This article highlights shifts in mixed migration on the Central Mediterranean route towards Italy, in numbers, but mostly in terms of nationalities and routes, and tries to understand what these trends are telling us about the broader mixed migration dynamics currently ongoing in the Mediterranean region and beyond.

A significant increase in arrivals

In 2021, 66,770 people arrived in Italy by sea. While still much lower than in the years 2014-2017, with well over 100,000 arrivals per year, this was a considerable increase on 2018-2020 (arrivals numbers 23,370 in 2018; 11,471 in 2019, and 34,154 in 2020), despite the Covid-19 related restrictions on movement.

Changes in origin of arrivals: Asians and North Africans instead of sub-Saharan Africans

Besides the number or arrivals, what’s noteworthy when looking at trends from 2016 onwards, are the countries of origin of the arrivals.

The table below, with the top 5 nationalities among arrivals in Italy, shows the shift in where people are coming from. In 2016, the top 5 was exclusively from sub-Saharan Africa, with particularly large numbers from Nigeria and Eritrea.

In 2017, 4 of the top 5 nationalities originated from West African countries, with the exception of Bangladeshis.

However, from 2018 onwards, this starts to change. Nigeria does not feature any more (e.g. less than 700 arrivals in the whole of 2021), and, from 2019, neither does Eritrea (although the number of Eritreans arriving in Italy increased in 2021, to over 2,000, possibly related to the conflict in the Ethiopian Tigray region, which hosts large numbers of Eritrean refugees).

Additionally, in 2018 Tunisia becomes the number one country of origin, and Algeria, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Egypt feature as other important countries of origin from 2018–2021. With the exception of Côte d’Ivoire, the decrease in the number of West Africans arriving in Italy is quite striking. In 2021, the only other West African country featuring in the top 10 is Guinea.

What also stands out, and is a new trend, is the relatively large numbers (compared to previous years) of Iranians (3,793, entering the top five nationalities) and Iraqis (2,514) arriving in Italy in 2021, nationalities that were previously using the so-called Eastern Mediterranean route between Turkey and Greece (see below).

Figure 1: Top 5 nationalities of sea arrivals from 2016 – 2021. % refers to proportion of the total number of all arrivals in Italy by sea.

Source: Italian Ministry of the Interior, cruscotto statistico

Changes in departure countries and sea routes

To better understand what is happening with regard to the changes in arrivals in Italy, it is worth looking back at the routes that are being taken. Have these changed too? It turns out that the primary country of departure for people arriving in Italy has been indeed changing in recent years. This is a result of a number of factors such as broader migration management dynamics, cooperation between Europe and its neighbours, economic and political conditions in origin and transit countries, and other factors that close or open other routes.

Tunisia as main country of departure

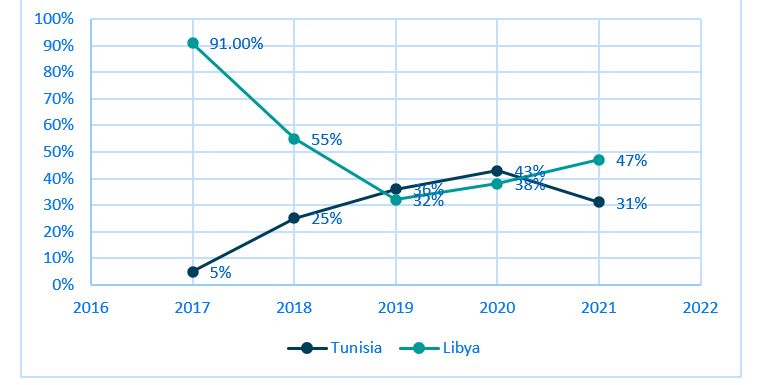

As shown in the graph below, in 2017 Libya as country of embarkation accounted for 91% of arrivals in Italy, and Tunisia only 4.5%. Things started changing in 2018, with Libya going down to 55% and Tunisia up to 25% and in 2019 Tunisia became the most common country of departure for people arriving in Italy, accounting for 36% of the arrivals, versus 32% who departed from Libya. This trend continued and further increased in 2020, with 43% of the total arrivals coming from Tunisia versus 38% from Libya. However, in 2021 when, as we saw above, there was a general increase in arrivals along the Central Mediterranean route, Libya became the primary country of departure once again, with 47% of departures, followed by Tunisia with 31%, which equals almost 20,000 people departing from Tunisia.

Figure 2: Sea arrivals in Italy, from Tunisia and Libya

Source: UNHCR Data Portal Italy

The key driver behind this dynamic is simply the increasing number of Tunisians leaving for Italy, as a result of an interplay of economic and social factors, further exacerbated by the Covid-19 crisis. As shown above, Tunisia has consistently been the primary country of origin among arrivals since 2018 and logically most of them leave from Tunisian shores.

However, the prominence of Tunisia as country of departure also helps to explain the Côte d’Ivoire exception, as the only West African country that remained in the top five of arrivals in recent years. Many Ivorians reportedly left Tunisia after having lived there for a few years. According to Tunisian migration policies, people from Côte d’Ivoire can enter Tunisia without a visa, and the number of Ivorians travelling to the country to work or continue their studies has been growing in recent years, becoming the largest refugee/migrant population in the country. Just like Tunisians, but compounded by racism and discrimination toward sub-Saharan Africans, many have been affected by the socio-economic crisis in the country, and decided to leave for Europe. At the same time, there are also reports of an increasing number of sub-Saharan Africans, including Ivorians, considering Tunisia as a better place from which to transit to Italy, as it is easier to access, and passage to Italy less risky than the route through Libya or between Morocco and Spain. Finally, this trend is also linked to the growing smuggling business in Tunisia, which, simultaneously, creates and responds to increasing demand for crossings to Italy.

The growing importance of Turkey

The other country that has become an increasingly important country of departure for Italy, since 2018, is Turkey. Departures went from virtually zero in 2017, to 12% of the total in 2018 and 18% in 2021. Most people travelling along this long sea route originate from Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan, which helps to explain the increase in these nationalities among arrivals in Italy and, more specifically, the relatively high number of Iranians in 2021. The growing importance of Turkey as country of departure does not come as a surprise when looking at the increasingly restrictive approach to border control and migration management adopted by the new Greek government since 2019, both at the land border with Turkey in Evros and in the Aegean islands, and the allegations of large-scale and systematic illegal pushbacks. In 2021, land and sea arrivals together in Greece were below 10,000, the lowest number in many years; since January 2021, only 813 Afghans, 237 Iraqis and 65 Iranians have arrived in Greece. This shows that the Greek government has to a large extent managed to close down the Eastern Mediterranean migration route. Unlike in 2017, when the claims of many commentators about a shift in movements from the Eastern Mediterranean route to the Central Mediterranean route were based on assumptions rather than evidence, this time the analysis of the data confirms a partial shift. This has not so much been a change in the route up until embarkation – people from Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iran, and Iraq are still travelling to the coast of Turkey – but in where the sea route is directed to from Turkey, namely to Italy instead of Greece.

This latest trend is also clearly reflected in the ports of disembarkation in Italy. The ports of the Southern region of Calabria, facing the Ionian Sea, have historically been the landing spots for arrivals from Turkey and Greece, while people embarking in North Africa generally land in the ports on the Mediterranean coast, in Sicily or closer to Sicily channel. As of October 2021 7,000 refugees and migrants had arrived in the Calabrian town of Roccella Ionica and neighbouring municipalities, which is three times more than the total in 2020.

Arrivals tell half the story: focus on interceptions

The analysis of the changes in countries of departure of those arriving in Italy explain some of the mixed migration trends and dynamics in the Mediterranean of the last few years. However, arrivals only tell part of the story. For a more complete picture, we need to also look at interceptions at sea, and how it differs per nationality.

Libyan interceptions

Interceptions at sea after departure from Libya increased after the memorandum of understanding signed in 2017 with Italy, which included significant funding and support to the Libyan Coast Guard, and has been regularly renewed ever since. Since then, the Libyan Coast Guard have been intercepting and returning many people to Libya: in 2019, 9,225 people were intercepted, an estimated 70% of all departures; in 2020, an estimated 47% of those attempting the crossing were intercepted (11,891); and in 2021, the estimated interception rate is around 50%, with almost 30,000 interceptions, the highest absolute number per year since the tracking of interceptions began.[1]

The above shows show us that when also considering attempted, but failed, crossings from Libya, movement along the Central Mediterranean was even higher in terms of numbers in 2021 than in previous years.

Figure 3: Estimated departures from Libya and Tunisia

Some nationalities are more likely to be intercepted than others

But beyond these numbers there is another element, something that is not widely reported on, which is the discrepancy between the main nationalities of arrival in Italy and the main nationalities of those who departed from Libya but are intercepted and disembarked in Libya. Among the primary nationalities departing from Libya and intercepted by coast guards are Sudanese, Bangladeshis and Malians. While Bangladeshis are the third nationality of arrivals in Italy, and therefore it makes sense to also see them among the main group of people intercepted, Sudanese and Malians are 11th and 16th in the list of arrivals by nationality in Italy. What this might suggest is that certain nationalities have a higher chance of being intercepted than others. While the data, in particular on the nationalities of those who attempted departures from Libya, remain sketchy, comparing the number of arrivals with the number of interceptions for the period January-October 2021 shows markedly different estimated interception rates of 71% for Sudanese and Malians (with both higher numbers of interceptions than arrivals in Italy), compared to 31% for Bangladeshis. One plausible explanation is that some nationalities are using better established smuggling networks – and are also paying more to smugglers – and therefore have a reduced risk of interception by the Coast Guard.

Interceptions in Tunisia

Official data and information about interceptions by the Tunisian Coast Guard are much more difficult to obtain. According to existing sources, interceptions went from approximately 4,000 per year in 2018 and 2019, to 13,500 in 2020. Though interceptions by the Tunisian Coast Guard are far less widely reported in media compared to Libya, this actually shows a similar interception rate: in 2020, approximately 50% of total departures from Tunisia were intercepted (14,685 persons made it to Italy from Tunisia in 2020).

According to the same source, interceptions during the first 9 months of 2021 went up to 19,500, versus 19,318 arrivals in Italy, thus maintaining the approximated interception rate of 50%. This reflects the intense cooperation between Tunisia, Italy and the EU to reduce irregular departures, with high-level meetings taking place to discuss cooperation on migration issues in both March and May 2021 and an EU pledge of 11 million Euro to address the so called root causes of migration from Tunisia and strengthen border management.

Data on nationalities of people intercepted and returned to Tunisia are not available so it is impossible to verify whether, as seems to be the case for Libya, some nationalities were disproportionately targeted during interception operations. However a quick search on news articles and other sources about interceptions seems to indeed indicate a disproportionally high number of sub-Saharan migrants and refugees intercepted, compared to Tunisians, even though the latter group leaves in much larger numbers (see for instance Agence France-Presse, Infomigrants and UNHCR).

What to make of all this?

A number of ongoing or emerging dynamics are highlighted through this analysis.

When it comes to countries of departure, Tunisia has become increasingly important. First of all, due to the political and socio-economic situation in the country, Tunisia has become itself a major country of origin, and this is likely to continue. In addition, Tunisia has become an important gate keeper for the EU, joining a long list of other countries such as Libya, Morocco, Egypt and Turkey, preventing irregular crossings of refugees and migrants who are either in transit towards the EU or, after having lived in the country for some time, decide to move on to Europe.

The analysis also shows that, increasingly, refugees and migrants who would previously enter the EU through Greece and the Balkans, are bypassing Greece, and using a sea route from Turkey to Italy. The most remarkable change in this regard in 2021 is the relatively high number of Iranians using this route, with 3,915 arrivals in Italy versus 65 in Greece. In the future, considering the current trends in the region, this route could increasingly be used by Afghans leaving violence, discrimination, and economic hardship after the Taliban take-over in August 2021.

We see that closing a migration route is possible to an extent (although at high moral and financial cost, and bringing increased risks for refugees and migrants involved), as has been the case for the Eastern Mediterranean route between Turkey and Greece. However, as the increase in arrivals in Calabria shows, it can be only a matter of time until people (re)turn to different – often already existing – routes.

The analysis of the interception rates by nationality shows the importance of reviewing not only arrivals but also departures and interceptions for a complete picture. It also shows different nationalities have markedly different chances of being intercepted. It is likely that some nationalities may be able to afford smuggling services that allow them to avoid detection by coast guards, while others do not. The crossing of the Mediterranean Sea is dangerous, but being “rescued” and returned to Libyan detention centres can be just as dangerous, as documented by several shocking reports over the years. In 2021, 20,000 refugees and migrants taken back to Libya went reportedly missing, most likely ending up in clandestine detention facilities, controlled by traffickers or local armed groups. An appalling and unacceptable situation and a stark and tragic reminder that behind all the numbers and trends presented in this article are individual human beings facing unimaginable dangers and inhumane treatment.

While the analysis of interception rates shows that at least some sub-Saharan African nationals seem to be more affected by interception (i.e. Malians), this analysis does not fully explain the very significant decrease in sub-Saharan African arrivals in Italy since 2018. This may be linked to a general reduction in movements along the migration routes through West Africa towards Libya, for example due to EU-supported efforts by Niger to stop movements north and, since 2020, due to Covid-19 related restrictions on mobility. The conflict in Mali and, more recently, in Burkina Faso, might also be a factor for the decrease of movements towards Europe, as the routes become more and more dangerous. To some extent, movements from West Africa to Europe may have shifted to the Atlantic route to the Canary Islands, which has seen a large increase since 2020. However, this is beyond the scope of this article and should be further explored.

Once more, this analysis of arrivals in the EU highlights the intense level of diplomatic, financial and logistical efforts that the EU and individual European countries are deploying into either protecting their borders, for example in Greece, or externalising border management to third countries, in case of Libya, Tunisia and, further down the route, Niger. It is notable that despite generally managing to reduce the numbers of arrivals (although there has been an uptick in arrivals in Italy in 2021), the overall approach still seems to be fuelled permanent political crisis at EU borders. As such, the approach remains heavily oriented towards the short-term objective of reducing numbers along every possible route, with little regard to the ever-increasing human cost and little sign of the creativity, innovation and political courage needed to develop a longer-term, more humane and sustainable approach to mixed migration towards Europe.

[1] The number of people who depart from Libya but never make it and pass away during the crossing, are not included in these calculations, as for migrant deaths it is not always known from which country they departed. Additionally, these interceptions rates do not include those who departed from Libya and arrive on Italian shores undetected. As such, these interception rates are estimates and not precise figures, but they do provide an indication of the extent of activity by the Libyan Coast Guard.