In 2015, 3,770 people perished while crossing the Mediterranean, while in the first six months of 2016, 2,861 people were reported to have passed away on the Mediterranean. In the second volume of the Fatal Journeys report released in June 2016, the International Organization for Migration (IOM), estimates that, globally, a record number of 5,400 migrants have died trying to cross borders in 2015 and an additional3,100 lost their lives in the first five months of 2016.

The available data from IOM indicate that the large majority of these migrant deaths occurred on sea crossings, with the Mediterranean being the most deadly route globally. According to UNHCR, in 2016 the odds of dying while on the Central Mediterranean route from North Africa to Italy are as high as one in 23. Additionally, IOM reports a total number 103 people to have died on the move in the Northern Africa / Sahara region in 2015, and 95 in the Horn of Africa (all on the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden crossing to Yemen).

Based on these reports, more people die on the doorstep of developed countries than when en route in developing countries and one might conclude that the Mediterranean crossing is the most dangerous part of the passage from the Horn of Africa to Europe. However, migrants and refugees from the Horn of Africa arriving in Libya, Egypt or Europe consistently indicate that even more people might die while crossing the Sahara Desert than while crossing the Mediterranean, but reliable data on migrant deaths on land routes have so far been unavailable.

RMMS’ 4Mi programme indeed suggests that the gap between the number of deaths on the Mediterranean and the number of deaths on land routes in North Africa is not solely explained through a disparity in actual risk but also through a disparity in reporting.

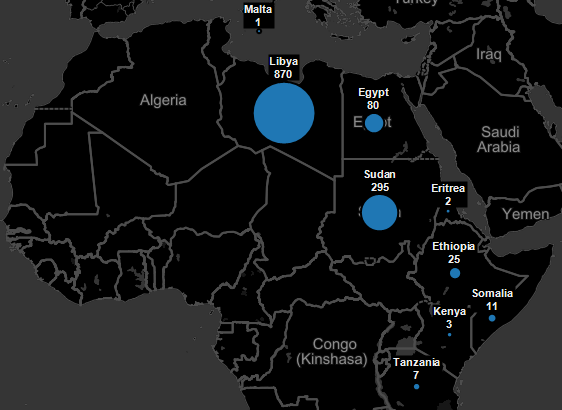

Figure 1: Number of Migrant Deaths by Country

After interviewing over 1,300 migrants between 2014 and 2016, 4Mi reports that 1,245 people perished on the move in Libya, Sudan and Egypt combined. Libya, in particular, was reported to be the site of the majority of 4Mi reported deaths at 870 deaths reported. While there is the possibility of double counting (with interviewed migrants reporting the same incident twice) and inaccurate reporting (there is no system in place to verify reported deaths), the relatively small number of migrants interviewed by 4Mi monitors suggests the 1,245 figure is a conservative estimate of those who actually perished. When compared to the official figure of 103 migrants and refugees dead while on the move in Northern Africa from IOM, 4Mi data suggests a much higher real death toll. Based on 4Mi data, it would be safe to assume the number of migrants and refugees dying before reaching the shores of Egypt and Libya is even higher than the number of deaths at sea.

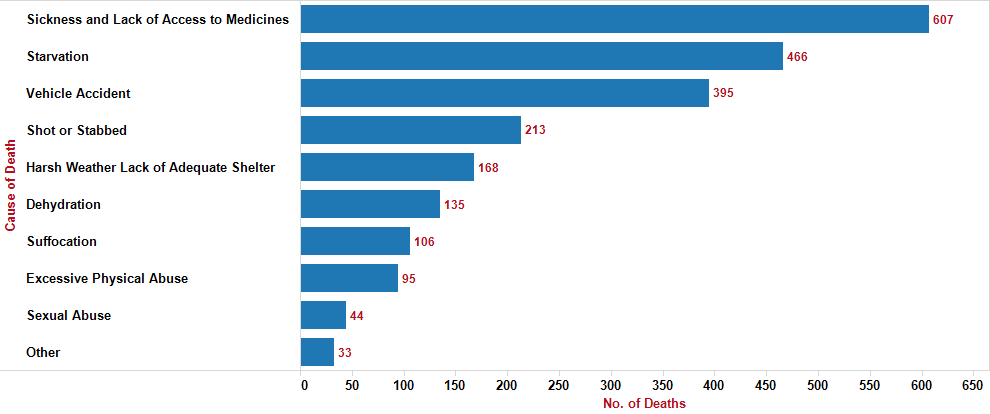

Figure 2: Contributing Causes of Death

Further, many of the deaths were reported to be at least in part due to preventable reasons. Access to medicine, food, water and shelter are an omnipresent contributing cause of death in the eastern tier of Africa, which indicates a need for services to cater to the humanitarian needs of migrants and refugees on the move. The large numbers of deaths reported in the Sahara Desert and on the roads in between populated areas confirm that the lack of access to life-sustaining goods and services can be lethal to populations in fear of detention and deportation to their countries of origin.

The 4Mi data offers a deeper but still incomplete picture of the lethal threats migrants and refugees face. With increased monitoring on the road, a clearer picture may be gleaned: a picture that may reveal the journey across the Sahara may be just as lethal as the journey across the Mediterranean.

Note: This article originally appeared on the RMMS Horn of Africa website.