An estimated 1.6 million Venezuelans have left their country since 2015, and about five thousand were departing every day as of the end of July 2018. The Venezuelan exodus is the largest forced displacement in Latin America’s history, and is starting to resemble the Syrian refugee crisis. More than 6.3 million people have fled Syria since 2011, in what has been the largest forced migration crisis since the Second World War.

These two situations, in which people ultimately face a denial of basic human rights in their homelands and are therefore compelled to flee have been increasingly compared in terms of volume of the exodus. We take this comparison a step further by contrasting the destination options that people fleeing Venezuela have with the options Syrian refugees have. This examination highlights how migration and asylum policies and treaties in Latin America differ from those in the Middle East-Europe region, and how in both cases a mass displacement of people has ignited more restrictive border controls.

The main difference between these two situations, aside from the fact that the Syrian exodus predates the Venezuelan one by several years, is what ignited them. The millions of people who have fled Syria have done so because of an on going, violent, geopolitical conflict that has caused much of the country to be unsafe. Venezuelans on the other hand, have been fleeing because their country is experiencing an economic meltdown that led to shortages of food and of medical supply. While Venezuelans have not had to endure a brutal war, they have faced an unsafe environment in their country; the violent crime rate in the Venezuela is amongst the highest worldwide, and repression by state authorities, including mass arrests and extrajudicial killings, is on the rise.

Top Destinations

In both the Venezuelans’ exodus and the Syrians’ – as well as any other forced displacement – distance, visa restrictions and cost of travel are among the main factors influencing the destination of people fleeing. The top destination of Venezuelans and Syrians has been a neighbouring country: Colombia and Turkey, respectively. The number of Venezuelans registered by Colombian authorities jumped from 48,714 in 2015 to more than 870,000 as of July 2018, while Turkey registered a similarly sharp increase of Syrian arrivals between 2013 and 2016.

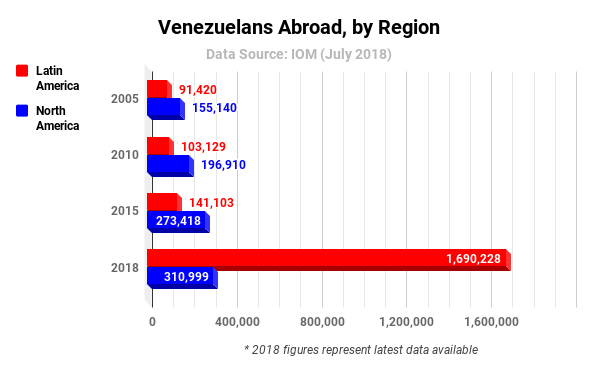

At the same time, there have been significant increases of Venezuelan populations in other Latin American countries, including Peru, Brazil, Ecuador, Chile and Argentina as well as in Panama and the Caribbean. The number of Venezuelans in North America and in Spain has also been rising, but 90 per cent of the Venezuelans who’ve fled their country in recent years have remained in Latin America.

Amongst Syrian refugees, about 89 per cent have stayed in the Middle East, mostly in Turkey, Jordan and Lebanon. These trends reflects not only visa restrictions and travel cost, but also the desire of most displaced people to stay close to home, as previously identified by the Pew Research Centre in a 2015 survey.

Right to Stay

A key difference between the Syrian and Venezuelan flight involves the legal measures each group has been using to obtain the right to stay in host countries. From the start of their exodus, Syrians arriving in other countries have been granted protection in accordance with the United Nations (UN) Refugee Convention, which defines as refugee anyone who has been forced to flee his or her country because of war or persecution.

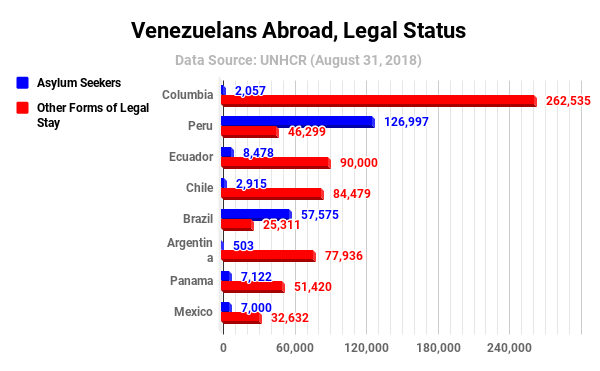

For Venezuelans, the situation has been different because the UN Refugee Convention does not recognize fleeing an economic meltdown as a cause for seeking refuge. Since the Venezuelans exodus began there have been debates in host countries and in the international community as to whether Venezuelans should be considered economic migrants or refugees. So far, the Venezuelans have mostly avoided the asylum system. While the vast majority of Syrians fleeing used the asylum system to gain residence permits in host countries, only about 20 per cent of the Venezuelans that fled their country have applied for asylum.

Instead, Venezuelans have relied on national and regional legal frameworks. The governments of Colombia, Peru, Ecuador and Brazil created a special mechanism to provide Venezuelans with immediate temporary residence permits, and Chile made available a ‘Visa of Democratic Responsibility’ for Venezuelan citizens. The Argentinian and Uruguayan governments have been granting Venezuelans legal residence based on the MERCOSUR Residency Agreement, a regional treaty that provides citizens of signatory countries the right to reside and work for a period of two years in other signatory countries. Mexico has been accepting Venezuelans based on the Cartagena Declaration, a regional treaty that expands the criterions on who should be granted protection beyond what is stated in the UN Refugee Convention to include people who are affected by developments such as economic decline or food insecurity.

Familiar Trajectory

In 2016, a Migration Policy Institute report described migration laws in Latin America as “heavily anchored on the respect of human rights, the principle of non-discrimination, and the understanding that crossing a border should not necessarily constitute a loss of rights,” and in March 2018, the UN refugee agency applauded countries in Latin America that introduced alternative legal stay arrangements for Venezuelans.

But in recent months, as the Venezuelan exodus intensified, the approach of Latin American countries towards Venezuelans has begun to be a little less welcoming. Top destination Colombia was the first Latin American country that expanded its border control efforts to halt the arrivals of Venezuelans. Brazil has sent troops to safeguard the border and in Brazilian border towns there have been protests and even mob attacks against Venezuelans. Peru and Ecuador enacted new immigration measures requiring Venezuelans to present a valid passport to enter the country.

These developments, in which countries that were initially welcoming adopt a more restrictive approach as the number of people arriving increases, happened in the Middle East as well. The main host countries of Syrian refugees – Turkey, Jordan and Lebanon – followed a similar trajectory as the Syrian exodus evolved, according to a 2017 report by the Refugee Studies Centre: all three countries had relative openness to Syrians when the crisis began in 2011, and then gradually increased restrictions. Turkey, which had an open door policy for Syrians, automatically granting those that arrived temporary protection status, recently completed the construction of a barrier wall along its border with Syria in an effort to prevent new arrivals; Jordan decided to close its border with Syria for security reasons, and in Lebanon there have been mass evictions of Syrian refugees.

As Latin American countries became less welcoming and violence and persecution of political opponents became more widespread in the country, the people fleeing Venezuela have increasingly turned to the international asylum system. Over 117,000 asylum claims from Venezuelans have already been filed in 2018, surpassing the total number of claims made in all of 2017, according to UN High Commissioner for Refugees. The number of Venezuelan applying for asylum is likely to continue growing, in particular also if countries further restrict other forms of migration.

Perilous Migration Routes

The increasing border controls of Latin American countries have also increased the risks for Venezuelans fleeing their country. Sex trafficking of Venezuelans who’ve fled their country is particularly rife along Colombia’s northern borders where criminal gangs and guerrilla groups are active, according to a recent report by the Colombia-based Ideas for Peace Foundation, and authorities in Spain have arrested members of two transnational networks sexually exploiting Venezuelan women and girls. Venezuelans that opt to go beyond neighbouring countries further south in the continent are “at times putting their lives at risk,” according to UNHCR.

The dangers of irregular migration routes are quite familiar to many Syrians, particularly those who left the Middle East. There were very few legal pathways for Syrians to reach the European Union, so the nearly one million Syrian asylum seekers that were registered in the EU between 2012 and 2017 used smugglers to get to Europe, often risking their lives.

Maintaining legal and safe pathways for Venezuelans to reach safer countries was one of the main topics of discussion in a summit of Latin American foreign ministers, which took place the first week of September in Ecuador. The summit did not yield a breakthrough, but the leaders did agree to allow Venezuelans leaving their homeland to enter their countries even if their travel documents have expired. The discussions continued the following week in a special meeting of the Organization of American States (OAS) that aimed to coordinate a regional response to the Venezuelan crisis. Following that meeting, OAS Secretary General Luis Almagro said, “No country can face this wave of migrants and refugees in isolation. The approach must be collective following the principle of shared responsibility.”

But Latin American countries and the international community have yet to establish a common policy in regards to the growing number of Venezuelan refugees and migrants.

And as this exodus continues, the Venezuelans fleeing – just like the Syrians refugees – may have fewer and fewer safe and legal destination options.