The following essay was originally compiled for the Mixed Migration Review 2019 and has been reproduced here for wider access through this website’s readership.

The politics around migration, especially irregular migration, has been highly dynamic in recent years in many parts of the world. Irregular mixed movements have had a major impact on domestic and international politics in the United States, Europe, Australia, Central and South America, Africa and Asia. In this new “age of migration”, the saliency of migration has been giving rise to ever more robust “migration diplomacy” in the international sphere, while providing potent fuel to populist and nationalist politics.[1]

Current iterations of anti-migrant and anti-refugee politics are potent and are making significant strides in normalising politics and policies that until recently were considered extreme. But the future trajectory is uncertain, as global politics around mixed movement will be shaped by economic necessity and the continued impact of globalisation and multinationalism, potential generational differences in attitudes to multiculturalism, and the fuller impact of climate change. This essay will offer an overview of current trends relating to the politics of mobility and identify pressures and processes that may indicate where the future of migration politics is headed.

Nationalism comes out of the closet

Much has been written and spoken about the rise of nationalism and nativism in global politics. When powerful nations such as the US, China, Russia, India, Brazil, Australia, Turkey and Japan have leaders and governments with explicit nationalist agendas, people pay attention. Many member states of the EU and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) are led by political parties with nationalist anti-migrant agendas (see table opposite), or at least such parties feature prominently in their political landscapes. Even if it can be argued that “there is no universal trend towards nationalism”, nationalism has undoubtedly become more prevalent in global politics in recent years.[2] According to some, “this increased visibility is less attributable to a shift of global attitudes, but rather reflective of the political and social articulation of these attitudes.”[3] In other words, attitudes to migrants and refugees now occupy a critical space in political and social discourse.

The roots of anxieties about and reactions to migration and refugees may lie in economic and societal changes. In some countries they are “grounded in the resonance of anti-elite discourse and a crisis of liberal democracy”, but they find ready expression through identity politics and populist nationalism.[4] These political trends often include forms of xenophobia and nativism.

Pervasive myths

“Misconceptions around migration abound.”[5] Migration is widely believed to be both more extensive and less economically valuable than the evidence shows it to be in reality. “Changes in attitudes towards migration are disconnected from economics” in so far that people fail to see the considerable benefits migrants and refugees can contribute economically.[6] Such misconceptions buttress a negative narrative rather than a positive one, and so “continued rapid immigration may foster additional support for far-right parties…”[7] There are no clear relationships between changes in public attitudes towards migrants and the extent of countries’ economic interest or imperative in accepting them.

The power of migration and refugee discourse to influence, shape, and lead national political agendas has been on the ascendant, irrespective of the facts and realities. The issues have acquired a force and momentum far greater than they deserve but in so far that “nationalism today works to protect against real or perceived predation,” the political framing of mobility has become polemicised, if not radicalised.[8]

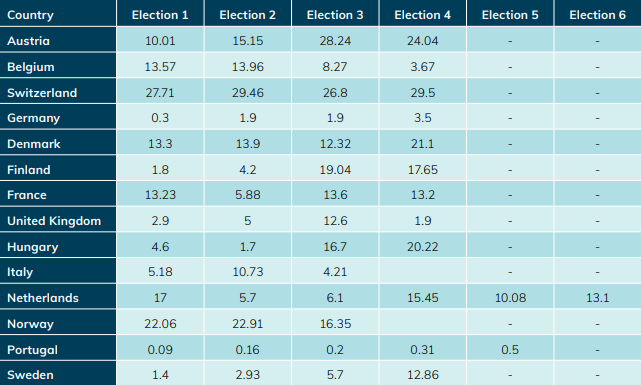

Prominent anti-immigrant and far-right parties in selected European countries

The disruptive impact of mixed migration

The much-publicised phenomenon of mixed migration, exemplified by media coverage of large groups of foreigners irregularly crossing seas and land borders, or being restrained by border police, has greatly disrupted political space.[9]

The disruption is disproportionate. Generally, far fewer people enter any given country using irregular channels than fall into irregularity there through visa overstays, visa fraud and other immigration infractions, let alone the millions moving through regular means. (The US/Mexico border is something of an outlier: hundreds of thousands of irregular, undocumented migrants and asylum seekers have crossed it annually for decades). The impact of the images of and anxieties arising from the 2015 and 2016 “crisis” in Europe, for example, lives on, and is often sensationalised by the media and weaponised for political ends by far-right and populist political parties which directly feed off migration fears.

Capitalising on chaos

Even in mid-2019, when numbers crossing the Mediterranean were the lowest for five years – 90 percent lower than in 2015 – images and stories of migrant drownings, or of desperate migrants trying to swim to Lampedusa from a rescue ship stuck in limbo by international politics and squabbling, create an exaggerated sense of chaos and absence of control. This is, of course, exactly the narrative that some political groups thrive and capitalise on, as it allows them to distort the debate about migration and refugees from the rational to the irrational.

The same can be seen in the US, where migrant caravans in 2017 and 2018 were taken up by President Donald Trump and other Republican Party politicians as a cause célèbre. They invoked narratives of “invasion”, “infiltration” and even terrorism, and churned out the tired canards of foreigners stealing jobs, sponging off welfare, and committing crimes.[10] Apart from the Republicans seeking to profit from the tough border approach in mid-term congressional elections in 2018, the narrative justified sending soldiers to the border, putting pressure on Mexico to restrict movement through its country, limiting asylum options, and increasing detentions and deportations – all measures designed to appeal to anti-migrant voters and boost the President’s support through vociferous politicisation of migration and asylum issues.

The centre shifts to the right

This disruption and distortion can be felt throughout the body politic. In Europe and Australia for example, right-wing parties have been so effective in exploiting the migration and refugee issue to beef up electoral support that mainstream parties adopted more restrictive and anti-migrant policies in order to compete. Centrist and even left-wing parties feel they cannot afford to appear “soft” on migration or asylum for fear of being punished at the ballot box, as happened in Sweden’s September 2018 elections where the anti-migration Sweden Democrats continued its rise by winning 18 percent of the vote.11 “Faced with a pro-migration political establishment, the silent majority of voters began to feel they had no other outlet than fringe parties with racist roots.”[12]

A recent instance of the salience of anti-migration attitudes taking hold in traditionally non-right-wing parties was the June 2019 general election win in Denmark by Social Democrat Mette Frederikson. She took over from a right-wing coalition government that had enacted the “most anti-immigration legislation in Danish history” and, rather than revoking it, she “has embraced much of it.”[13] Frederikson was reported to have campaigned with an “unapologetically hard-line anti-immigration stance … cannibalizing the policies of the far-right Danish People’s Party to win back voters anxious about immigration.”[14]

Right-wing parties often attribute their popularity to their anti-migrant stance, which they claim many people share. The table opposite shows the significant rise of far-right parties in Europe between 2002 and 2017. But what it does not show is the incorporation of right-wing policies on migration and asylum into mainstream parties during the same period. Clearly, far-right parties no longer have a monopoly on restrictive, or anti-migrant and anti-refugee policies.

Moreover, such “right to exclude” advocates exist in academia too. Political philosopher David Miller, for example, justifies exclusionist immigration policies to defend community goals and preferences, and suggests (inaccurately) that irregular migrants engage in a “a form of queue-jumping with respect to all those who are attempting to enter through legal channels”.[15]

In European politics, “while the Left used to be less likely than the Right to discuss immigration in negative terms, in more recent years this difference has lessened. Far from polarizing, centrist parties’ treatment of the immigration issue is much closer to converging on key aspects of the debate.”[16] This convergence is likely to be important in shaping the future politics of migration.

Another stark example of the normalisation of blatant anti-migrant sentiment was provided by European Commission President-Elect Ursular von der Leyen’s September 2019 announcement that, as part of a “fresh start on migration”, the EU’s most senior official on migration issues would have the job title of “protecting our European way of life.” Much criticism ensued.[17]

Migration’s current position at the centre stage of politics thus stems from new forms of political competition driven by right-leaning or populist “political entrepreneurs”, rather than by any significant changes in individual attitudes to migration.[18] Some argue that by “fusing culturally conservative and anti-elite messages”, new life has been breathed into these populist political entities who use immigration as the central policy issue to “drive disruption and instability”.[19]

Single-issue dependency

The migration and asylum agendas of some political parties are normally linked to discussions of nativism, identity, ethnicity, and a mistrust of multiculturalism and multinationalism. But the dependency on enlarging and reiterating a migration “problem” and “threat” is often so great that it overshadows the rest of a party’s manifesto, which suggests that keeping the migration debate alive is essential to their own survival. Even if there is some cross-national convergence on other issues by far-right parties, the prevalence of migration in almost all public statements by leaders such as Hungary’s Viktor Orban or Italy’s Matteo Salvini in 2018 and 2019 is striking.

Despite such single-issue dependency, the appeal of such politicians and parties to voters is such that other political players are forced to take them seriously, leading them to become critical in coalitions and in some cases propelling them to the very top of the executive branch.

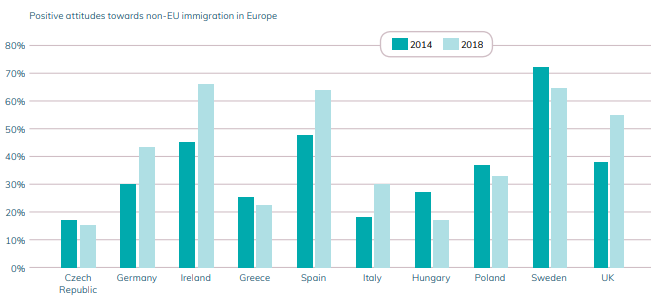

At the same time, opponents of such right-wing politics may engage in their own forms of distortion, by overstating not only the extent to which hardliners exploit or exaggerate migration issues, but also the degree of public aversion to anti-migrant narratives. As the graphic overleaf shows, tolerance of non-EU immigration is growing in Europe, but only in a few countries is this attitude held by more than half of the electorate. Besides, poll responses vary greatly between questions about labour migrants, irregular migrants, and refugees, and between those about temporary work permits and full citizenship. It is disingenuous to amalgamate nuanced and granular opinions into crude pro- or anti-migration categories. Unconscious bias can easily come into play and simplifying the debate or misrepresenting polls can be useful to both sides of the debate.

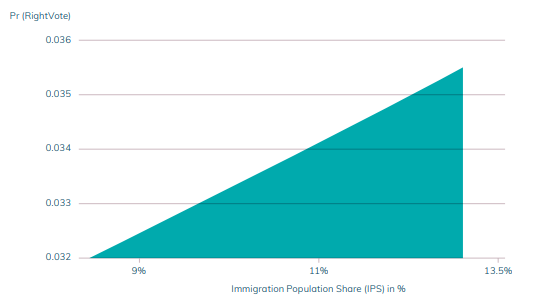

Immigrant share and the far-right rising together

A recent analysis of 14 European countries with at least one far-right party found “a strong positive relationship between the immigrant population share and the propensity of individuals to vote for a far-right party”.[20]

Of course, this finding does not preclude influence from far-right groups through campaigns to denigrate immigrant communities and blame them for their country’s troubles or problems as a way to boost their support base. Having more immigrants in society means the target of their campaigns is larger and more visible, making it easier to persuade people that immigrants pose a (socioeconomic, political, or security) threat, even if the evidence does not support this.

According to migration expert Ian Goldin and colleagues, attitudes towards migration can be distilled down to two sets of factors.[21] The first is solidarity – characterising the degree to which people identify and empathise with people of nationalities other than their own. Second, perceptions of aggregate scarcity – the degree to which key economic resources, such as public services and jobs, are seen to be under threat or pressure. “Anti-migrant attitudes are typically greatest when concerns about scarcity complement nationally defined limits of solidarity.”[22]

Vote share of far-right parties in National Elections in Europe (2002-2017)

Source: Goldin, I. & Nabarro, B. (2018) Losing it: The economics and politics of migration VOX CEPR Policy Portal.

Changing attitudes to EU immigration in Europe

Source: Oliviero Angeli

Normalisation of the extreme

In recent years, irrespective of the heat of the polemic surrounding refugees and migrants, and even with far-right parties unable to obtain mandates big enough to lead governments in all but a few countries, there is a new normalisation of policies and actions that would have been considered extreme a decade ago. The growing prevalence of the trends listed below raises the question, what will be considered politically acceptable in 10 or 20 years’ time?

• Growing prevalence of anti-immigration walls and fences between countries.

• Militarisation of border control and the deployment of soldiers or navies and externally financed coast guards to prevent mixed flows.

• Extensive use of detention – sometimes prolonged – of people on the move irregularly, including children and asylum seekers and registered refugees

• Extensive use of deportation of failed asylum seekers and “undocumented” migrants to countries where their safety cannot be assured.

• Pushbacks at land and sea borders – summarily returning refugees, asylum seekers and migrants.

• Failure to conduct appropriate search and rescue operations and preventing others doing so.

• Increased tolerance of abuse and death of migrants and asylum seekers on the move.

• Increased use of bilateral agreements with transit and origin countries to prevent mixed flows. •Increased criminalisation of irregular migrants, human smuggling and humanitarian assistance to those on the move.

• Reduced adherence to the 1951 Refugee Convention and reduced appetite for burden-sharing of asylum seekers and refugees.

All the trends listed above are explored in greater detail, with examples drawn from across the world, in the Info Box entitled Normalisation of the extreme on page 177 of the Mixed Migration Review 2019.

Talking the talk

Almost in direct contrast to these hard-line approaches, at the international level expressions of outrage at the deaths and violence that refugees and migrants face on the move, as well as of solidarity and cooperation, are not hard to find. In addition to the new focus on migration in the 2015 Sustainable Development Goals, the non-binding global compacts on migration and refugees set high standards and expectations on how the international community should address irregular migration and refugees. In December 2018, 152 countries voted in favour of the resolution to adopt the Global Compact for Migration, with the United States and Israel voting against, as did (following a “coordinated online campaign by far-right activists”) Hungary, the Czech Republic and Poland.[23] Twelve states abstained, including Austria, Switzerland and Italy. Meanwhile, the Global Compact on Refugees was approved by 181 states.[24]

The political zeitgeist and migration diplomacy

The above list of normalised “extremes” is not exhaustive but, seen together, it is an extraordinary testimony to recent developments that characterise the political zeitgeist and policy commitments concerning international irregular movement. In many cases these political choices have been and continue to be taken by open, democratic societies where human rights are otherwise highly valued and where the rule of law is firmly established. These are also some of the richest countries in the world, enjoying the highest human development indicators and state welfare protections.

In many cases, too, these approaches and actions are in direct opposition to the values and ethics in which the citizens of the countries involved take pride. This generalised normalisation of radical or extreme policy is a key feature of contemporary political approaches to irregular and mixed migration and, importantly, may offer clues as to how the future will look irrespective of the role of far-right politics.

The notion of migration diplomacy conceptualises a new development in interstate negotiations in which migration is a powerful bargaining tool. It highlights “the multiple effects of cross-border population mobility – not merely on numerous aspects of domestic politics but also on states’ international relations.”[25] For example, in September 2019, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan warned he would “open the gates” to allow Syrian refugees to leave Turkey for Europe if he did not get more international support for the creation of a “safe zone” in north-eastern Syria.[26] Another well-documented earlier example was Libyan leader Muammar Gadaffi’s threat in 2010 to “turn Europe black” by lifting restrictions on African migration to Europe through Libya unless payments were received.[27] Given the likelihood that migration will only increase in its importance to states and their policymakers in the coming decades, the salience of migration diplomacy is set to increase.

The less publicised ‘zeitgeist’

While many countries are busy trying to prevent irregular migrants and asylum seekers from accessing their territory and are reducing their intake of refugees for resettlement, another reality is being played out. Countries in the Middle East, South East Asia and Africa, as well as Venezuela’s neighbours in South America, are accepting and hosting over 85 percent of the millions of refugees worldwide and allowing the movement of millions of irregular migrants. In the case of Colombia, over 1.4 million Venezuelan refugees have been allowed to enter the country, to work, access welfare and schools.[28] Even citizenship is being granted to tens of thousands of babies born Venezuelan refugees.[29] This is an alternative political zeitgeist that exists alongside the more publicised, global North preoccupation with and operationalisation of anti-migrant and anti-refugee efforts.

The majority of the 26 million refugees today come from six countries: Syria, Afghanistan, South Sudan, Somalia, Myanmar and Venezuela. They are hosted in countries such as Lebanon, Turkey, Jordan, Pakistan, Iran, Sudan, Uganda, Ethiopia, Kenya, Yemen, Colombia, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Bangladesh – all developing or low-to-medium income countries.

Close behind these is one European exception, Germany, that has recently taken in more than one million refugees – a unilateral political decision that is at the heart of the migrant and refugee political “crisis” of 2015 and 2016 and whose political ramifications are still being felt in terms of interstate disputes around responsibility sharing, border management and the move to the right in EU politics generally. Nevertheless, despite German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s declining support and the rise of the anti-migrant AFD party, polls suggest that German popular support for a multicultural society has grown since 2015 (also see the graphic on page 175).[30]

Furthermore, in terms of irregular migrants, the volume of South-to-South movement is far greater than that testing the politicians of the global North. While many countries of the global South do not have the capacity to prevent irregular migration they also turn a blind eye to it as they benefit from the labour and entrepreneurship migrants and urban refugees bring. Countries such as Thailand, Malaysia, Kenya, and (notwithstanding sporadic bouts of xenophobic violence) South Africa are ready examples. This is, in fact, an important long-standing trend that needs to be considered when imagining the future of migration and refugee politics.

Future scenarios: a tale of two worlds?

Given how far political and practical reactions to irregular movement and asylum differ between the global North and South, their respective future trends can be discussed separately, even though their futures are, of course, inextricable entwined.

The North’s new normal

Concerning the global North, we can surmise that even if the far-right fails to make significant political gains, the increasingly restrictive and securitised responses to irregular mixed movement that have become part of mainstream politics and constituent expectations will become entrenched as a new normal. This is the most likely course for the short- and medium-term future, despite the international aspirations laid out in recent agreement on migrants and refugees. As noted earlier in this essay, cross-national attitudes towards migration are often unconnected to actual economic necessities and labour demand – instead they are shaped by a perception of the threats migration poses to the economy, social cohesion and cultural values. As such, attitudes are often more an expression of prejudices and imagined fears than of reality. These perceptions could generate real economic risks, while a “race to the bottom by politicians to show how tough they are on immigration could cause substantial aggregate damage.”[31]

Additionally, as current contested and controversial interventions and actions continue to thwart irregular migration in many regions, they are likely to become increasingly accepted. They will become the political and operational reality for the future as they are already becoming today. Containing and warehousing irregular migrants and asylum seekers outside the global North may become increasingly expensive for the North, not least as the strength of the migration diplomacy of the South increases, but it will likely become the preferred option over relaxing borders or increasing asylum acceptance.

More of the same to come?

The uncertainty around automation and artificial intelligence and their impact on the economy and employment in the global North may intensify domestic pressure to prevent higher levels of migration, especially in the case of medium and low-skilled migrants. However, in light of declining fertility and increased ageing in the North ahead of major technological transformations springing from automation, there may eventually also be a surge in demand for labour migration. If these forces are greater than the electorate’s low appetite for increased migration, future political trends may in fact reverse in the short and medium-term. An extension and continuation of the current political approach is therefore not inevitable, but according to the prognosis of this essay, more likely.

Questions of age

Generational differences could also impact future trends in the global North. Today’s youth live in increasingly diverse societies and will be tomorrow’s leaders and voters, and will be more multicultural and less anti-migration.[32] This could soften the current hard-line attitude towards irregular migrants and refugees in the future, although some studies contend that education, and exposure to right wing messaging, are better predictors of attitudes than age alone.[33] A recent analysis of national populism, on the other hand, suggests we cannot rely on more tolerant attitudes from the youth – who are not so much anti-immigrant but populist in inclination – as they react against traditional politics, so-called elites, and find themselves part of a larger modern trend of social fragmentation.[34] Furthermore, even if young people are less prone to anti-migrant attitudes, they also age and tend, on average, to become more conservative.[35]

Already, despite the phenomena, in Europe at least, of right wing attitudes rising as the immigrant share in a country increases (see Graphic 1), there is also evidence that attitudes can change positively towards non-EU immigrants even during a turbulent period when the issues were hotly contested.

Manufacturing rage

Graphic 2 shows findings illustrating how in most countries in Europe positive attitudes to non-EU immigration increased between 2014 and 2018, even in the UK where migration was recorded as among the most prominent issues that set the UK on a course to leave the European Union during the 2016 Brexit referendum. This may seem paradoxical given the sense of panic and crisis that the media portrays around the subject in recent years by focusing on the most dramatic and chaotic scenes and telling the most desperate stories.[36] Such coverage has helped to “manufacture rage” against migration and made good revenues too by keeping dramatic migration and refugee stories on the front pages.[37] Social media and the internet have also been key channels for propaganda on refugee and migration issues, thriving on extreme news and failing to prevent false narratives.[38]

Immigrant population share and far right voting (average relationship between 2004-2017 using 14 EU countries)

Source: Goldin, I. & Nabarro, B. (2018) Losing it: The economics and politics of migration VOX CEPR Policy Portal.

The sheer force of numbers of potential migrants and displaced people in the future could exert pressure on the global North, not least when large numbers of climate-induced migrants start to move. In tandem with the increasing strength of Southern countries’ hand in migration diplomacy, this could also force the global North to adopt a softer political position in relation to mixed migration and regular labour migration. On the other hand, increased pressure and rising fear that migratory pressures will overwhelm countries in the global North are also likely to cause them to double down on restriction and preventing access.

A future with few choices in the global South

Concerning the global South, where almost all the world’s internally displaced people reside, from where most irregular migrants originate, and where almost all refugees are hosted, it is hard to see how the future will offer many choices. Predictions are that millions of climate-induced migrants and displaced will originate in the global South and will initially move within their countries (mainly to cities) or move regionally before considering (if they have the capacity) to move out of their regions.

Many countries in the South – especially those with long porous borders and weak institutions, where corruption and complicity often lead state officials to prey upon those on the move – lack the capacity to prevent movement. Even if they have the requisite will, and regardless of how far countries in the global North try to co-opt or buy their support for an anti-migration agenda, such countries may simply be unable to stop North-bound migrants transiting their territory.

As cities grow rapidly in the South, especially in Africa, they will become ever stronger magnets for the displaced and irregular migrants. This might boost their economic capacity with cheap labour, but might also cause social tensions as the growing national youth cohort competes with the newly-arrived for jobs, services and space. If the global North maintains strong barriers to migrants, and resists more equitable global burden-sharing of refugees, dynamic South-to-South movement is likely to ensue as people seek improved security and viable livelihoods. Urban refugees are more numerous than those living in camps today and this is likely to be the future trend in host countries in the South – assuming they continue to be tolerated.

Migration and populism

Some social commentators and researchers like to say immigration is a red herring. “It’s not about immigration, the financial crisis, globalisation or inequality, but evidence of a broader, older social fragmentation,” claims one analyst.39 What he and others are writing about is the rise and probable future extent of populism, national populism to be specific. According to a recent book on the subject, it is not the actual number of immigrants (or the current state of the world in general), but the rate of change over time that drives support for national populism.[40] Populism “represents the cumulative effect of growing differences between political elites and those they represent, the death of traditional political ties and cultural responses to both globalisation and immigration.”[41] The forces that have led to the recent rise in national populism are not temporary, but “part of decades-strong currents. It doesn’t look like they’re going anywhere anytime soon.”[42] If anti-immigration sentiment becomes part of future populism, will acceptance of the “normalisation of the extreme” and reinforcement of these approaches also be considered necessary to secure perceived national interests or identity?

Conclusion

The politics of migration and refugees is set to be more hostile than accommodating. With growing economic migratory pressures and the likelihood that increased political and environmental fragility will cause higher levels of forced migration, the global North will probably double down on current efforts to restrict access and mobility towards their territories. Permitted movement will be selective (consisting predominantly of high-skilled workers) and limited. Most of the pressures of rising numbers of displaced, unemployment, overcrowded cities, resource scarcity and refugee-hosting will be faced by the global South. Will these pressures cause more intolerant and authoritarian politics in the South, leading to further fragility and insecurity and humanitarian crises? Overall, the language of international agreements, and their professed political commitment to solidarity, cooperation and responsibility-sharing, appears quixotic.

[1] Castles, S., de Haas, H. & Miller, M. (2014) The Age of Migration: International Population Movements in the Modern World London: Palgrave Macmillan

[2] Bieber, F. (2018) Is Nationalism on the Rise? Assessing Global Trends.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Goldin, I. & Nabarro, B. (2018) Losing it: The economics and politics of migration VOX CEPR Policy Portal

[6] Ibid.

[7] Davis, L. & Deole, S. (2017) Immigration and the Rise of Far-Right Parties in Europe ifo Institute; MacKenzie, D. (2016) The truth about migration: How it will reshape our world New Scientist

[8] Duara, P. (2018) Development and the crisis of global nationalism Brookings

[9] Horwood, C. (2019) It’s Time for a More Honest, Less Partisan Debate on Mixed Migration Refugees Deeply

[10] On the campaign trail in 2015, Trump said, “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best… They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And some, I assume, are good people.” In 2018 he said of undocumented migrants, “These aren’t people. These are animals.” Korte, G. & Gomez, A. (2018) Trump ramps up rhetoric on undocumented immigrants: ‘These aren’t people. These are animals.’ USA Today

[11] Cooke, P. (2018) Sweden swings right – Swedish election sees neo-Nazi Democrats make huge gains as mass immigration leaves Sweden bitterly divided The Sun

[12] Sanandaji, D. (2018) The cost of Sweden’s silent consensus culture Politico

[13] Orange, R. (2019) Mette Frederiksen: the anti-immigration left leader set to win power in Denmark The Guardian

[14] Hume, T. (2019) Denmark’s Elections Show How Much Europe Is Normalizing Anti-Immigrant Politics Vice

[15] Miller, D. (2016) Strangers in Our Midst: The Political Philosophy of Immigration Harvard University Press. For a critique of Miller, see Sager, A. Book Review: Strangers in Our Midst: The Political Philosophy of Immigration by David Miller LSE Review of Books

[16] Dancygier, R. & Margalit, Y. (2017) The Evolution of the Immigration Debate: A Study of Party Positions over the Last Half-Century Princeton (working paper)

[17] Rankin, J. (2019) MEPs damn ‘protecting European way of life’ job title The Guardian

[18] Goldin, I. & Nabarro, B. op. cit.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Goldin, I. & Nabarro, B. op. cit.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Cerulus, L & Schaart, E. (2019) How the UN migration pact got trolled Politico. For more on how right-wing activists use the internet and social media during election campaigns and beyond, see: ISD (2019) The Battle for Bavaria – Online information campaigns in the 2018 Bavarian State Election Gallagher, C. & Pollack, S. (2019) How the far-right is exploiting immigration concerns in Oughterard Irish Times

[24] UN News (2018) UN affirms ‘historic’ global compact to support world’s refugees

[25] Adamson, F. & Tsourapas, G (2018) op. cit.

[26] BBC (2019) Syria war: Turkey warns Europe of new migrant wave

[27] Traynor, I. (2010) EU keen to strike deal with Muammar Gaddafi on immigration The Guardian

[28] Baddour, D. (2019) Colombia’s Radical Plan to Welcome Millions of Venezuelan Migrants The Atlantic

[29] Kurmanaev, A. & Gonzales, J. (2019) Colombia Offers Citizenship to 24,000 Children of Venezuelan Refugees New York Times

[30] DW (2018) Germans upbeat about immigration, study finds

[31] Ian Goldin, I. & Nabarro, B. op. cit.

[32] McLaren, L. et al. (2019) Anti-immigration attitudes are disappearing among younger generations in Britain King’s College London

[33] Mclaren, M. & Paterson, T. (2019) Generational change and attitudes to immigration Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies

[34] Goodwin, M. (2018) National populism is unstoppable – and the left still doesn’t understand it The Guardian

[35] Tilley, J. & Evans, G. (2014) Ageing and generational effects on vote choice: Combining cross-sectional and panel data to estimate APC effects Electoral Studies

[36] Trilling, D. (2019) How the media contributed to the migrant crisis The Guardian

[37] Mehta, S. (2019) Immigration panic: how the west fell for manufactured rage The Guardian

[38] Koppelman, A. (2019) The internet is radicalizing white men. Big tech could be doing more CNN

[39] Goodwin, M. (2018) op. cit.

[40] Eatwell, R. & Goodwin, M. (2018) National Populism: The Revolt Against Liberal Democracy London: Pelican Books

[41] Spiro, Z. (2018) Review: National Populism, by Roger Eatwell and Matthew Goodwin Institute of Economic Affairs

[42] Ibid.