After the chaotic scenes of the last two years in Europe the call for well-governed migration is louder than ever. Not just scenes from Europe – of refugees and mass flows of migrants and refugees breaking through border fences, clashes with police, tear gas, families sleeping in the open for weeks and bodies being lifted from the sea – but also from Australia, North America and South Asia. Scenes too of detention, deportation and death, have become all too common.

As the sheer numbers of migrants, refugees and displaced people increase to highest recorded levels, the need for better migration management is becoming more acute. But what is well-governed migration? What would it consist of and how would it be measured? This feature discusses a new proposition of a Migration Governance Index (MGI) and describes its features and intentions.

Designed by The Economist Intelligent Unit, commissioned and assisted by the International Organization for Migration (IOM), in its inaugural publication in April 2016, the MGI presents a new methodology for measuring migration governance and tests it on 15 countries worldwide as part of Phase One. A second phase will be to replicate the same exercise in a larger number of countries.

The 15 pilot countries, (see the graphic for those included below) were, according to IOM, selected on the basis of regional balance, broad migration trends, and economic performance although they appear to include few low income countries including any from the East and Horn of Africa. The index includes both qualitative and quantitative indicators with what is referred to as ‘rigorous weighting and scoring system’ aimed at ensuring validity of the index and consistency across countries.

Cautious of controversy, the designers are emphatic that the index should not establish a global ranking of states on migration policy. Additionally, they argue that a global comparison would also have limited meaning as countries face different challenges and opportunities in relation to migration, and have largely different resources to allocate to migration management. Instead of ranking, the index aims to act as a ‘benchmarking framework’ that offers insights on ‘policy levers’ that countries can action to strengthen migration governance.

As an important part of its rationale, the new index aims to respond to the need for a measurement tool following the inclusion of explicit migration objectives listed in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) adopted by the UN General Assembly in September 2015. Although migration relates to various goals and targets in the SDGs, Target 10.7 features migration directly tasking nations to ‘facilitate orderly, safe, regular and responsible migration and mobility of people, including through the implementation of planned and well managed migration policies’. So what are well-managed migration policies?

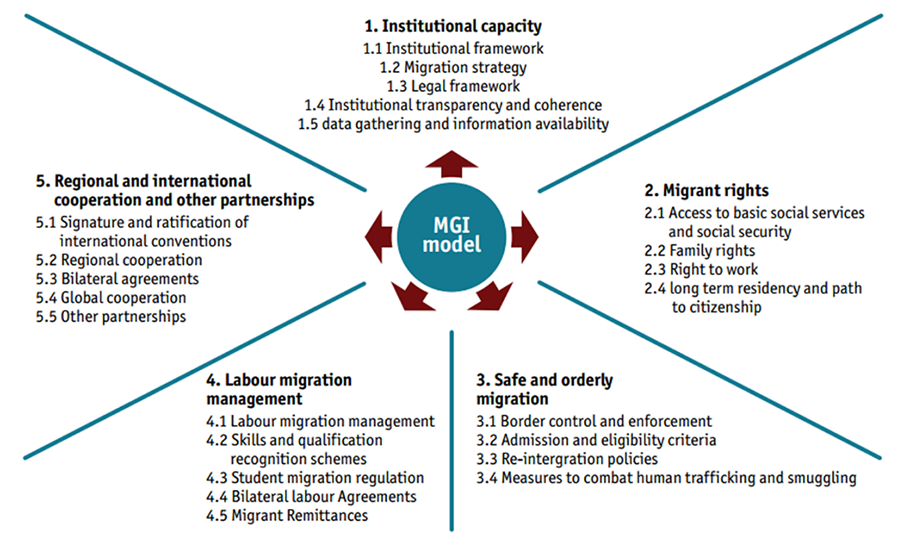

The Migration Governance Index uses 73 qualitative questions to measure performance across five domains identified as the ‘building blocks’ of effective migration management. The domains are, 1) institutional capacity, 2) migrant rights, 3) safe and orderly migration, 4) labour migration management, and 5) regional and international cooperation and other partnerships. Each domain has sub categories and the full range of areas covered are shown below:

Source: The Economist / IOM 2016 MGI report

Deficiencies around safety measurements

While not attempting to offer a comprehensive critique of this model, RMMS notes that when measuring ‘safe and orderly migration’ the sub categories (3.1 to 3.4) only refer to aspects reflecting ‘orderly’ migration and omit to mention any relating to ‘safe’ migration. Some critics have cited the inherent problem of combining safe and orderly into one target by the drafters of the SDGs themselves.

Specific safety criteria are relevant because of the rise of irregular migration due to of the lack of availability of legal migration channels, which will continue to result in the movement of people via irregular and increasingly unsafe channels. Additionally, the MGI domain 2 – Migrants Rights focuses on migrants who are in-country already, overlooking the fact that there is a human rights obligation to also safeguard the rights of those who are on the move transiting sovereign territory – a most unavoidable reality that is part of the irregular phenomenon and of course, where most violations occur.

The notes for target 10.7 in the SDGs includes “Effective governance under the rule of law is also required to prevent abuse and exploitation of migrants, contain xenophobic hostility, and sustain social cohesion”. It could be argued that such an explicit reference should have led to an indicator on safety alone. Equally, the MGI assessment model does not focus on these aspects.

Deficiencies around return measurement

Another observation concerns the implementation of policies and laws related to the return (forced or voluntary) of migrants in irregular flows and asylum seekers whose applications have been refused. Adhering to such rules (such as the Return Directive of the EU) could be seen as a critical aspect of an effective migration policy – maintaining the credibility of the refugee regime while signaling to smugglers and those in irregular flows that countries are serious about refusing those without access entitlement. While indicators used to inform the MGI cover issues of return from the re-integration side, measurement of adherence and implementation of return appears to have been left out entirely by the MGI domains and the many indicators that inform it.

Avoidance of ranking

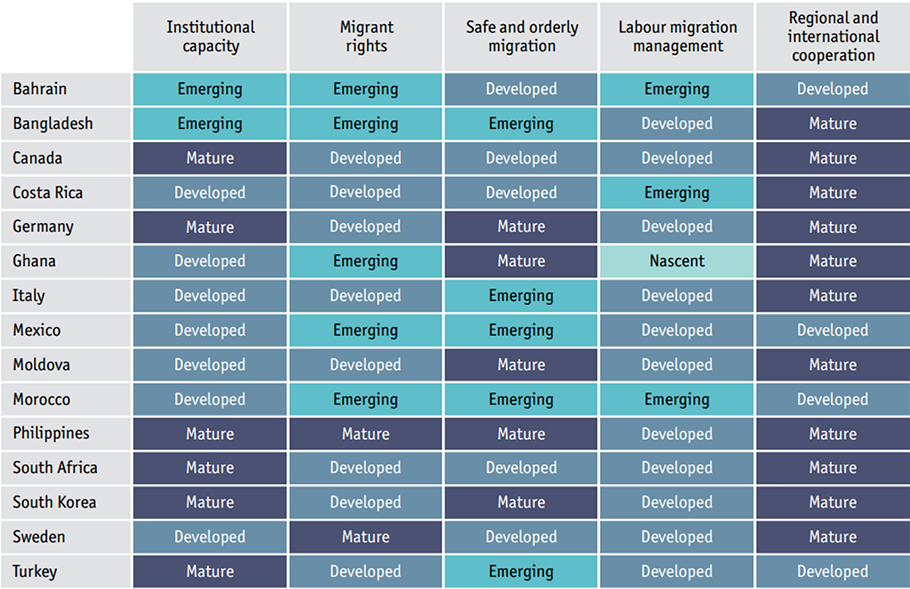

The wisdom of not accumulating findings to create an absolute ranking is that this system allows the observer to see where each country has successes and failing without offering a single absolute score. After all, the domains are sufficiently diverse that combining scores would offer little idea of the actual state of migration governance in a particular country. For example, from the findings (tabled below), Ghana, scored well (Mature) on regional and international cooperation (the same as Germany), but scored poorly (Nascent) on labour migration management (where Germany scored Developed).

Bandings are based on a scale of 0-10 where 10 is best. Nascent: 0-2.49; Emerging: 2.5-4.99; Developed: 5-7.49; Mature: 7.5-10. (source of graphic: The Economist / IOM 2016 MGI report)

Despite these caveats the table illustrating the findings for Phase One show some surprising results. The Philippines scores best, better than Canada and Italy, while South Korea did better than Sweden.

This is not the only attempt to measure aspects of migration management. Amongst others, the Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has on-going measuring projects (IMPIC and IMPALA), while the European Research Council-funded DEMIG project also seeks to capture and measure policy used by various countries. The difference is that the new MGI will attempt to offer an index for a far wider number of countries in all global regions and also intends to run indefinitely offering multi-year measurements that can chart improvement and progress.

Who decides what is ‘good’?

The MGI’s designers claim that its broad focus gives policy makers a 360-degree overview of important areas where national policies can be improved. However, any attempts to measure results will be forced to lean on preconceived notions of praise-worthy practice, with a tacit or implicit notion of what ‘good’ governance should be. One country’s, or political party’s, meat may be another’s poison – one country’s preferred and responsible policy may include government action that another country would regard as oppressive and a violation of migrants rights. In a context where migration policy is increasingly politicised and polemical, the MGI is bound to be contentious although the MGI debut contribution to the sector deserves to be widely welcomed.

Note: This article originally appeared on the RMMS Horn of Africa website.