The following essay was originally compiled for the Mixed Migration Review 2021 and has been reproduced here for wider access through this website’s readership.

The essay’s author Chris Horwood is a migration specialist and co-director of Ravenstone Consult.

South-South migration is a key facet of mixed migration. Many of the movements in the Global South feature people of different categories and statuses moving together as part of the mixed migration phenomenon. The policy implications are many and far-reaching.

Even though more people migrate—be it regularly or irregularly, voluntarily or not—within the Global South (around 37 percent of all migrants) than from the Global South to the Global North (around 35 percent), most international discussion, socio-political angst, and media focus is on South-North migration. Part of the reason could be the predominance of academics, analysts and migration institutions based in the Global North, coupled with the somewhat fevered presentation of migration as a problem in the North, which is far less evident in the South, despite, as this essay will show, the huge differences in refugees’ and migrants’ experience of mobility there.

Any re-thinking of mixed migration, therefore, needs to focus on the key characteristics and dynamics of mixed migration in the South. By disaggregating the groups that make up mixed migration in the South, the prevalence and salience of all forms of mobility in the Global South become clearer.

A focus on South-South migration (SSM) is even more pertinent and timely, since proportionally, migration looks set to increase across all categories in the South, presenting both challenges (e.g. migration management, refugee hosting) and opportunities (e.g. the potential contribution of migration to regional economic development). This demands a re-think of our focus and emphasis: shouldn’t SSM and displacement take centre stage of global mixed migration analysis and policy debate, replacing the disproportionate—and often negative—focus on the lesser phenomenon of South-North migration? This essay explores the dynamics and dimensions of mobility in the Global South: its characteristics, prospects, and policy implications.

The mobility story of the South is neither even nor heterogenous. Embedded in the global figures of migration trends (currently 281 million people, 3.6 percent of the world’s population, are on the move) are huge differences between mobility profiles in Asia, Africa, Latin America, and Oceania. This is particularly true of Asia, which has more international migrant stock in absolute terms (almost 86 million) than Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, and Oceania combined (see Graphic 1). High levels of labour migration to the oil-rich states of the Gulf are also part of the South-South mobility profile.

While SSM is more prevalent than South-North migration in the Global South, North-North migration is very dominant in North America and Europe. Furthermore, migration transition theory suggests that whether the movement is South-South or South-North, populations will continue to migrate to higher wage-earning countries up to a threshold level of per capita earnings in the country of origin (roughly PPP$5,000–6,000 in 2014).

On current economic projections and expectations, for many countries in the South this would mean increasing numbers of people will continue to leave as economic migrants for decades to come, not only traveling from South to North but also within the South.

Source (adapted) and credit: IOM

A clear commonality between the geographical regions of the South is that regional mobility overwhelmingly originates from states within the region, as SSM.

Not surprisingly, in terms of economic migration, the normal general trend is of movement of people from lower-income to higher-income countries, whether the movement is from South to North, within the South, or within the North, conforming to migration transition theories based on the original thesis of human geographer Wilbur Zelinsky.

Beyond migrant stocks

To get a fuller picture of complex flows, mixed migration, and displacement, we need to look beyond migrant stock figures. In particular, if our interest is related to vulnerability and rights’ protection, it is relevant to establish where refugees reside; where the largest displacements (prompted by conflict, disasters, and climate change) are occurring; where internal migration is most prevalent, often as rural-urban movements leading to increasing urbanisation; where Covid-induced reverse migration recently took place; and where human trafficking is reckoned to be most prevalent. Additionally, we need to understand the scale and scope of the uncounted irregular migration and its trends in the South and consider the level and implications of involuntary immobility. When focusing on migration in the South we need to recognise that both quantitative and qualitative data is less widely available than in the North and that there is a higher degree of invisibility of some aspects of SSM. This means that we might even underestimate the scale of SSM, where movement may be nested within other socioeconomic phenomena such as urbanisation.

Refugees and asylum seekers

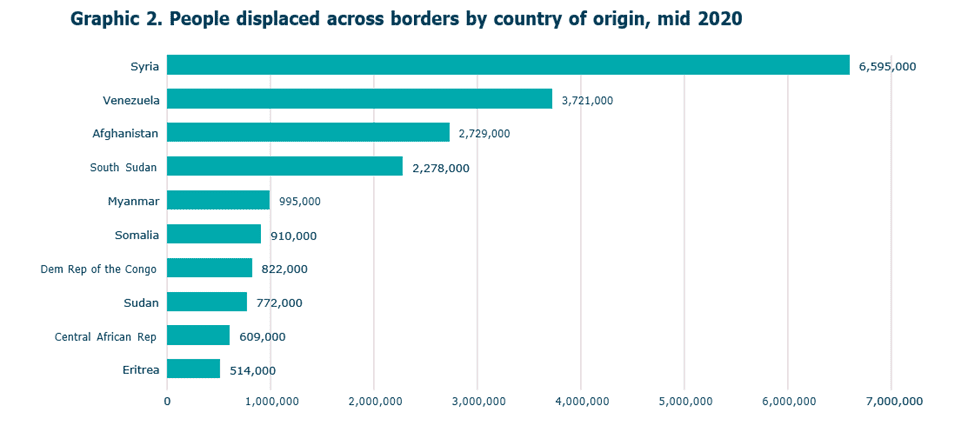

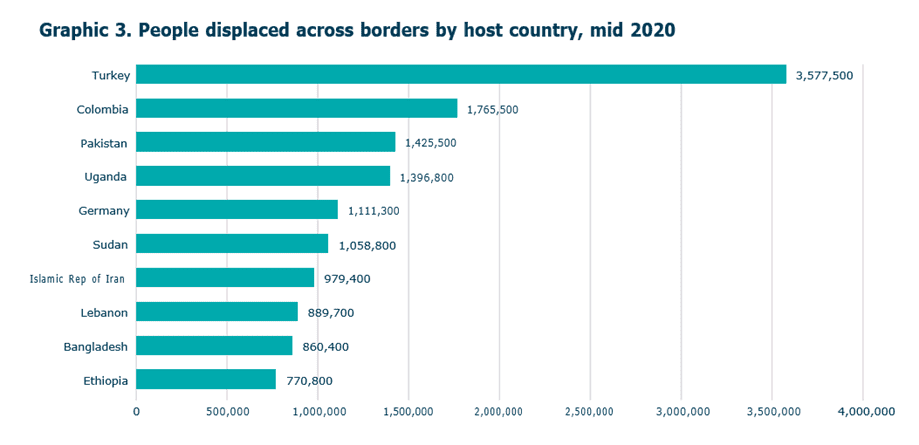

As of mid-2020, UNHCR stated that the total number of people forcibly displaced across borders had reached a total of 34.4 million. This number includes: 20.7 million official convention refugees, 4.1 million asylum seekers, 5.7 million Palestinian refugees under UNRWA’s mandate, and 3.9 million Venezuelans displaced abroad. Many of these have been displaced for years or even decades, but 11.2 million were newly displaced in 2020. The top ten ranking nationalities displaced (excluding Palestinians) are shown in the chart below (Graphic 2). The companion chart (Graphic 3) clearly shows that almost all those displaced internationally are hosted in the Global South. The only exception is Germany, whose ranking rose significantly after it took in over a million (mainly Syrians) during 2015/2016 when large numbers of refugees and migrants arrived in Europe and moved further north, often to Germany. According to UNHCR figures, “developing countries host 86 percent of the world’s refugees and Venezuelans displaced abroad. The Least Developed Countries provide asylum to 28 percent of the total.” In the current climate of strengthening borders, externalisation deals, conditionalities in aid agreements, and pushbacks (often illegal under international law), “fewer potential refugees reach countries ready and capable to recognize their status”. New conflicts and political turmoil continually add to the de facto hosting of those fleeing events in the South, such as the Tigray crisis in Ethiopia and violence in the Central African Republic.

Source: 2020 UNHCR

Source: 2020 UNHCR Source: 2020 UNHCR

Source: 2020 UNHCR

Forced internal displacement

The director of the world’s leading displacement tracking organisation, the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) said in early 2021: “Conflict, violence and disasters continue to uproot millions of people from their homes every year. Never in IDMC’s history have we recorded more people living in internal displacement worldwide than we do today.” There were 55 million internally displaced people (IDPs) across the world at the end of 2020; 48 million as a result of conflict and violence, and 7 million as a result of disasters. Those displaced by conflict and violence were situated in 59 countries and territories as of early 2021, all in the Global South. Equally, with the exception of those displaced by bushfires in 2020 in the United States, all disaster- related displacement globally occurred in the Global South. Graphic 4 shows the increasing predominance of weather events over geophysical events as the cause of displacement. Together, this level of forced movement and disruption represents a significant proportion of global mobility.

Source (adapted) and credited: GRID 2021. IDMC (Part 2).

Source (adapted) and credited: GRID 2021. IDMC (Part 2).

Urbanisation—internal movement

Urbanisation typically represents rural-to-urban movement, although it may also occur between urban centres, normally towards larger metropolises. Globally, the level of international migration is dwarfed by levels of internal migration which, when not related to disaster or conflict, is predominantly rural-to-urban movement. In 2021 the International Organization for Migration (IOM) estimated the global total of internal migrants at 763 million, almost three times the number of international migrants. Even a proportion of internal displacement related to conflict and disasters becomes de facto urbanisation in some cases. China is still in the midst of its urban transition, dominated by rural-to-urban migration; an estimated 14 percent of the population of 1.4 billion is engaged in such internal movement. China’s internal migration, like India’s, represents a significant proportion of the global total. In the Global South, migration drivers are various, but are generally linked to limited livelihood opportunities and the diminishing ability in rural areas to achieve desired economic, social, health, and educational outcomes. Economic and livelihood needs are increasingly linked to overpopulation, resource competition, and productivity, and are exacerbated by changing environmental conditions. Here we distinguish economic drivers of mobility from the political or security related drivers that force people to flee their homes as IDPs or, when they move across borders, as refugees. Relatively speaking, migration in the Global South is dominated by internal migration, while migration in the Global North is more international, which could be explained by the fact that international migration usually requires more substantial resources.

Many middle-to-upper income countries in Latin America, North Africa, and the Middle East have already experienced high levels of urbanisation that continue, but at a slower pace. In many low-to-lower-middle income countries of the Global South, the majority still live in rural areas, but the situation is changing rapidly with urbanisation today primarily taking place in parts of Asia and the Pacific and Africa (see Graphic 5). Ninety percent of projected urban population growth will take place in African and Asian countries. Africa, whose population is projected to double between 2020 and 2050, has the highest rate of urbanisation of all continents and two thirds of that population growth will be absorbed by cities. It is expected that over a third of the projected global urban growth between now and 2050 will occur in just three countries: India, China, and Nigeria, with India adding 416 million urban dwellers, China 255 million, and Nigeria 189 million. To the extent that current and future urban growth results from the internal mobility of hundreds of millions of people from rural to urban areas— rather than from “natural” population growth—this too is occurring and will continue to occur overwhelmingly in the Global South.

Source (adapted) and credit: Our World in Data.

Covid-induced reverse migration

During 2020 and into 2021, many millions of migrant workers joined modern history’s largest “reverse migration” phenomenon. Predominantly urban-to-rural and domestic, return migration was driven by the effects of lockdowns, curfews, workplace closures, suspension of salary and other earnings, quarantine, fear of family separation for an unknown period, and fear of contagion. It affected millions of workers throughout less developed and middle-income countries in East Asia, South Asia, Africa, the Middle East and the Americas in the Global South. It also manifested to a lesser extent in Global North countries such as Italy, the US, and France, where far more government safety nets and economic security measures were provided. In the South, return migration not only helped spread the pandemic to rural areas but generated hardships and vulnerabilities for individuals and communities. The urban exodus in India was dramatic and much publicised. Somewhere between the official government figure of 10 million and as many as 60 million migrant workers returned home. International reverse migration involving Indians was also huge in scale. In Kerala state, for example, more than 12 million returned from the Gulf States between May 2020 and March 2021.

In Peru, an estimated 200,000 people attempted to migrate from Lima to their home villages after the country imposed an extended lockdown in late April 2020. Even some Venezuelan refugees and migrants in Peru returned home during 2020, as they did from other Latin American countries. Some reports suggest that as of late 2020, up to 130,000 Venezuelans had returned to Venezuela because of the Covid-19 pandemic and its economic impact. Similar situations were reported in Uganda, Kenya, Morocco, South Africa, Zimbabwe, and numerous other places in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Human trafficking

Given the hidden nature of human trafficking, understanding the full scope and scale of the issue is problematic and further complicated by definitional aspects. Contemporary analysis of human trafficking employed by relevant agencies includes modern slavery, which covers a set of specific legal concepts, such as forced labour, debt bondage, forced marriage, other slavery, and slavery-like practices. Human trafficking may or may not entail crossing borders and does not always include mobility at all. According to 2017 data compiled by a collaboration between the International Labour Organization (ILO) and the Walk Free Foundation, in 2017, 40.3 million people were in situations of modern slavery, including 24.9 million in forced labour and 15.4 million in forced marriage.21 Extracting from these figures those that involve mobility and those that do not is not practical but the relevant observation for this essay is that the vast majority of the world’s forced labour occurs in the Global South and involves people from the South. North-North human trafficking exists, as does South-North trafficking, but the majority is South-South. It includes high levels of often-hidden (involuntary) human mobility and is associated with severe human rights violations. Graphic 6 below shows the global sexual and labour exploitation distribution of detected trafficking victims, who, because of the paucity of confirmed data, represent just a small fraction of the full extent of human trafficking.

Source (adapted) and credit: UNODC

Source (adapted) and credit: UNODC

Irregular migration

Like human trafficking, irregular migration is difficult to track as it occurs intentionally outside the regulatory norms of countries and is typically clandestine. In terms of irregular flows, the phenomenon refers to the movement of people in an undocumented fashion, and in terms of irregular migrant stocks it refers to migrants who reside in a country irregularly or undocumented. Migrants can go in and out of irregularity as laws and policies change (for example as a result of the regularisation of people with an irregular status) and the phenomenon is worldwide, occurring in all continents both in the Global North and South.

Some estimates of stocks suggest that between 3.6 million and 5.5 million irregular migrants reside in Europe, and the latest figures from the US suggest around 11.3 million undocumented migrants live there. Elsewhere, available information and data is fragmentary, although in 2009 the UN reported the number of irregular migrants globally to be around 50 million. If we use this figure and extrapolate from 2009 to the current date at the same growth rate as global migration, we find there may be around 65 million irregular migrants in 2021.

The estimated numbers of irregular migrants in other destination countries in the Global North, such as Australia, New Zealand, Japan, and Canada are very low, but in Russia they are said to number at least one million, mainly from the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). Added together, the Global North may account for around 19 million of the 65 million irregular migrants globally, under 30 percent of the total stock. Again, although less publicised, if the numbers, estimates, and assumptions made here are correct, the majority (at least 70 percent) of irregular migrants reside in countries in the Global South.

The millions of individual stories behind these statistics in the South include the untold tales of irregular migration: journeys between countries in sub-Saharan Africa, such as crossings into South Africa from neighbouring states and from the Horn of Africa and much further afield (China, Pakistan and Bangladesh); Egyptians and Tunisians going to Libya; Bolivians and Haitians going to Brazil; Chinese migrating irregularly within Asia, including into Japan and some further into the Caribbean; Indonesians going to Malaysia; Cambodians to Thailand; Comoros islanders to (French) Mayotte; Ethiopians to Yemen and Saudi Arabia; Central Americans into Mexico; and countless other multi-directional journeys. Data is sparse and hard to come by as irregular migration flows do not appear in official census data and require dedicated data collection, through monitoring and surveys. Depending on factors such as interest, resources and access, some mixed migration routes are better monitored than others, and some destination or transit countries have borders that allow for more reliable counting. This is particularly true of coastal borders, such as Yemen’s before its current war, and those of European states and Malaysia, among others. This inconsistency means that data and knowledge on the volume of irregular migration remains patchy and ad-hoc: well-documented in some contexts, only partially available or completely absent in others. A global overview of irregular migration volumes is thus non-existent, omitting a substantial aspect of global migration, particularly in the Global South.

Voluntary and involuntary immobility

The vast majority of people in the world do not migrate at all but rather stay put, either voluntarily (i.e., they do not aspire to migrate) or involuntarily (as explored below). To avoid a “mobility bias”—that is to say, focusing on migration while most of the world’s population never migrates—to reduce the risk of overlooking the countervailing forces or drivers that prevent people from migrating, those who are involuntarily immobile should be taken into account, not least because, again, they are almost entirely in the Global South.

Applying the aspiration/capability model for migration decision-making and outcomes, involuntary immobility can be broadly defined as, having the aspiration (or need, in cases of pressing factors forcing people to flee) but not the ability to migrate or flee. This is not to be confused with “acquiescent immobility”, where there is neither the capability nor the aspiration to migrate. There are also those who, having departed, become immobilised before they reach their hoped-for destination. Gallup has been asking people around the world about their migration aspirations and actual plans for some years. As Graphic 7 below illustrates, the latest data (2015-2017) shows a rising trend almost everywhere in the desire to migrate, but the proportions are far higher for most regions of the Global South. Sierra Leone was the highest with 71 percent of its adult population desiring to move permanently. Asia is a notable exception within the Global South: here the desire to migrate permanently is lowest.

Note: Figures represent percentage who would like to move if they could. Source: Gallup

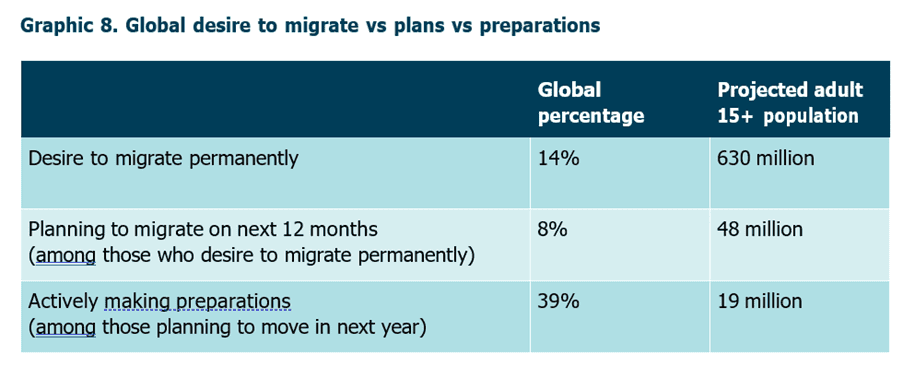

When aspirations are compared to actual plans and preparations to migrate (see Graphic 8 below) the number of those actively preparing to move in the coming year (19 million) is about 3 percent of the total of those desiring to migrate (630 million). In the “mobility gap” between 630 million and 19 million are many millions who for various reasons are unable to migrate or have not started to plan their migration yet, let alone taken active preparations. The bulk of these are in the Global South. Although we should resist drawing too many conclusions from this data, it is useful as an indication of potential levels of involuntary immobility, even though many may, for a variety of reasons, not yet have started planning, and this would not necessarily make them involuntary immobile. However, in cases where reasons to migrate for significant numbers are compelling but where capability is severely lacking, humanitarian or political crises may ensue, with potential regional consequences.

As the impact of climate change combines with other threats, the risk of such situations developing in the future grows. With states in the South being most affected by, and least prepared for or protected from, the impact of climate change, the numbers of future involuntarily immobile migrants in the South may be substantial and far outnumber any in the North.31 New political events such as the withdrawal of foreign forces from Afghanistan in mid-2021 and the resurgence of the Taliban also threaten to create as yet unknown numbers of involuntarily immobile people and prompt cross-border flight.

Based on surveys conducted between 2008 and 2010 in 146 countries. Source: Gallup

‘Migration states’ of the Global South

The above overview of global aspects of (mixed) migration shows how the different forms of migration that, taken together, characterise societies across the South occur mainly between states of the Global South. While the North still dominates in terms of South-North economic migration (with numbers increasing through additional family reunifications etc.), in the South there is such a diversity of movement, displacement, and migratory situations that the term South-South migration ends up oversimplifying and generalising a complex situation, one where “it would be challenging to find a single country that was not simultaneously, to varying degrees, a country of origin, destination, transit, and return for migrants.” Additionally, “it also has powerful political implications, in that it helps counteract the rhetoric that would see migrants ‘invading’ the ‘Global North.’” It also suggests that the policy discourse should no longer take place predominantly in the North.

The term “migration state” has normally been used to describe advanced economies dependent on migrant labour as a permanent feature of post-war globalisation. But here we see states of the South are not only “migration states” in terms of labour migration but also in all other categories of movement and displacement, formal and informal, regular and irregular. In other words, mixed migration is a key characteristic of mobility within, through, and between many states of the Global South.

Lessons for the North

In dealing with large-scale displacement and migratory movement, the South may offer some important lessons to the North on how to manage mobility and be more creative in responding to the influx of refugees and migrants.

In responding to the exodus of around 5.5 million Venezuelans since 2014, Latin America is seen as a laboratory for innovative practices and flexible requirements for the regularisation of displaced Venezuelan refugees and migrants hosted in numerous cities and towns in Columbia, Peru, Ecuador, Chile, Brazil and Argentina. By 2020, these countries had issued residence permits or regular stay status to more than 2.4 million Venezuelans, with more than 800,000 additional asylum or residency cases pending.36 By contrast, most of those Venezuelans who fled to the US are not permitted to present themselves as migrants but only as asylum seekers and, as of late 2020, about a third (around 105,000 people) have pending asylum claims, with only a minority (about 16,000) recognised as refugees.

In the Middle East, the displacement of Syrians resulted in almost six million refugees being absorbed and hosted by neighbouring Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey, Iraq, and Egypt, countries where they now make up a large proportion of the total population—in Lebanon they comprise almost a quarter. Jordan (with a total population of 10 million) already hosted an estimated three million Palestinian refugees before it took in almost a million Syrians and through the Jordan Compact agreements allowed over 80,000 Syrians to have work permits to work in specially created economic zones. Meanwhile, the European Union (population 450 million) experienced policy panic and political disruption after a million Syrians entered in 2015/2016.

In Uganda, refugees—mainly from South Sudan and DR Congo—enjoy most of the same rights and access to jobs and services as Ugandan citizens and the country is seen as a global leader in implementing an integrated approach to refugee management.

There are many other examples of refugee hosting and integration as well as de jure or de facto integration of migrants (regular and irregular) in the South, but also some notable exceptions. For example, violent xenophobic reactions to refugees and migrants in South Africa so specifically targets Africans that it has been dubbed “Afrophobia”, and its periodic public outbreaks are often lethal. In Kenya, the repeated government denouncements of hundreds of thousands of Somali refugees as posing a terrorist/security threat lies in ambiguous contrast to its hosting of Somalis for three decades. Another example is Malaysia’s well recorded history of xenophobic reactions to foreigners from elsewhere in Asia and from Africa, which were exacerbated during the Covid-19 pandemic. There are more examples, but despite evident discrimination and human rights abuses or workplace exploitation, and despite dire conditions and prospects for millions of camp refugees or internally displaced people facing protracted limbo, the Global South as a whole tolerates extensive multicultural integration and migration without it developing into political crisis. By contrast, far smaller levels of migration and displacement (proportionally and in absolute terms) are treated in the North almost as existential threats and lead to significant socio-political crises resulting in harsher immigration regulations and more fortified and militarised frontiers.

Increasing regional cooperation and process

Increased economic cooperation between states and regions in the South may be key to a greater capacity to absorb and integrate current and expected future mobility. Mercosur in South America (also known as the Southern Common Market), the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, the Economic Community of West African States, and the Southern African Development Community, not to mention the African Union itself with its “2063 agenda” and its vision of free movement across the whole continent, are strong examples of regional cooperation in the South. Enhanced regional cooperation and integrated approaches that create a stronger economic and protection environment can build greater support for migration and asylum and harness the dividend and dynamism mobility can bring to host countries.

Disconnect in government in the South between migration and other policy areas, including development and employment, and a lack of coordination between different levels of governance (local, national, bilateral, regional, etc.) could be remedied through burden-sharing agreements, bilateral labour migration agreements, or increased regional South-focused consultative processes such as the Regional Conference on Migration (Puebla Process), the South American Conference on Migration, the Abu Dhabi Dialogue, and the Colombo Process.

There are other long-standing dialogues in the Global South that can be harnessed for important development in relation to mobility. What is now known as South-South cooperation, for example, derives from the adoption of the Buenos Aires Plan of Action for Promoting and Implementing Technical Cooperation among Developing Countries by 138 UN Member States in Argentina, in 1978.

The lesser-known United Nations Office for South-South Cooperation (UNOSSC) was established as early as 1974 by the UN General Assembly to promote, coordinate, and support South-South and triangular cooperation globally and within the United Nations system. UNOSSC and IOM signed a memorandum of understanding in 2019 to cooperate in areas of mutual concern and enhance the effectiveness of their development efforts including supporting the UN Network on Migration and the implementation of the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration. Cities, and more active mayoral roles are already showing potential in addressing migration, displacement, and refugee issues in both the North and the South with, amongst others, new initiatives such as the Mayors Migration Council.

No time to lose

When considering the current global context and current and projected factors affecting mixed migration flows, it seems clear that the policy challenges and opportunities of the inevitable rise of SSM require deeper reflection and action plans in the South. Consider the implications on mixed migration and SSM of factors such as:

- Population growth and regional differences in population growth (especially Africa and Asia)

- Asylum space: reduced settlement options and hardening of attitudes in countries of the North blocking large movements

- Location of major disasters

- Location of conflicts and war and insurgency

- Continued growth of urbanisation (especially in Africa and Asia)

- Entry of women into workforces and the demand for labour (especially in Africa and Asia)

- Climate change and related environmental stressors (where will this hit hardest and cause most SSM)

- Production transformation: AI and automation and the potentially reduced need for migrant workers in the Global North

- Governance: inability to control population movements or implement polic

- Evidence-based economic theories of migration (migration transition theory), suggesting that as development continues more rather than fewer people in the South will seek to migrate.

These factors are pressing and indicate that there is no time to lose. Greater recognition is needed by countries in the North and the South that immigrant integration is not only a policy domain for “rich” countries. SSM is, and can continue to be, an important development phenomenon for the South but should not be encouraged simply because it may act as a vent for potential South-North migration. However, behind the Global North’s support to regional migration dialogues, regional economic communities, and the implementation of regional free movement protocols in the Global South seems to lie the increasingly explicit objective that regional mobility will promote economic development in the South and reduce irregular movement to the North. The thrust of recent (post-2015) support and capital transfers to the South from the North in some regions (such as the EU Trust Fund and the EU’s new €79.5 billion Global Europe fund with their migration-related conditionalities) has increasingly focused on stemming unwanted irregular migration. Nevertheless, a harmonised approach to migration and displacement often remains elusive.

While this overview analysis highlights high levels of mobility, the discussion needs to be understood in a context where the vast majority of people globally (an estimated 96.5 percent) are residing in the country in which they were born. However, in view of the predominance of all forms of mixed migration in the South, some critical questions emerge: Should current and future SSM be treated as a threat or an opportunity? If as an opportunity, for whom? Migrants themselves, their host or origin countries, or countries in the Global North? How will SSM be allowed to develop? To what extent can SSM in all its forms be harnessed for development and maximised? (“South-South migration has the same potency to contribute to inequality, but also to reduce inequality—as the South-North migration.” What does migration in the South demand in terms of governance and policy developments, and how can the rest of the world and global institutions support this? Finally, what do we miss by downplaying South-South movement? What learning opportunities are missed from the South when, in contrast to the Global North, it adapts to, absorbs, and manages large numbers of people on the move with a fraction of the dilemmas and crises that face the North?