The following essay was originally compiled for the Mixed Migration Review 2020 and has been reproduced here for wider access through this website’s readership.

The essay’s author Chris Horwood is the Director of Ravenstone Consult and independent consultant.

International migration is irreversible and predominantly an urban affair. International regular labour migrants as well as asylum seekers, refugees, and irregular migrants flock to cities all over the world. An even greater number of internal migrants do the same. Migration is thought to contribute to around half of urban population growth in Asia and Africa, and up to 80 percent in China and Thailand. “Human mobility is the signature of the urban era we live in, which makes understanding the impact of migration so important.”

Cities as concentrations of talent, investment, culture and close-living consumers can transform dreams and hopes into reality by offering work, security, refuge, health facilities, education and training services, and community. As places where newcomers settle or just pass through, cities offer both opportunities and risks to refugees and migrants; equally refugees and migrants can be both beneficial and burdensome for cities.

Cities are therefore on the frontline of a longstanding transition towards multi- culturalism and diversity that some argue is essential for the success of the 21st century metropolis.

City growth entwined with mobility

The history and life of cities has always been entwined with mobility. Whether internal or international, forcibly displaced or traveling voluntarily, people on the move have always been urbanisation’s driving force. And urbanisation has been the dominant trend of human society in modern times.

The staggering 100 -year rise from 750 million city dwellers in 1950 to an expected 6.7 billion in 2050, means that overwhelmingly cities have been and will continue to be the main locus of human organisation and activity. With migrants contributing to a significant proportion of urban growth, it is increasingly municipal authorities who take the lead in managing migration in their urban planning and implementation. This introductory essay provides an overview of the situation and highlights the most salient opportunities and challenges faced by both those in mixed migration flows—who are increasingly drawn to, and find themselves living in, these “arrival cities”—and the authorities that manage them.[1]

The unfinished trajectory

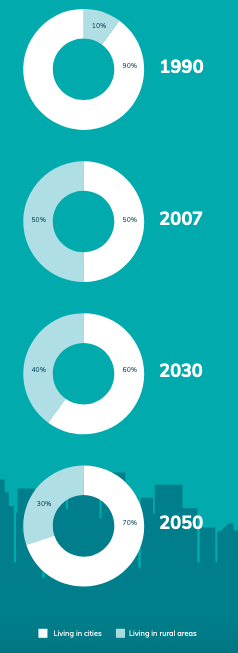

Globally, urbanisation is on an unfinished trajectory, one that describes the huge human transition from countryside to city that has been spurred by shifts away from employment in agriculture everywhere. The rapid diversification of the global economy set in motion by the First Industrial Revolution that began in the middle of the 18th century, with the introduction of factories, mass production, and rising wages, continues today through what has been termed the Fourth Industrial Revolution: the growth of mobile supercomputing, machine learning, intelligent robots and other “new technologies that are fusing the physical, digital and biological worlds, impacting all disciplines, economies and industries.” With less than a tenth of the global population living in urban centres in 1800, the transition gathered pace in the 20th century with this proportion rising to 30 percent in 1950, to 55 percent in 2018, and is projected to become 68 percent by 2050.

The watershed year of 2007 was the first time more people lived in urban centres than in rural areas. But behind these global proportions and averages, individual nations and regions have their own stories, moving at different speeds and are expected to peak—if they have not already—at different times. Brazil, for example, charged forward from being 10 percent urban in 1900 to 80 percent urban in 2000. Some 90 percent of urbanisation in the next 30 years is expected to take place in Asia and Africa, while in other regions that urbanised earlier, some cities are experiencing population decline. In some cases, such as London and New York, population levels are only being maintained or re-stocked by international migration.

The UN calculates that today the most urbanised regions include North America (with 82% of its population living in cities in 2018), Latin America and the Caribbean (81%), Europe (74%) and Oceania (68%). The level of urbanisation in Asia is now approximating 50 percent, while Africa remains mostly rural, with 43 percent of its population living in urban areas.

According to UN projections, by 2030, the world will have 43 megacities with more than 10 million inhabitants, most of them in developing regions. But some of the fastest-growing urban agglomerations are cities with fewer than 1 million inhabitants, many of them located in Asia and Africa. “While one in eight people live in 33 megacities worldwide, close to half of the world’s urban dwellers reside in much smaller settlements with fewer than 500,000 inhabitants.” Urbanisation and migration are two interrelated processes. Urbanisation, defined as the increasing proportion of a population living in urban areas, usually involves some form of migration, whether internal or international.

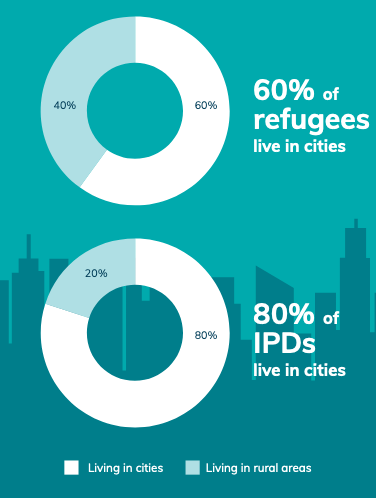

Refugees and internally displaced populations (IDPs) living in cities

Urban and rural population of the world, 1990-2050

Source: Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Global Migration: Resilient Cities at the Forefront. (2017)

City “fever”

Not all cities are established organically over hundreds of years; some are created quickly and grow rapidly following deliberate plans, the emergence of new workforce-hungry industries, special opportunities, or particular historic events. Some speculate we are in the midst of a new city “fever”. In Egypt, in addition to 22 existing or nearly completed new cities, plans to build another 19 were announced in 2019. Hundreds of new cities that sprang up in China in recent decades were mostly built, and subsequently populated by, migrants. “Some of these manufactured cities have been extraordinary successes. Shenzhen rose from a rice paddy into one of the world’s most dynamic metropolises—its economy is the size of South Korea’s—in just three or four decades.” India, anticipating and encouraging huge migration from villages to cities, embarked on the “world’s most ambitious planned urbanization programme” in 2015, with the Smart Cities Mission to build the next generation of Indian cities. Successful urban concentration of economic, cultural, and human capital attracts more migrants, from both the countryside and abroad.

City formation and growth has always depended on the influx of people. These are mostly internal migrants coming suddenly into big cities from rural areas, or, in a process called “step migration,” moving through urban hierarchies from smaller towns to larger ones and then to cities. Many others arrive from abroad, practicing circular migration or more commonly chain migration.

Concentrations count

International migrants and refugees comprise only a small proportion of the 4.2 billion people now living in cities across the world. The number of international migrants globally reached an estimated 272 million in 2019, an increase of 51 million since 2010. Currently, international migrants comprise 3.5 percent of the global population. Data from 2019 indicates that global displacement has reached an estimated 79.5 million people, of which 26 million are registered refugees and the rest internally displaced people.

Most international migrants and those arriving irregularly live and work in cities, as do refugees and asylum seekers. Contrary to widespread perception, the dominance of the refugee camp is reducing as millions of refugees choose cities. According to the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR), “over half of the world’s refugees now live in the slums of some of the world’s biggest cities such as Bangkok in Thailand, Amman in Jordan, and Nairobi in Kenya.” In recent movements from Venezuela, the vast majority of refugees have ended up in towns and cities of Brazil, Chile, Columbia, Peru, and Ecuador. The city is the new de facto refugee camp. With nearly all migrants— internal and international—heading for cities, and a (growing) majority of the world’s population living in urban areas, migration to cities can’t be ignored, but can it be counted?

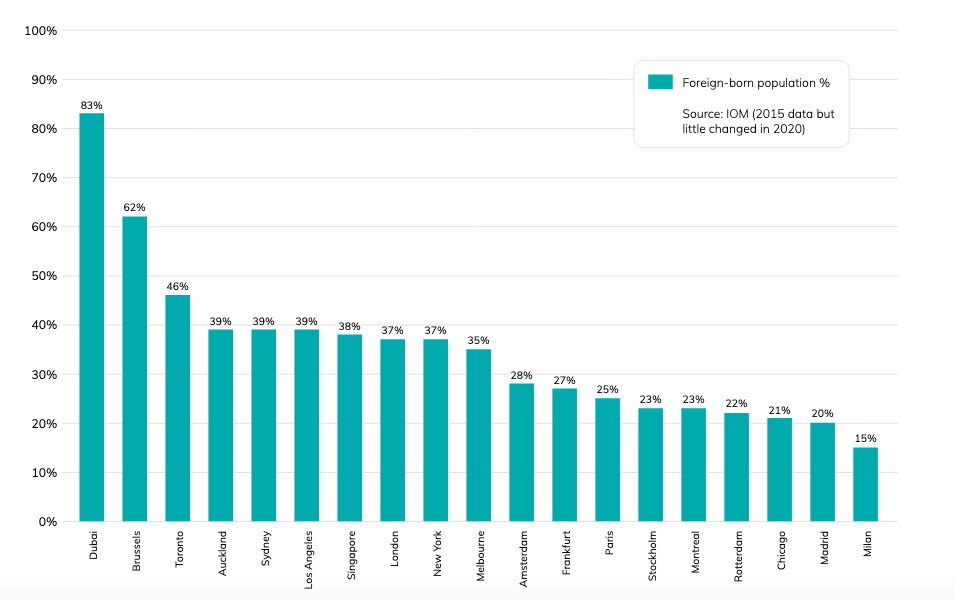

The proportion of foreign-born residents in major cities has been growing rapidly in recent decades. It is not uncommon for many so-called “world” or “global” cities to have at least a quarter or well over a third of their residents from overseas.[2] Migrants tend to be concentrated more in global cities than other parts of a country, contributing sometimes to distorted perspectives of the proportion of migrants in a country and influencing political views.[3] On average across the world, it is estimated that around 20 percent of all foreign-born residents are concentrated in a relatively small number of “global” cities, which in some countries attract the lion’s share of the national total. For example, in 2015, of Canada’s 6.8 million foreign-born population, 46 percent lived in Toronto; 38 eight percent of the United Kingdom’s foreign-born population lived in London; and 28 percent of Australia’s 6.6 million people born overseas were concentrated in Sydney and Melbourne.

Figure 1 below illustrates the proportions of foreign -born residents in 19 of the world’s major cities, nine of them in Europe. The difficulty of tracking new arrivals and people on the move (as described below), coupled with the large numbers of irregular and “hidden” migrants and asylum seekers, means that these figures may well be underestimates.

Foreign-born population in major cities as share of total city population

Embedded but invisible

Nearly half of all international migrants are known to reside in 10 highly urbanised, high-income countries. Establishing detailed data of urban populations can be challenging, let alone data concerning regular and irregular migrants. One of the problems is the speed of growth and the velocity of change. “Even basic data about urban populations are lacking in many of the fastest growing cities of the world. Existing methods for gathering vital information, including censuses and sample surveys, have critical limitations in urban areas experiencing rapid change.” This is particularly true of “hidden populations” in cities missed by traditional approaches.

Existing data collection methods struggle to generate representative data on mobile populations arriving in cities and on mobility within cities. Population censuses tend to be infrequent and, being conducted at households, generally only enumerate people who are formally registered as permanent residents, thereby excluding temporary or undocumented migrants, and often overlooking those living in informal settlements, unmapped locations, or places where enumerators don’t feel safe. Where urban growth is very rapid, by the time census results are published, their data might be out of date. Moreover, “undocumented migrants may try to conceal their identity for fear of detection by the authorities, or they may be unreachable during the day as they tend to work long hours and are not at home when enumerators call.” The result is that despite being increasingly embedded in cities across the world, those in mixed migratory movements—including asylum seekers and refugees—are often invisible, which has serious implications for city planning and service provision, let alone protection of the most vulnerable.

Heterogeneity dominates

What migrants and refugees find when they arrive in cities and urban centres is highly varied, reflecting the myriad urban situations that receive those on the move. Cities’ responses and level of attention they pay to these newcomers is highly heterogeneous. A random selection drawn from the virtually endless list of migration experiences might include any of the following:

- A Rohingya refugee who left Bangladeshi camps to try his chances with some kinsmen in India, living precariously under the radar of an unwelcoming host government.

- A Nepali labour migrant working in Dubai in intense heat and living in a dormitory, enjoying few if any rights or legal protections, but benefiting from a previously unobtainable salary.

- A Venezuelan family arriving in Bogotá, Colombia, housed by the city with many others and given minimum support from international and national organisations. Their children attend school while parents look for work.

- A Chinese internal migrant who, along with millions of others, is given permission to leave a remote rural area to work in a factory in a new city where rental prices and food costs are high, working hours long, and legal status and access to services uncertain.

- A Nigerian car mechanic, rescued on the Mediterranean and now selling watches in Italian cities, already sending money home and sharing a room in a disused building with many others.

- A Senegalese asylum seeker in Valletta, Malta working as a day-labourer with a family construction company while he waits for the results of his asylum claim.

- Two Somali brothers running a small kiosk in a South African township, fearful of anti-foreigner attacks while trying to organise a smuggler to bring their young wives and children from Dadaab refugee camp in Kenya to join them.

- A Syrian family living in Germany, the wife a physiotherapist who easily found employment, the ex-policeman husband retrained as a metalworker. After intensive language classes both speak German and help out at the local primary school in their free time.

- A Mexican couple who reached the United States but who have no papers. They live in a low-quality one-bedroom flat. He works in the orchards of California, she as a maid in a coastal town and is pregnant. She can use the local hospital and later the schools will admit their child.

The immediate needs and concerns of new arrivals centre around what kind of shelter, employment and working conditions they find, whether they have protected or supported status in the municipality they find themselves in, and the extent to which their families enjoy access to health services, education, psychosocial support and protection and so forth. These needs are common to all those travelling in a precarious or irregular manner across borders, and to those staying weeks, months, or years in a transit or destination city.

Labour migrants moving with a pre-agreed contract and through government or private employment programmes, as well as refugees benefiting from assisted resettlement or return packages, may reckon on more organised and structured assistance, but the many others will have to discover and negotiate for themselves what help exists in their new location. One study surveying major European cities in 2016 found that consistently, “the major challenges reported by cities and local governments regarding refugees’ and migrants’ arrivals are housing, education and employment.” Various essays in this Annual Review, including “First Responders…”(page 200) will delve deeper into these challenges.

Security cannot be guaranteed

The reception new arrivals face in cities ranges from hostile and dangerous to welcoming and supportive. Migrants may find they have been driven to migrate, in part, by environmental issues such as the impact of climate change, only to find the cities they arrive at also face or will face similar threats. Equally, people may flee violence, persecution and insecurity to encounter dangerous environments in cities where levels of crime— including violent crime such as homicide—are high and where they may become victims of sexual violence and/ or assault and robbery. In some cases, they may become embroiled in crime themselves, joining gangs or resorting to theft to survive or cope. Additionally, migrants and refugees can fall prey to sexual and labour trafficking and exploitation, risks that can be as real in cities of the global North as they are in those of the South. These risks are explored in two essays, “Risky cities, mean streets” (on page 178) and “Climate exposure – the complex interplay between cities, climate change and mixed migration”.

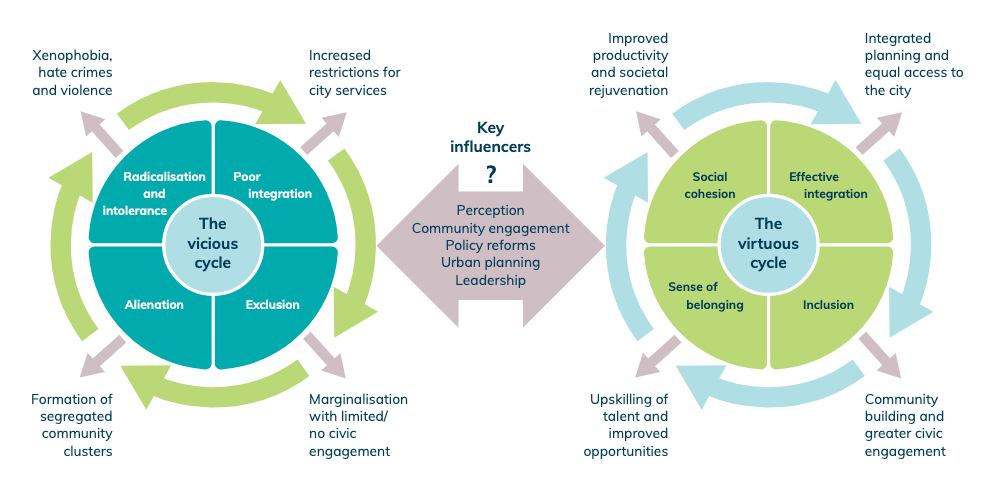

Vicious and virtuous cycles

The essays in this Annual Review explore the spectrum of experiences, initiatives, and plans that cities provide migrants and refugees. Contradictions may exist between national and municipal treatment of newcomers; at the city level the prevailing attitude of the existing community may also be at odds with the authorities’ policies and provisions. The growth of “sanctuary cities” is of special interest in this regard and is explored in more detail in in the essay entitled “Sanctuary cities: solidarity through defiance” that looks at the contested space between national and municipal responses to mixed migration. In the face of increasing numbers of refugees and migrants in cities, how they are treated is critical to whether the experience results in a virtuous or vicious cycle, and not just from the perspective of refugees and migrants there, but also that of the city itself.

Source: World Economic Forum. (2017) Migration and Its Impact on Cities

Poor integration, alienation, structural or cultural exclusion, and intolerance are typical characteristics of the vicious cycle that results in marginalisation, segmented communities and social discord and/or crime and possibly radicalisation. By contrast, cities that work with migrants and refugee groups to enhance social cohesion, inclusion, effective integration and offer newcomers a sense of belonging stand a high chance of activating a virtuous cycle that harnesses and facilitates conditions for diverse benefits to cities. “The arrival of migrants in urban settings can have a transformative effect in terms of their demographic, cultural, political and economic characteristics. The policies of municipal authorities are critical to ensuring migrants’ integration within and contribution to the overall development of localities.” While migration policy is often discussed nationally, the lived reality of settlement and integration is uniquely local and urban.

The success of many of these cities is to a large extent tied to their success in actualising the hopes and dreams of the thousands of migrants and refugees who choose to settle there. When they succeed, the result can be a strong economy and a vibrant ‘cosmopolia’; when they fail, the result can be poverty, segregation and social tension.

Research on urbanisation has found that expanding populations have been the primary driver of rapid GDP growth in major cities, and migrants account for a significant portion of this trend.

Alternative models

Not all governments or cities subscribe to the above approach and instead of recognising virtuous or vicious dynamics work according to alternative models. For example, the proportion of non -nationals in the employed population in countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council and Lebanon and Jordan, (35 million in 2019, 31 percent of whom were female) is among the highest in the world, ranges from 56 to 93 percent, with a regional average of 70 percent. Foreign nationals make up the majority of the population in Bahrain and Kuwait and account for more than 8 of every 10 people in Qatar and the United Arab Emirates. But these workers do not expect and are not permitted to settle permanently; they have limited rights and freedoms, no path to citizenship and are not invited to have family members join them. The cities built and maintained by these migrant populations have no interest in inclusion, integration or equality. Discrimination is high between native population and migrant workers and their treatment is often the subject of human right reports. Migrants in the 6 GCC states account for over 10 percent of all migrants globally.

In China huge numbers of internal migrants are given temporary jobs to build cities and infrastructure while supplying labour to new industries. These “floating populations” are not offered integration or inclusion. On the contrary, they are treated differently from the resident population and afforded different rights and reduced access to services. The rapid development of China’s economy meant the demand for labour in the coastal cities in particular has been relentless: by 2015, official statistics reported that the floating population had grown to a staggering 247 million, accounting for around 18 percent of the total Chinese population.

Transit cities and smuggling hubs

Some cities bustle with a cocktail of mobility, being places of origin, destination and transit in the mixed migration dynamic. Nairobi is an example, where residents may be planning to leave to live in cities abroad, while tens of thousands of others arrived as international or internal migrants, often without documentation, to settle or at least try their luck and find refuge. One of the most economically vibrant urban area in the whole of East Africa is Eastleigh, a suburb of Nairobi dominated by hundreds of thousands of Somali refugees and migrants that have made it a transnational hub. At the same time, Nairobi is a transit city for many who aspire to move on to Southern Africa, Europe via North Africa, or the Middle East and Gulf states, and as such it boasts an industry of facilitators, smugglers, and purveyors of false documentation and international transport. In different ways, cities like Bangkok, Cairo, and Tripoli have similarly complex and multifarious profiles.

In some cases, such as Agadez in Niger, transit migrants and the smuggling business that serves those about to cross the Sahara desert towards the North African coastal cities (and for some beyond) are critical to a city’s economy. These smuggling centres are key hubs with concentrated expertise that lubricates migratory movement while benefiting economically. Their importance and prevalence are explored in the essay “Smugglers’ paradise: cities as hubs of the illicit migration business”, on page 152 of this review.

New global governance and cooperation

Unlike the cases of the Gulf and China above, many cities and municipalities, particularly those in more open and democratic societies, seek to find solutions to ensure migrants and refugees settle well. As discussed, migration is primarily an urban phenomenon that falls increasingly under the responsibility of city rather than national authorities, encouraging cities to adopt new and hybrid approaches to urban governance. “The twin forces of urbanisation and global migration have created a rich field of action and experimentation in cities around the world on integration strategies for migrants,” but recent global and international efforts are also increasingly focused on enabling cities to achieve better management. Management based around inclusion and integration, which itself is not only based on principles of rights and equality (anti-discrimination and anti-racism) but also practical necessity. Irrespective of national level politicking or regulations it is cities and towns that are left with the responsibility to address the quotidian needs and issues of migrants and refugees.

The essays in this Annual Review detail some of the international efforts to support urban governance around migration. They explore inter-city cooperation, mentorship programmes, and how urban management relates to the global compacts on migration and refugees adopted in 2018 and to the Sustainable Development Goals. The New Urban Agenda, a roadmap adopted by world leaders in 2016, is seen as the delivery vehicle for the SDGs in urban settlements, where 17 of the goals apply to migrants and refugees.

The International Municipal Movement has a history going back more than 100 years, to the 1913 creation in Belgium of the Union Internationale des Villes. Prominent members of the movement include United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG), the largest organisation of local and regional governments in the world. Headquartered in Bonn, Local Governments for Sustainability is a global network of almost 1,800 towns, cities of local and regional governments that have made a commitment to sustainable development. UN-Habitat works in over 90 countries to “promote transformative change in cities and human settlements” and is increasingly engaged with the issue of migrants and cities, implementing actions such as the Mediterranean City-to-City Migration Project, led by the International Centre for Migration Policy and Development, and hosting—alongside UCLG and the UN’s International Organization for Migration (IOM)—the 2017 Global Conference on Migration and Cities.

There are many other international collaborations and initiatives that promote various urban agendas, such as the Cities Alliance (hosted by the UN’s Office of Project Services, the Global Mayor’s Forum, Metropolis, Cities of Migration, the Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate & Energy, Eurocities, C40 Climate Leadership Group, Smart Cities Association, and Cities-4-People, to name but a few. Some have a strong online presence as hubs for exchange, such as the Joint Migration and Development Initiative (M4D Net) which brings together almost 5,000 migration practitioners and policymakers from around the world. Some organisations focus on the inclusion and integration of migrants and refugees, like UNESCO’s European Coalition of Cities Against Racism, which emphasize the need for “welcoming cities” and for fighting xenophobia towards the new arrivals.

A stronger role for mayors

Established in 2018, the Mayors Migration Council (MMC) is one of many initiatives aimed at fostering international collaboration between urban administrators.[4] It emerged from the discussions leading up to the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration, and the realisation that cities handle more of the practical aspects of integrating migrants and refugees than do national governments. The MMC, UCLG, and IOM co-steer the Mayors Mechanism, which works to include local and regional authorities within the Global Forum for Migration and Development (GFMD) process, “bringing their voices and expertise into state-led deliberations, and intensifying the dialogue between different levels of government and different stakeholder groups.” The crowded sector of urban organisations may be in need of a voluntary governance structure and coordination itself, particularly around specific issues such as responses to refugees and migrants. One of the Mayors Migration Council’s ambitions is to provide leadership and coordination in this sub-sector. However, in recent years—and particularly since the migrant or refugee “crisis” of 2015/2016 in Europe—agencies and fora dealing with urban themes have become more alive than ever to the issues around migration and asylum.

Transitioning to integrated and inclusive cities

Many cities are aware of the need for and have implemented policies to enhance integration and inclusion. While much progress has been made, overall there are major challenges and many other large urban centres and cities are only starting to gear up. Various studies concur that if cities are to achieve integration and inclusivity they need to move away from biased and negative perceptions of migrants and refugees towards more active civic engagement with migrants while embracing their community participation. They need to change from ineffective—or in some cases non-existent—migration and integration polices and reduce the policy misalignment between federal, state and city governments. The sudden surge of refugees and migrants into Europe in 2015 and 2016, for example, served as a wake-up call for many municipalities and prompted more comprehensive approaches. Reactive, role- based, and process-driven leadership should give way to a conception of urban planning that incorporates future contingencies in view of the inevitable growth of the proportion of migrants and refugees in many towns and cities in the coming years.

The rising number of migrants and refugees in cities presents municipalities with both challenges and opportunities in eight critical areas: housing, education, employment, transport, utilities, sanitation and waste, integration and social inclusion, and safety and security. All these issues are discussed with the help of examples in the essays and interviews of this Annual Review; the success of cities’ responses to them demands a holistic, cross-departmental approach by local and national governments.

Echoing this observation, a recent report on European cities by IOM and the Migration Policy Institute identified some key recommendations in a context where European cities have seen a shift towards “mainstreaming” diversity and inclusion. Mainstreaming here means meeting the needs of diverse groups across all services instead of through stand-alone integration programming, and from seeing inclusion and diversity not as a solely sociocultural issue but as one relevant to all aspects of city life. “Many of these cities have stepped up to the task and are now working to translate emergency responses into long-term plans to make the most of diversity.” The report also underlines the importance of strong city leadership and the critical role mayors play with regard to immigrants by giving them a greater say in local policies and community life, especially in cities with recent or rapidly diversifying migrant populations. It concludes that “the real test of governance structures is in the design and delivery of local services, including where they are located and how they are linked to one another.” As they plan for a more inclusive future, cities are increasingly using Singapore’s “45-minute city with 20 -minute towns”, or Sydney’s “30-minute city” to deliver key amenities and services as a guiding principle.53

This Annual Review promotes the notion that while migration policy may be polemical and discussed at the national level, the lived reality of settlement and integration is explicitly local and urban. Migration-focused agencies and research bodies, as well as refugee- centred organisations, are re-doubling their focus on these concerns.

But 2020 is a year of extraordinary uncertainty, where the Covid-19 pandemic and the responses to it have created unprecedented conditions whose impact may be felt for many years to come. Some commentators are describing the fallout in revolutionary terms, predicting global transformations in a wide range of social, cultural and economic areas, including migration. Alan Gamlen goes so far as to ask whether the pandemic will herald “the end of the age of migration”. Various interviews and the “Hot zones” essay on page 210 of this Annual Review explore how migrants in cities might be particularly vulnerable to the virus and how pandemics affect migration and migration policy as well as urbanisation trends.

Nevertheless, whether those on the move are doing so internally or across borders, regularly or irregularly, or in a voluntary or forced manner, as long as they continue to concentrate in cities and towns, the outcomes and fate they face in these arrival cities will primarily be the product of choices made by those that run municipalities.

[1] The term is taken from: Saunders, D. (2011) Arrival City: How the Largest Migration in History is Reshaping Our World. London: William Heineman.

[2] A global city, also called a power city, world city, alpha city or world centre, is a city that is a primary node in the global economic network. The concept comes from geography and urban studies, and the idea that globalization is created and furthered in strategic geographic locales according to a hierarchy in the operation of the global system of finance and trade. Not surprisingly these cities attract migrants and refugees.

[3] Although intolerance of multiculturalism, diversity and migrants is more associated with communities with low or no migrant presence rather than cosmopolitan cities.

[4] Others include (aside from national organisations for mayors and international organisations for cities); the Global Parliament of Mayors, Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy, World Mayors Council on Climate Change, Mayors for Peace etc.