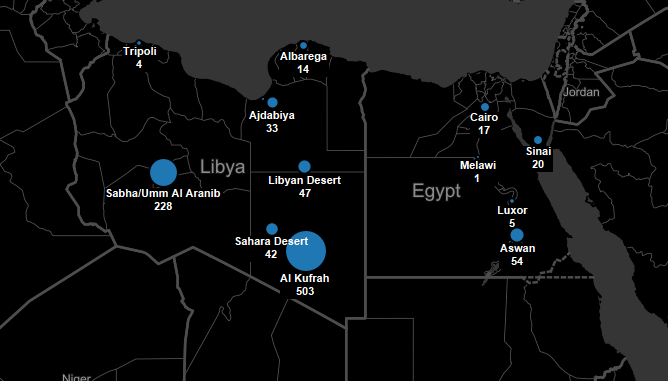

Data from RMMS’ 4Mi programme also correspond with the observers’ assertions of Egypt as a relatively safer alternative to Libya. 159 4Mi respondents reported a total of 876 migrant deaths in Libya between June 2015 and June 2016, in contrast to the 503 respondents who reported 100 deaths in Egypt between September 2014 and June 2016. Further, the deaths were reported in all regions of Libya, with most reports stemming from Kufra District in Southern Libya, a region migrants and asylum seekers must pass through if their journey takes them directly from Sudan into Libya. On the other hand, deaths in Egypt are largely concentrated around Cairo and Aswan.

Figure 1: Deaths in Libya and Egypt

Further, adding to the smaller risk of death on the move, the trip to Egypt may be cheaper than the trip to Libya. 4Mi respondents reported that the median amount spent totaled USD 3,000 on their journey from the Horn of Africa to Egypt, relatively cheaper compared to the USD 4,500 spent on average on a migrant’s journey from the Horn of Africa to Libya.

The Psychological and Physical Risks of Egypt

While Egypt may offer less risk of death and an economical alternative to the Libyan option, traversing Egypt still takes a psychological and physical toll on migrants and asylum seekers who choose that route.

For example, 4Mi respondents reported 146 incidents of gender-based violence in Egypt between September 2014 and June 2016, of which 95 incidents included rape. For comparison, 71 incidents of gender-based violence were reported in Libya between June 2015 and June 2016, of which 37 incidents included rape. Some of the difference may be explained by the difference in the number of interviews conducted: 503 interviews were conducted in Egypt, and 159 interviews were conducted in Libya. 219 people reported witnessing or experiencing incidents of physical abuse primarily committed by smugglers and police in Egypt, 249 people reported being detained by their smuggler, and 104 people reported witnessing or experiencing extortion in Egypt between September 2014 and June 2016.

“Egyptians don’t like new arrivals because they cannot interact with the new arrivals,” said one observer, “And new arrivals don’t understand what Egyptians are doing.”

Other observers interviewed by RMMS said newly arrived migrants and asylum seekers from the Horn of Africa wear very different clothing from longtime Egyptian residents, which singles new arrivals out for mistreatment and discrimination. “Most Egyptians are fine, but the [xenophobic] minority is becoming more vocal as the number of migrants increase,” said one observer, “The local community do not like the number of [migrants] coming and going.”

While all nationalities face mistreatment and discrimination, one observer stated Ethiopians face particular mistreatment, due to lingering resentment over the Nile River water usage dispute.

Most migrants and asylum seekers from the Horn of Africa try to leave Egypt as soon as possible, according to all the observers interviewed, but some people are forced to stay in Cairo or other Egyptian urban centers to make enough money to cover the USD 2500-3000 cost of the final sea voyage to Europe. Female recent arrivals can find positions as cleaners or babysitters; however, male recent arrivals rarely find work as Arabic is critical for positions typically filled by males.

Stranded in Egypt

According to on-the-ground observers, Egypt is no longer seen as a destination country for migrants and asylum seekers from the Horn of Africa. While risks to migrants’ and asylum seekers’ safety and reduced job opportunities for recent arrivals may figure into the calculation, asylum seekers are particularly discouraged from seeking refugee status and protection by the long waiting times for appointments with UNHCR for asylum seeker registration. “People used to try to register at UNHCR, but now the wait time is 3-5 months,” said one Ethiopian observer, “[UNHCR] just rejected 200 people from our community [for asylum], so now crossing the sea is [the viable option.]”

Observers described UNHCR asylum seeker registration cards as vital to accessing services. “UNHCR cardholders have a lot of access to [government] services, [which non-cardholders do not have],” said one observer.

UNHCR registration cards also shield cardholders from government detainment. Detainment in Egypt has become an increasing concern for migrants, according to on-the-ground observers. Media reports indicated UNHCR was aware of a number of Eritreans detained in Cairo’s Qanatir prison.

Similarly, observers said there are now fewer boat departures, though on larger watercraft, to Europe, which leaves migrants vulnerable to detainment by Egyptian authorities after becoming stranded on Egypt’s coast. “The police are becoming more alert,” said one observer, “There used to be a lot of boats [leaving for Europe], at least one per week last year, but this year, the police are much stricter.” Between March and June 2016, Egypt arrested 5,076 people for illegally leaving the country. When the arrest figure is combined with the reports from the observers, the average boat’s carrying capacity leaving Egypt is implied to be approximately 300 people.

“There are many people detained along the Mediterranean,” said another observer.

Migrants and asylum seekers are mostly detained on charges of unauthorized exit from Egypt, not unauthorized entry. The government passed a bill that would criminalize human smuggling in conjunction with human trafficking but would not criminalize irregular migration in November 2015. However, while irregular migration was decriminalized, Egypt’s criminal code still bans leaving the country without official documents and authorization, resulting in the detention of a large number of migrants awaiting deportation to their home countries.

The EU’s Role in Egypt

European leaders have been vocal supporters of Egypt’s migration policy and encouraged further steps to staunch the flow of migrants and asylum seekers transiting through a potentially unstable Egypt. European leaders, such as Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbanand German Interior Minister Thomas de Maziere, recently visited Cairo to discuss European cooperation and assistance in combatting terrorism and irregular migration with Egyptian president Abdel Fattah el-Sisi. Olivier Onidi, the deputy director of the European Commission’s department of migration and home affairs, urged EU lawmakers to engage Egypt on the issue more deeply on June 18, 2016.

According to documents leaked to the Spiegel Online, the European Union is currently engaging in a concerted strategy that keeps migrants and asylum seekers off their shores. “The EU [is] rewriting its foreign policy so that it serves the single objective of stopping people from coming to Europe,” an Oxfam press release stated.

The European Union plans a comprehensive package of assistance, cooperation and engagement with the el-Sisi administration and other African governments. The EU-sponsored New Migration Partnership Framework adds to the EU Trust Fund, now totaling 3.1 billion EUR, and is aimed at stimulating development in African countries while curbing illegal migration. An additional component of the Framework will be an investment package designed to trigger additional investments of up to 31 billion EUR in participating countries. The aid is seen to be contingent on the successful curbing of outflows to Europe as part of the EU’s strategy to provide both carrots and sticks to transit countries.

As well, the EU will expedite returns of African migrants who illegally entered the EU to Africa, despite the lack of readmission agreements with all African countries except Cape Verde.

Readmission agreements allow for the readmission by states into their territory of both their own nationals and nationals of other countries – ‘aliens’ – in transit who have been found in an illegal situation in the territory of another state. A larger readmission agreement between the EU and African countries, as promised by Article 13 of the Cotonou Agreement of 2000, was rejected by African governments at the Valletta Summit on Migration in November 2015 after concerns over deported migrants’ potential long term detention in proposed processing centers in third countries within Africa and the fate of irregular migrants’ social safety net contributions in Europe went unaddressed.

Whither the Migrants?

Should the EU successfully assist Egypt in curbing outflows originating in Egypt and across the Mediterranean Sea entirely, mixed migration flows from the Horn of Africa will be forced back into the flows in the short term through Libya, which has significant protection challenges, three major governments competing for legitimacy, and general instability. Libya’s continued insecurity and three-sided civil war has made any EU-negotiated agreement with Libya difficult or impossible to implement fully. Moreover, Libya is not a participant in the African Union-European Union Khartoum Processes, launched in 2014, aimed at tackling the challenges posed by the mixed migratory flows of irregular migrants, refugees and asylum seekers between countries of origin, transit and destination between Horn of Africa and Europe and developing cooperation at the bilateral and regional level to tackle irregular migration and criminal networks. Libya’s fragility, however, has not prevented the EU from engaging the UN-backed Government of National Accord (GNA) based in Tripoli by promising to train the coast guard and funding operations implemented by the Tripoli-backed Department of Combatting Illegal Migration. By choosing to support the GNA over the Libyan House of Representatives (HoR) based in Tobruk, the EU runs the risk of antagonizing the Tobruk-based HoR. Without the EU’s support, the HoR could ignore migration flows to Europe until the EU provides support similar to the support provided to the GNA, which would be hindered by the EU’s recognition of the GNA as the sole legitimate government. In that case, the EU’s policies towards Libya designed to end mixed migration flows across the Mediterranean may be at best ineffective.

Over the long term, the economic incentives the EU is proposing to African countries for curbing migration may have the opposite effect of what the EU intends. The development packages aimed at stimulating development in countries of origin and designed to keep potential migrants in their countries of origin may indirectly financially enable people to migrate to the European Union through the additional income the packages generate.

Finally, Egypt’s policies, supported in large part by EU incentives, have done nothing to protect irregular migrants from human rights abuses. Further, the EU’s strategy to curb irregular migration flows to Europe through the aforementioned incentives may only redirect and embolden the migrant flows to make the journey from the Horn of Africa to Europe.

Note: This article originally appeared on the RMMS Horn of Africa website.