When considering the future, the nexus between the environment and mixed migration demands attention for two primary reasons. First, climate change and environmental stressors affecting human populations and mobility are unquestionably already well underway and set to intensify.

Second, the designation, legal status, and rights of those displaced by environmental factors are so unclear and contested that this lack of status and poverty of options will force many into mixed migratory irregularity and increased vulnerability, while potentially creating significant humanitarian crises for those displaced, without affording access to international protection.

The story so far

Climatic events and changes can affect human mobility either directly or, more commonly, in combination with other factors. Changes may be acute or gradual and may result in temporary or permanent migration, normally within affected countries, but also internationally.

Growing vulnerability

In many parts of the world, migration, displacement, and organised relocation are increasingly affected by environmental processes including climatic variability (storms, drought, and other kinds of weather shocks such as heatwaves, floods, and cyclones), and shifts in climate patterns associated with glacial melt, sea-level rise and desertification. Communities living in low-lying islands and deltas, coastal zones, glacial-fed water systems, and regions subject to persistent drought are particularly vulnerable.

Almost 30 years ago, in 1990, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) noted that the greatest single impact of climate change might be on human migration, with millions of people displaced by shoreline erosion, coastal flooding and agricultural disruption. A background paper for the UN’s 2007 Human Development Report pointed to a growing body of opinion that “environmental degradation, and in particular climate change, is poised to become a major driver of population displacement.” Of course, it was already such a driver at the time, and now, in 2019, evidence of climate-induced mobility, be it forced or voluntarily, can be found in regions and communities all over the world. The critical finding of various recent studies is that global environmental change affects the main drivers of migration. This will be discussed in more detail below.

Major driver

In one recent study, where 16 destination and 198 origin countries were analysed for migration correlations over a 34-year period (1980-2014), academics from New Zealand found that climate change was a more important mobility driver than income and political freedom combined. They also found that a long timeframe is key to understanding the effects of climate change, and described their findings as “just the tip of the iceberg” given that climate-induced movement (internal and external) is often not documented or recognised as such. Other studies report less conclusive evidence about the effect of climate on international migration. But there is a broad consensus that environmental factors are and will continue to be a major contributing factor in internal migration and internal displacement. This usual takes the form of rural-to-urban movement, but can also take place from one rural area to another, particularly in developing

countries. The World Bank’s recent Groundswell report focuses on internal displacement in detail and is an important reference in this essay.

Disasters displace millions

Disasters triggered by natural hazards are the leading cause of environment-induced internal and international displacement. The impact of climate and sudden environmental stressors and shocks is clear: the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) estimates that 17.2 million people were displaced by such hazards and extreme weather in 2018 – that’s more than 47,000 per day or almost 2,000 every hour of that year. In 2015, IDMC calculated that in each of the preceding six years, an average of 26.4 million people were displaced from their homes by disasters brought on by natural hazards.

Based on current measurable trends, primarily in the most impoverished countries, there are five patterns of displacement: temporary; permanent local; permanent internal; permanent regional and permanent inter-continental. The last two patterns are relevant to mixed migration flows, although the other forms of internal displacement (which accounts for most environment-induced displacement) can lead to subsequent regional and inter-continental movement.

Looking ahead: the next few decades

Although the relationship between climate and migration has been well established, it is unpredictable: “the science of climate change is complex enough – let alone its impact on societies of differing resources and varied capacity to adapt to external shocks.” Nevertheless, the inertia in the climate system means that climate change over the next few decades at least is fairly predictable, notwithstanding issues around tipping points, discussed below. “The extent and nature of climate change after 2050 is therefore predicated on current emissions. Consequently, many analysts think that it is highly speculative to try to push predictions past 2050.”

In 2011, the UK government’s Foresight project predicted in a major report that the impact of environmental change on migration, specifically through its influence on a range of persistent economic, social, and political drivers, would in increase, and said this had “potentially grave implications […] for individuals and policy makers alike.”

Estimates of the numbers who will migrate within or across borders because of climate change by 2050 range from 25 million to one billion. This is explored in greater detail below.

Involuntary immobility

An important finding, echoed by the more recent World Bank report, is while that environmental change is likely to make migration more probable, it could also make it less possible. Migrating can be expensive, and people lacking capital, in the form of financial, social, political or physical assets, as a direct or indirect consequence of climate change, may be unable to move away from locations where they are extremely vulnerable to environmental change. A more likely response to slow-onset environmental stress is not to immediately migrate far away, but to first try other coping mechanisms, such as moving to a nearby location (perhaps an urban area), or taking on an extra job or a loan. Once other options have run out, people may wish to migrate but find they then lack the resources to do so. In other cases, involuntary immobility may occur in the event of sudden hazards, such as major floods affecting large populations, as happened in Mozambique this year and in New Orleans in 2005 after Hurricane Katrina.

The Foresight report warned of millions being potentially “trapped” and facing “double jeopardy: they will be unable to move away from danger because of a lack of assets, and it is this very feature which will make them even more vulnerable to environmental change.” To the international community, such people represent “just as important a policy concern as those who do migrate,” not least due to the humanitarian crises this may cause.

The report’s authors conclude that preventing or constraining migration carries risks: “Doing so will lead to increased impoverishment, displacement and irregular migration in many settings, particularly in low elevation coastal zones, drylands and mountain regions.”

Climate change as a threat multiplier

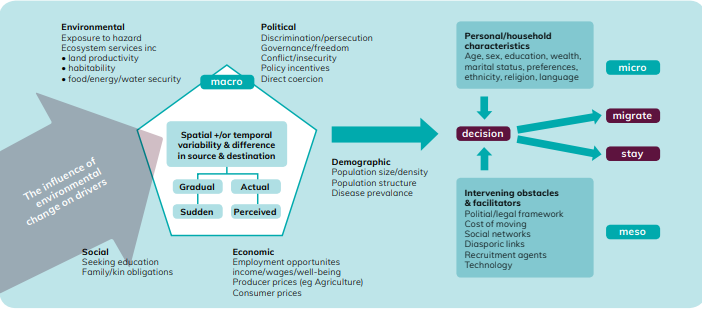

In recent years, analysis has increasingly framed climate change as a threat or stress multiplier that exacerbates complex and location-specific conditions, sometimes to a tipping point that leads to migration. This is because climate change has an impact on the political, demographic, economic, social, and environmental factors that can drive migration. Drivers are interconnected, their categories “permeable” and climate change may have a greater impact on some drivers than others: one “may cause the other or, more likely, each drives the other in a vicious cycle of reinforcing degradations”.

The diagram below, adapted from the Foresight report, illustrates how “global environmental change affects the drivers of migration.”

A catalyst for conflict

With respect to forced displacement, flight, and irregular movement, the issue of conflict and its relationship to climate change is sobering. The potential impact of climate change on natural resources, livelihoods, impoverishment, and inequality contributing to mass mobility “is why military minds around the world take climate change very seriously indeed as a threat multiplier with direct consequences for peace and security.” Climate change can exacerbate a wide range of existing, interrelated, non-climate threats, including security, and serve as a catalyst for conflict. The world’s development and sustainability trajectory is expected to significantly influence how climate will actually influence conflict drivers and risks. There is no separating of the issues. These cascading impacts linked to climate change are already shifting patterns of migration and “will increasingly do so.”

Looking forward, the growing impact of climate change – as a future catalyst – is therefore set to “threaten livelihoods, increase competition, intensify cleavages, reduce state capability and legitimacy, trigger poorly designed climate action with unintended consequences, and lead to large movements of people…” Groundswell’s analysis of cross-case quantitative studies finds significant statistical correlations between climate change and violence or conflict in scenarios where needy people move into areas where competition for scarce resources may already be strained. “If human responses to climate change remain unchanged, climate change has the potential to increase violence and conflict causing migration and flight.”

Resistance to mixed flows

Even if the primary impact of future environmental stress is high levels of internal displacement, the numbers in irregular mixed migration flows of people seeking alternative homes, livelihoods and refuge would inevitably grow, as the global appetite to absorb refugees and irregular migrants in their millions will be meagre at best. If numbers in such flows are large and are perceived as threatening, future mixed migration flows may face harsh responses and determined resistance. This is already happening, despite international agreements such as the global compacts on migration and refugees promoting a less restrictive approach.

Migration drivers and environmental change

Source: Foresight (2011) Migration and Global Environmental Change Final Project Report

Migration as adaptation

Human movement is widely recognised as an adaption strategy in response to the direct or indirect impact of climate change. The IPCC defines adaptation as the process in human systems “of adjustment to actual or expected climate [change] and its effects, which seeks to moderate harm or exploit beneficial opportunities.” Migration is a common coping, income diversification, risk management, and adaptation strategy for people facing economic stress and adverse climatic conditions. It is also a strategy of last resort. As such, climate migration is a critical response that is neither inherently good nor bad, despite some prevalent negative narratives and efforts to prevent internal or international movement: “The cost-benefit calculus is heavily dependent on perspective.” It is generally accepted that climate change will hit poorer countries and communities disproportionately, and vulnerable people often have the least opportunity to move, or do so only under distress conditions.

Better than staying put

Migration may increase adaptive capacities, defined as the “abilities of people and societies to transform structure, function, or organisation to manage better their response to weather hazards and other negative changes.” Migration at the household level may not be the first or only adaptive strategy chosen or, indeed, the most appropriate, but the evidence for many decades has shown that in fragile environments “migration is essential in preserving life and satisfying basic needs.“

Studies from various countries indicate that those who migrate internally with more assets and capabilities tend to do better than those do not migrate, and the outcomes of both those who migrate with assets and those migrate without are better than those who did not migrate from the same conditions of stress.

The bulk of climate-induced migration over future decades is expected to be internal. Internal migration and rural-to-urban movement on a mass scale in recent decades has been shown to be a clear adaptation strategy, with Groundswell citing at least three times more people having migrated within countries than across borders in 2013, and about twice as many people displaced internally than across borders in 2016.

Time to plan

The report adds that by 2050, two-thirds of the global population is expected to be living in urban areas. Even without climate change impacts, rising internal migration from population increases and urbanisation “means that effective management strategies [in terms of urban planning and management policies] are indispensable.”

What happens in the second half of the 21st century depends to a great extent on what we do today and have done in the last decade. It is worth noting that most recent IPCC reports indicate that the situation is deteriorating faster than expected.

Impossible to count

Consensus continues to elude estimates of the number people expected to be displaced by environmental changes: these range from 150 million to 300 million by the middle of this century. The figure that has gained the most traction in the media and key publications such IPCC reports and the landmark Stern Review is Oxford University’s Professor Norman Myers’ 2005 prediction that there will be 200 million “environmental refugees” by 2050. By that year, warned Myers, 162 million people in Bangladesh, Egypt, China, India and other parts of the world, including small island states, will be vulnerable to sea-level rise and another 50 million to desertification.

More recently, Myers has suggested that the figure by 2050 might be as high as 250 million.39 These figures surpass many times over those of conventional refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs – currently numbering over 70 million, according to UNHCR) both now and those expected in the future. Meanwhile, the Groundswell report estimates with painstaking methodological detail that there will be more than 143 million internal climate-induced migrants in Asia, Latin America and Africa by 2050.

Estimates challenged

Some researchers and analysts regard Myers’ figures as unfeasibly high and produced as grist for “maximalist” side of the debate. Critics point out that past predictions of vast numbers of environmental migrants have not come true and that the larger estimates are usually based on the number of people living in regions at risk, rather than of those expected to actually migrate. Such estimates do not account for adaptation strategies and alternatives to migration, or the issue of trapped, or involuntarily mobile, populations.

Foresight, for its part, found that such estimates are somewhat dubious as it is almost impossible to distinguish environmental migrants from others on the move “either now or in the future, as migration is a multi-causal phenomenon and it is problematic to assign a proportion of the actual or predicted number of migrants as moving as a direct result of environmental change.”

Considering the UN’s (also contested) estimate that the global population will reach 9.7 billion by 2050, Myers’ higher estimate of 250 million climate-induced migrants and Groundswell’s estimate of 143 million internal migrants represent approximately 2.5 percent and 1.5 of the global population respectively. Given the severity of the predicted impacts of climate change globally it could be argued that these are relatively modest numbers to be managed. On the other hand, refugees as defined by the 1951 Convention, who now make up under 0.3 per cent of the current (undisputed) global population, already seem to present a seemingly intractable challenge at the political and societal level, with most living in dire, protracted situations with no durable solutions in sight.

Lost in law: The definition dilemma

What one analyst wrote in 2007 is equally true today: “so far there is no ‘home’ for forced climate migrants in the international community, both literally and figuratively.”

Terminology trouble

Different terms are applied to those moving for environmental reasons, including environmental or climate refugee and environmental or climate migrant.[1] From a legal perspective the term “environmental refugee” is a misnomer and today most literature avoids the expression.

In international law, the status of people leaving their place of residency for environmental reasons remains undefined, mainly due to the aforementioned difficulty of isolating environmental factors from other, often related, drivers of migration and because such people are not covered by the 1951 Refugee Convention. Forced climate migrants therefore fall through the cracks of international refugee and immigration policy, presenting a potentially huge dilemma for agencies and governments while “protection for the people affected remains inadequate.”

According to the Environmental Justice Foundation, a UK-based nonprofit, “climate refugees” outnumber refugees fleeing persecution and violence by more than three to one. A recent European Parliament briefing paper cites the examples of “the estimated 200,000 Bangladeshis, who become homeless each year due to river-bank erosion, and cannot appeal for resettlement in another country, [and of] the residents of the small islands of Kiribati, Nauru and Tuvalu, where one in ten persons has migrated within the past decade, [but] cannot be classified as refugees, even though those who remain are ‘trapped’ in worsening environmental conditions.”

The need for recognition and protection

Some experts have called for formal recognition of climate-induced displacement, noting that the distinction between forced and voluntary movements of people is a cornerstone of legal regimes at international and domestic levels, and arguing that, when return is not permissible, feasible or cannot be reasonably expected, protection and assistance must be offered. The same experts recommend that climate IDPs should be treated according to the 1998 UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement and relevant domestic and regional law. In the case of international migrants, they should be admitted and granted at least temporary stay in the country where they have found refuge until the conditions for their return in safety and dignity are fulfilled.

New instruments

This legal void in which climate-displaced people find themselves gave rise to calls for a new, binding international instrument. The Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration, adopted in late 2018, was the first international agreement to specifically recognise migration’s links with climate change and natural hazards. It advocates various international cooperative responses or solidarity, but still avoids offering those displaced by the environment any special protection through legal status. Meanwhile, the Global Compact on Refugees stopped even shorter, only mentioning climate as one of many factors that “may interact with the drivers of refugee movements.” Both compacts are voluntary.

The Platform on Disaster Displacement, launched in 2016 (previously the Nansen Initiative) by a coalition of national governments, tries to fill the void. It encourages countries to assist climate induced migrants despite the lack of legal recognition of their plight. It builds on a Protection Agenda that 109 countries endorsed in 2015, and aims to integrate its principles into national laws.

But because of the potentially huge numbers involved, most governments are fearful of setting precedents by granting asylum on account of climate change. In 2017, New Zealand contemplated offering experimental humanitarian visas to people displaced from Pacific Islands by climate change after a tribunal denied refugee status to two such families from Tuvalu, but the idea did

not translate into action.

Kenya arguable offers a precedent of people escaping weather shocks in one country attaining refugee status in another, but it is somewhat tenuous: in 1992 hundreds of thousands of people fled civil war and famine in Somalia for Kenya. The numbers were too large for each to be assessed individually, so Kenya grudgingly granted them group prima facie refugee status, a category that restricted their movement and rights, but which endured, amid intermittent drought and conflict in Somalia, until 2016.

Why definitions will be critical

From a legal perspective, how will the world respond to potentially tens of millions of climate-induced migrants and asylum seekers when they have no official status? Those that can cross borders and seek work and new lives in a regular manner may only be a small, or minute, proportion of the total number. Others, if they have the means to do so, will move irregularly, probably with brokers and facilitators – human smugglers – and the risks of human trafficking are likely to rise. Those feeling compelled to leave their home as forced climate-induced migrants may seek to apply for asylum in countries that do not recognise their predicament as deserving refugee status. Most will be rejected and may be detained and deported or halted in their journeys before they arrive at their preferred destination country or region’s border. This in turn could lead to increased application of the restrictive policies currently implemented in Africa and Mexico under the instigation and insistence of the EU and the United States through local governments.

The question of return is critical here and a major dilemma for countries that do not accept environment-induced displaced people as refugees but which at the same time cannot return people to places suffering drought, famine, food security crises compounded by conflict or human insecurity.

Internal climate-induced migrants may be assisted as IDPs but will most probably continue joining urban populations and swelling cities’ ranks of urban poor in line with current trends. But those who cross borders, leaving rural areas or overcrowded, climate-vulnerable cities of the future will de facto join mixed migration flows, entering and transiting countries irregularly, often facing right abuses and security risks as they travel.

Recognition and responsibility

Without official status and given the numbers predicted to be displaced by climate change, it’s difficult to see how climate-induced migrants will not, quite rapidly, become a major social, political and humanitarian issue in some regions. How will the world deal with and categorise them? Will they be shunned and marginalised, will they be criminalised, arrested and deported or imprisoned? Agreement on their legal categorisation is urgently needed, but as long as recognition confers responsibility, the process is fraught with dilemmas for authorities reluctant to take on such responsibility.

The Nansen Initiative and the Platform on Disaster Displacement have warned of this dilemma with efforts to alert policy-makers of the legal gaps and risks. For the Executive Director of the Environmental Justice Foundation, “the situation and scope of this problem is entirely new, and of biblical proportions. It demands an entirely new legal convention. The global compacts are a

start, but it’s clear that they’re not enough.”

A future world of uncertainties

Predicting future outcomes on most subjects is a precarious exercise in a rapidly changing world. Not least with the environment, where the issue of tipping points is so relevant. Tipping points exist because of nonlinearity – the fact that there is no simple proportional relationship between cause and effect concerning climate change. “A tipping point is a particular moment at which a component of the earth’s system enters into a qualitatively different mode of operation, as a result of a small perturbation. Abrupt climate change occurs when the system crosses this tipping point, triggering a transition to a new state at a faster rate.”

No choice but mixed migration?

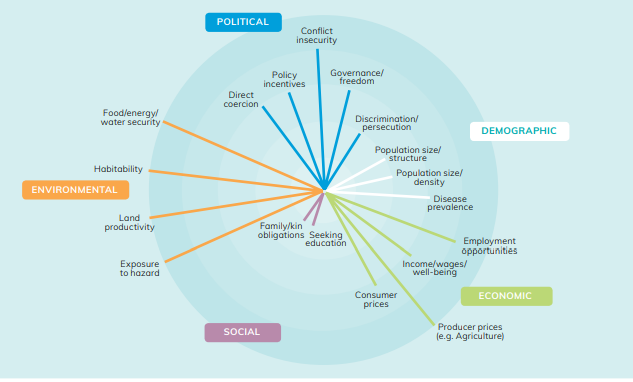

For those who wish to travel out of their region, either willingly or compelled by necessity, will the world be a more open and welcoming place than it is today? If solutions cannot be found for 98 percent of today’s Convention refugees, what choice will far larger numbers of status-less people have but resort to travel in mixed and irregular migration flows or remain stranded? The numbers of people attempting to move in mixed migratory flows, crossing borders and transiting countries irregularly, will very likely be high. Other key drivers, such as demographics, politics and socioeconomics, are expected to intensify in coming decades, and act as stressors on mobility in their own right. As a result, distinctions between political and climate-induced asylum seekers, economic migrants, and others on the move will potentially be more blurred as different stressors interact, reinforcing and exacerbating conditions and making it harder to isolate individual drivers. The diagram illustrates the links between migration drivers and environmental change.

The relative influences of environmental change on the drivers of migration

Length of line represents influence of environmental change on the driver; the longer the line, the greater the influence. Source: Foresight (2011) Migration and Global Environmental Change Final Project Report

Without channels for regular migration or prospects of being accepted as refugees with status and entitled to international protection, millions of people may be stranded and helpless, leading to frequent destitution and humanitarian crises. Ironically, in the more globalised and technologically connected world of the future, the conditions are likely – without a dramatic change in policy and attitudes – to be more inhospitable for those crossing borders uninvited, unmanaged or undocumented.

The number of people who will be forced into mixed migration in the coming decades is unknown, of course, but given the expected impact of climate change and other related drivers it is unlikely to be insignificant. Climate-induced migration and displacement is falling into policy gaps. “Existing international frameworks and national policies are yet to make the crucial link between climate change impact on the frequency and intensity of extreme climate events, environmental degradation and human mobility.” Political obstacles are significant. Governments prefer bilateral solutions to cross-border migration and displacement, and tend to discourage internal rural-to-urban migration. Governments also often fail to understand that people will migrate, even if a safe, legal option doesn’t exist. “Governments have a stark choice ahead of them. They can either facilitate safe, legal migration. Or they can attempt to stop people moving and create crises.”

[1] Related terms include: ecological refugee, forced environmental migrant, environmentally motivated migrant, climate change refugee, environmentally displaced person, disaster refugee, environmental displacee, eco-refugee, ecologically displaced person, or environmental-refugee-to-be. See: Boano, C., Zetter, R., & Morris, T. (2008) Environmentally Displaced People: Understanding the linkages between environmental change, livelihoods and forced migration Refugees Studies Centre