The following essay was originally compiled for the Mixed Migration Review 2019 and has been reproduced here for wider access through this website’s readership.

Whether they move irregularly or regularly, the global economy and labour markets are critical for migrants and refugees. Once they find sanctuary from the persecution or physical insecurity they left behind at home, their top priority is generally to obtain paid work. After all, poverty and lack of opportunities are among the primary mobility drivers of those in mixed migration flows. This essay outlines some global economic projections and explores their implications for people on the move.

Projected convergence

By 2050, global GDP will have grown by 130 percent over the figure for 2016, according to a recent study of 32 of the world’s largest economies. Technology driven productivity improvements will account for much of this expansion, which will significantly surpass population growth. The study projected that the economies of seven key emerging markets (the “E7”: China, India, Brazil, Mexico, Russia, Indonesia and Turkey) will on average grow twice as quickly as those of the G7 (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States). Consequently, six of the top seven economies in 2050 will be countries now classed as emerging, with the top 10 ranked thus: China, India, US, Indonesia, Brazil, Russia, Mexico, Japan, Germany and the UK. By the same year, the EU’s 27 member states (potentially without the UK after Brexit) are projected to account for under 10 percent of global GDP. (A separate analysis puts the EU’s share in 2019 – albeit including the UK – at 16%.) Also by 2050, several other emerging economies, such as Vietnam and Turkey, are set to rapidly overtake some more established European economies. The maturation of today’s emerging markets will reduce their appeal as low-cost manufacturing bases but make them “more attractive as consumer and business-to-business markets.”

Several other forecasts offer similar pictures of rapid global economic convergence, even if their timelines and rankings vary. The OECD predicts that living standards (measured by real GDP per capita) will continue to advance in all countries between now and 2060 and will gradually converge by varying degrees toward those of the most advanced countries.

If certain policy reforms (such as improving governance and educational attainment to the level of the 36 OECD states) take place in the emerging economies of Brazil, Russia, India, Indonesia, China and South Africa, their living standards could get an extra boost of up to 50 percent.

Snapshots of today’s migrant labour markets

Migrants and refugees account for around three percent of the world’s population, yet they contribute almost 10 percent of global GDP. They foster “native and aggregate prosperity, especially over longer time frames.” When they are highly skilled they “contribute substantially to technology innovation and research and development in destination countries – particularly high-income countries.” (That this cuts both ways to forge a sort of virtuous circle led one academic to offer a Swiftian solution to those determined to reduce migration: “wreck the economy”.)

The following snapshots illustrate the scale and diversity of existing migrant labour:

- In the UK, migrants from other European Union states numbered 3.7 million in the last quarter of 2018 and 83 percent of them who were of working age (2.3 million people) were employed. Food and drink production provides about a quarter of these jobs; other key sectors include: warehousing, accommodation and hospitality, construction, retail, residential and social care, professional services, and healthcare.

- Generally, across Europe, more than half of newly arriving citizens of non-EU countries are now admitted on rights based (family reunion) and humanitarian grounds (including refugee status) or arrive in mixed migratory flows and are later granted asylum. The primary reason for their acceptance is not related to any economic agenda or planning and the result is that their integration into formal labour markets is slow and limited, “reducing the potential economic gains from migration.”

- In the Gulf States, migrant workers make up most of the population – at least 80 percent in Qatar and the UAE. Most work in construction and as domestic staff, sectors in which migrant labour accounts for over 95 of the work force. Saudi Arabia absorbs millions of migrants, many of whom arrive in mixed flows through Yemen and work informally in agriculture, livestock, transport and construction. Saudi Arabia sporadically detains and expels large numbers of migrants; it did so in 2013, 2018, and 2019.

- In the agriculture, fishing, and forestry sectors in the United States immigrants make up 46 per cent of the workforce. Almost 20 percent of workers in the transportation sector, the country’s largest employer, are immigrants. In the top 25 sectors where migrants are most employed, there is much diversity between skilled and non- or semi-skilled workers. White-collar jobs in science, computing, engineering and architecture, healthcare, management, business, arts and media, and the legal professions have a high level of migrant participation by skilled, (and predominantly documented) migrants. In 2016, more than 11 million irregular migrants (many of whom had overstayed their visas) were living, and mostly working, in the US. Overall, migrants “play vital roles in the US economy, erecting American buildings, picking American apples and grapes, and taking care of American babies.”

- South Africa has a long history of migrant workers (permanent and temporary) who are well integrated into the labour markets. In some sectors, such as agriculture, forestry, fishing, mining, construction, wholesale and retail, and hospitality, up to a quarter of the workforce were foreign migrants in 2011. Overall, about four percent of working-age residents were born outside the country and this cohort has a higher rate of employment than native South Africans, although their jobs are more likely to be in precarious jobs or the informal sector.

- Malaysia’s economy relies heavily on migrant workers to perform low-skilled jobs. Approximately 30 per cent of workers in the agricultural, manufacturing, and construction sectors are migrants. There are an estimated 3–4 million migrants working in Malaysia of which about a half (1.7 million) were employed with legal documentation in 2017 while the rest were irregular. If irregular migrants are included, then approximately 30 per cent of Malaysia’s overall workforce are migrants.

Tomorrow’s labour markets

As sectors expand and contract over the course of economic cycles, both at a national level and in terms of their share of the global economy, a given country’s labour demand and its absorptive capacity of both regular and irregular migrant labour fluctuate. The International Labour Organization (ILO) predicts migration will intensify as “decent work deficits remain widespread” in countries of origin. Demographic dynamics will also have “profound implications” for national and global labour markets, while “machines are unlikely to fully replace the labour of human beings any time soon”. Meanwhile, the projected addition of 100 million elderly people and 100 million children under the age of 14 to the world’s population by 2030 is set to create millions of new job opportunities. Many of these jobs will need to be filled by migrant workers due to lack of available home-sourced workers, especially for long-term care.

More than half a billion new jobs will be needed by 2030 to accommodate the world’s growing labour force, even without taking into account potential increases in female and older-worker labour force participation, let alone migrants and refugees. This is particularly relevant to sub-Saharan Africa, where the working age population as a share of total population is “expected to continue to increase between 2015 and 2040, while it will stagnate in Latin America and decrease in East Asia as well as in advanced economies”. Even if developing economies achieve double-digit growth, analysts fear many of the growing number young people entering the labour market will be deprived of job opportunities.

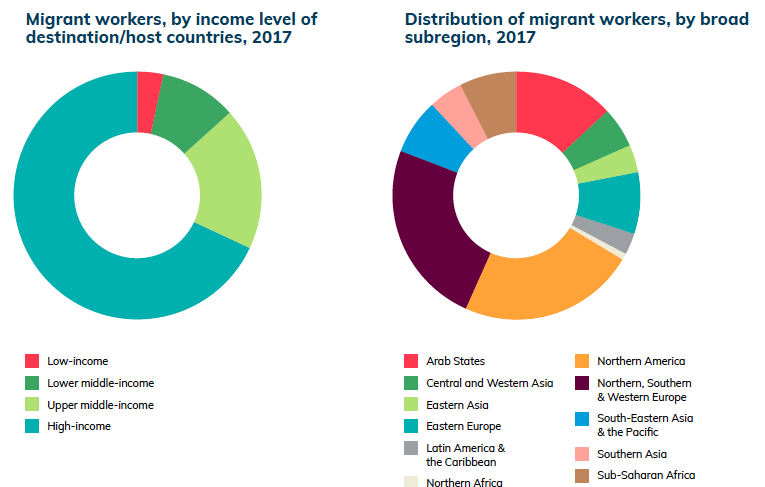

Source: International Labour Organization ILO Global Estimates on International Migrant Workers

Uncertain opportunities

Global economic growth does not guarantee greater employment opportunities for migrants because much of it is expected to derive from the increased productivity due to automation, and it is still unclear what impact this will have on replacing work or creating new work. The general expectation is that the initial waves of automation will have little effect on most of the low-skilled work currently undertaken by migrants, particularly irregular migrants.

The scale of unfilled work vacancies in some regions has been apparent for some time. In the European Union it is already significant, not only in highlyskilled occupations, but also “in medium-skilled and low-skilled occupations, including home-based personal care workers, cooks, waiters and cleaners”. As the expected G7/E7 convergence occurs, and as ageing and population decline bites in the global North, these labour opportunities can be expected to increase considerably. In fact, the question may be whether the emerging economies become a more potent magnet for labour migrants, resulting in developed economies struggling to attract the labour migrants they need.

Uneven markets

In some developing countries that are points of origin for mixed migration flows, economic growth most probably won’t deliver enough jobs to accommodate the rising number of citizens reaching working age. Afghanistan, for example, “is unlikely to make major progress in reducing poverty. Growth is expected to accelerate to around 3.7 percent by 2021. But with a current population growth rate of around 2.7 percent, a much faster growth rate will be required to significantly improve incomes and livelihoods for most Afghans, or provide jobs for the approximately 400,000 young Afghans entering the labour force every year.” The larger job markets and better security in some developing states – such as Kenya, South Africa, Nigeria and Ghana – already create a magnetic pull for the South-to South movement of millions of regular and irregular migrants, and many refugees. This trend is set to continue.

Climate change and other variables

These projected shifts in global economic characteristics will occur alongside, and be affected by, other megatrends that include rapid urbanisation, climate change and resource scarcity, demographic and social change, and technological innovations and disruption.

“Future forecasts vary from 25 million to 1 billion environmental migrants by 2050, moving either within their countries or across borders, on a permanent or temporary basis, with 200 million being the most widely cited estimate.” These kinds of movements would put significant pressure on urban centres to provide livelihoods to the displaced, or could result in significant cross-border irregular movement.

All this makes for a heady mix that impedes confident answers to pressing questions. Will climate-induced migrants be welcomed where labour demand exceeds supply, and unwelcome where wide-scale automation is shrinking job opportunities? Will they be a massive burden on cities (in the global South) where local unemployment is already high? What impact will wide-spread AI-led automation of the so-called 4th Industrial Revolution have on future societies and the labour market? What will labour markets look like once nascent sectors like biotech, robotics, autonomous vehicles and nanotechnology come to fruition? Will the effects of climate change turn out to be more, or less disruptive to global economies and societies than currently predicted?

Impact on migration

As the educational attainment and prosperity of those living in emerging and developing economies rise, the kind of work that will be increasingly shunned by native populations is likely to result in high demand for migrant labour. By the same token, emigration could become a more attractive option for new cohorts of better educated youths whose job aspirations go unmet or insufficiently remunerated at home.

Moreover, as emerging economies evolve from being dominated by manufacturing to more consumer- and business-to-business based economies, their demand for foreign labour is likely to rise. The demographic dividend could be a boon for developing countries while at the same time translating into an immigration dividend as both skilled and non-skilled workers find themselves in higher demand abroad.[1] In countries of origin, this will increase the share of gross national income that derives from remittances. Recorded annual remittance flows to low- and middle-income countries reached $529 billion in 2018, “an increase of 9.6 percent over the previous record high of $483 billion in 2017.”

Refugees’ right to work

Refugees’ right to work is enshrined in the 1951 Convention and other international instruments, and tracks with the Sustainable Development Goals to reduce poverty and inequality.

Respecting this fundamental human right is key to preserving human dignity and is also “beneficial to the societies in which they live and, where appropriate, the societies to which they return. The majority of these people [refugees and asylum seekers] are of working age and bring knowledge, skills and training with them. Allowing and enabling them to work reduces the likelihood of them taking up informal employment or becoming dependent on State support.”

Such benefits are obviously enhanced in aging societies whose native workforce is diminishing. Aside from granting refugees direct access to labour markets, investing in their language skills and educational qualifications promises high returns in terms of labour market integration and fiscal benefits.

Yet at the national policy level, international obligations and economic good sense are often trumped by popular opposition fanned by far-right groups, by “concerns of labor market distortion and limited capacity, decreasing jobs available to citizens, reductions in wages, and working conditions” as well as by an aversion to citizenship claims lodged by refugees who are allowed to work. Consequently, “efforts to implement work rights have been limited, and many of the world’s refugees, both recognized and unrecognized, are effectively barred from accessing safe and lawful employment for at least a generation.” A l ikely c onsequence of perpetuating such realpolitik is that mixed migration flows become the norm.

Female refugees often face higher hurdles to finding employment – let alone fair wages – than their male counterparts. Yet if female refugees were gainfully employed and paid the same as workers in the host population, they could add up to US$1.4 billion to global GDP.

Potential game-changers

In 2016, international donors and the governments of Jordan and Lebanon agreed on a pair of “compacts” in response to the exodus of Syrians since conflict broke out in Syria in 2011. Around 660,000 Syrian refugees now live in Jordan and almost a million in Lebanon. The compacts outline infrastructure projects, employment opportunities and basic services for refugees. Despite slow progress, the agreements have been described as “game-changing – not only for the Syrian crisis, but also as a model for refugee response around the world.”

Other examples of this new focus on “refugee economics” are being developed in countries such as Uganda and in Ethiopia’s special economic zones. Some of these ventures have been problematic and disappointing but represent a new approach to thinking about refugees even though some critics see them as effectively serving the western agenda of keeping refugees working in developing regions – far away from the global North.

Shadow worlds

Ineffective integration of migrants and refugees often stimulates secondary markets for informal labour that feed off irregular migration. The relationship between irregular migration and the informal economy is relevant to mixed migration flows because both undocumented migrants and failed asylum seekers – as well as victims of human trafficking – are often found in these un-taxed shadow economies, deprived of a wide range of rights and legal protections.

How do host states’ migration policies correlate with the real-world economic context where blind eyes are turned to cheap, agile, undeclared and unregulated workers? Increasing, regular migration may pay economic dividends but, for reasons outlined above, is often politically unpalatable. This is a reality that the United States, with its continually high level of deportations and newly-accelerated processes, has accepted for decades – and Europe too, albeit more recently and to a lesser extent. Such conflicting imperatives are particularly evident in Saudi Arabia, which sporadically expels millions of irregular, mostly low-skilled workers in the name of “Saudisation”, despite a persistent demand for labour deemed too menial by most Saudi citizens. The informal sector tends to find ways to bridge the gaps.

Conclusion

Stepping back, the current approach is as irrational as it is inefficient. The political energy and financial costs associated with keeping migrants and refugees out of countries (and their labour markets) is astronomical and increasing rapidly every year. The world’s border security sector is estimated to have been worth 15 billion euros in 2015, a figure that is projected to almost double by 2022. Meanwhile, irregular migrants and refugees collectively spend hundreds of millions of dollars annually on smugglers, bribes and ransom payments, transport and fake documentation, etc. At the same time, destination countries spend billions subsidising or otherwise protecting strategic sectors such as agriculture, making it difficult for businesses in origin countries to compete, resulting in fewer jobs and more migration, much of it entailing deadly perils en route.

In a more sustainable and efficient scenario, migration and asylum applications would be preferred to the prevalent irregular mixed migration, which creates so much misery for those using these channels, and so much political anxiety for destination countries. This is the vision of the 2018 Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration. Its aims include promoting increased regular migration channels, greater investment in training and empowering migrants and societies to realise full inclusion and social cohesion. Objective 16 urges nations to “work towards inclusive labour markets and full participation of migrant workers in the formal economy by facilitating access to decent work and employment for which they are most qualified, in accordance with local and national labour market demands and skills supply”.

It remains to be seen how far this non-binding agreement will stimulate effective policy reform on the ground. But it is clear that as demand – and indeed competition – for migrant labour increases with economic growth, governments and societies need to find smarter and safer migration pathways.

[1] The UN Population Fund defines the demographic dividend as “the economic growth potential that can result from shifts in a population’s age structure, mainly when the share of the working-age population is larger than the non-working-age share of the population.” See also the essay, The ‘immigration dividend’ in a world of demographic turbulence in this report