The following essay was originally compiled for the Mixed Migration Review 2018 and has been reproduced here for wider access through this website’s readership.

Any meaningful understanding of migration must tackle head-on two key questions: Under what conditions do people develop aspirations to migrate? And, under what conditions are they able to realize those aspirations?

These are questions that dominate the recent findings of migration scholars across various disciplines, including anthropology, sociology, economics, and human geography. Drawing on this body of work and 4Mi data, this essay offers some comment and overview of current understandings of drivers of mixed migration as defined by aspirations and capacities, as well as of the game-changing rise of migrant smuggling as a major facilitator of irregular movement.

Hot topic

Recently, exploring drivers and root causes has taken centre stage in the field of migration studies. This is a direct result of the political and social disquiet in Europe that followed the surge of new, irregular, arrivals of refugees and migrants since 2015. Spurred by the heightened attention of politicians, policy makers, and news media, and energized by fresh injections of research funding, academics and others have redoubled their efforts to explain mobility.

In late September 2018, the European Union’s Joint Research Centre (JRC) published International Migration Drivers, presenting the results of a two-year study using a quantitative assessment of the structural factors shaping migration. Full of rich findings and nuance reflecting the complexity of the subject, the report confirms that the key drivers of international migration are mainly structural: economic development in countries of origin, as well as migrants’ social networks, geographical proximity and demographic change.

To some extent the report is emblematic of the search for answers to a question often posed in (mostly northern) destination countries: “Why do they come?” For some, the corollary to this question is, of course, “How can we stop them?” The prominence of these preoccupations explains why the search for drivers is such a hot topic politically.

In addition to presenting a summary of different migration theories and insights offered over recent decades, the statistical findings of the JRC report reaffirm many of the newer theories posited by migration scholars, such as, the critical role of the Diaspora and network theories, and migration transition theories about the relationship between development and migration.

The report’s message to policy-makers in particular is blunt: their capacity to influence migration is limited. Restrictive policies do not change the scale of migration as much as they do the manner in which people migrate. This means if refugees and migrants are to stand a chance of succeeding in the current restrictive environment they will increasingly need to travel irregularly.

The importance of nuance

Terms such as migrant aspirations and desires are increasingly used by theorists and analysts to explain what have also been described as push-pull factors, determinates, root causes, and causality for human mobility. All too often, the media, politicians and activists link forced (and other forms of desperation) migration only with conflict and endemic poverty. Although threats to physical security and an inability to thrive must be recognised as powerful factors in migration decision making, a fuller understanding of drivers needs to delve beyond such dualistic explanations.

Such “war or poverty” dualism reveals little of migration’s complexities and the manner in which it is embedded in aspirations. Instead, theories around drivers need to account for the “multiplex componentry of migration, the way it is situated in imaginative geographies, emotional valences, social relations and obligations and politics and power relations, as well as in economic imperatives and the brute realities of displacement.” Otherwise, there is a “great risk”, not only in “reproducing stereotypes of migrants as individual and collective subjects, but also in bolstering repressive approaches to policing movement”. Equally, some exploration of the importance of desire in mobility suggests a more progressive process, where various factors and influences come into play at different times.

Blurred lines

Another kind of dualism — between forced and voluntary migration — is coming also under increasing scrutiny in the light of the complexity of the drivers involved in decisions to migrate. In one recent paper, analysts examine voluntariness in migration decisions and suggest that forced and voluntary migration are understood better as points on a spectrum than as a dichotomy.

Such blurred lines are particularly evident in regions such as sub-Saharan Africa. A recent qualitative survey of 500 refugees and migrants in Europe found “there is often a complex and overlapping relationship between ‘forced’ and ‘economic’ drivers of migration to Europe. Many of those who left their home countries primarily due to economic reasons effectively became refugees and were forced to move due to the situation in Libya and elsewhere.”

Disparate drivers

Irregular movement, normally involving facilitators and smugglers, is at the heart of the phenomenon of mixed migration (defined as complex flows in which refugees, asylum seekers, economic migrants, “desperation migrants”, “aspiration migrants”, “environmental refugees” and others travel together irregularly.) “Others” may include people inspired by adventurism or simple wanderlust, or those yearning for personal freedoms which their own societies are not ready to offer — in other words, a desire to shrug off social, cultural, religious, political or sexual constraints.

Unofficial terms or categories such as these are not found in formal definitions of migrants and refugees yet they speak to the aspirations and desires of those on the move. Those who work with refugees and migrants understand that these terms offer a more realistic testimony to the wide variety of drivers behind individual decisions to move. As shown in Graph 4 in this article even though ultimately most 4Mi respondents say they made the decision alone, those who say they were encouraged to migrate list a wide variety of people and factors, ranging from friends, parents, siblings, spouses and other family, to those in the Diaspora and smugglers.

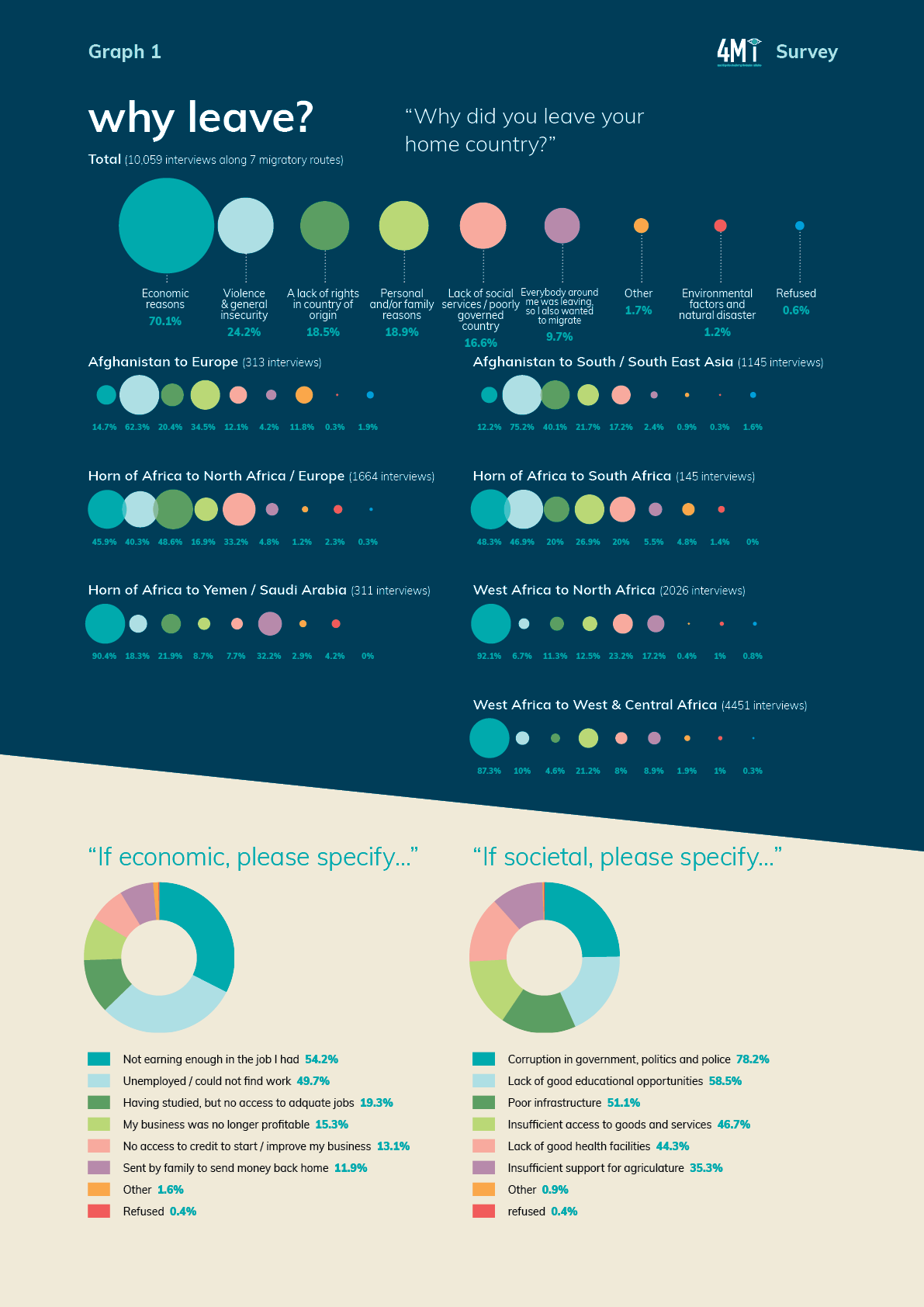

4Mi data show that although economic factors are often crucial drivers, there is indeed a very wide variety of others, linked to violence and insecurity, lack of rights, poor governance and personal circumstances (see Graph 1).

Dig deeper

Furthermore, even driver categories such as economic or lack of rights tend to generalize and so demand further in-depth investigation. As shown in Graph 1, on all routes, the most commonly cited specific example of an economic reason to migrate is “not earning enough in the job I had” (54.2 percent), followed by “unemployed” (49.7 percent) and “having studied but no access to adequate jobs” (19.3 per cent). This shows it is not just unemployment that drives people to leave. Many in mixed migration flows did have jobs before moving, but not satisfying jobs. In another example that showed the rewards of digging deeper, 78.2 percent of respondents on all routes who cited a lack of social services or poor governance said corruption was a major factor.

Driven along different routes

People on different mixed migration routes may have different drivers. Migration from West Africa is to a large extent driven by economic reasons, while movement from Afghanistan is more strongly related to violence and insecurity, as shown in Graph 1. However, the data also show that these motivations vary according to the different routes people from the same country or region take. Those on the route from the Horn of Africa towards Yemen and Saudi Arabia, for example, are primarily moving for economic reasons (90.4 per cent), while those moving from the Horn towards North Africa and Europe are also moving because of a lack of rights. This might be related to what people expect to find in their preferred destination countries. In fact, other 4Mi findings on why people in mixed migration flows choose certain destinations offers a mirror image of these drivers.

Those in mixed flows are rational actors and mostly choose destinations on the basis of available knowledge about the situation in those countries. For example, as also shown in Graph 3 below, respondents from the Horn of Africa moving towards Yemen and Saudi Arabia go there to find a job and send remittances back home (93 percent), but do not have high expectations about personal and political freedom or access to healthcare or social welfare. Conversely, respondents on the route from Afghanistan to South East Asia reported they had left in search of better living standards, more freedom and better services, but did not expect to find a very open job market at their destination.

Blinkered thinking

The repeated fixation on war and poverty as the (only) core drivers of mixed migration patronises those on the move and inhibits a full grasp of the diverse range of issues in play. These issues come to light when those on the move are asked what in their lives would need to improve for them to have considered remaining in their country of origin. As shown in Graph 2, across all migration routes, 4Mi respondents list a whole range of issues, both structural and individual. On some routes, the percentages relating to each of these issues are quite similar, although on some routes (e.g. from the Horn of Africa to Saudi Arabia, or from West Africa to West and Central Africa), “financial circumstances” does stand out. Clearly, if there were no war and less poverty there would still be many other aspects that affect people’s aspirations to move.

4Mi data also reveal the strength of migration drivers and aspirations. People in mixed migration flows face severe risks. Depending on where they are interviewed — at which point in their journey — between one third and two thirds (the latter in the case of those who travelled from West Africa all the way up to the Libyan coast) of all respondents report having experienced sexual violence, physical violence, robbery or kidnapping. Despite the prevalence of these abuses, almost 70 percent of all (9,846) respondents said they would migrate again, even knowing what they know now.[1] At the same time, almost 60 percent of the same respondents said knowing what they know now they would not encourage others to migrate. Though open to multiple interpretations, this shows how migration is an individual project, and that the fact that one person is willing to take risks and sometimes to pay a high price for migrating does not mean that he or she would encourage others to do the same.

Smugglers as game-changers

The “institutional” approach to understanding contemporary movement focusses on networks and facilities that spring up and develop alongside international migration and which play an important role in nurturing and encouraging capabilities for further migration. Here, the imbalance between the number of people who wish to migrate and the restriction of visas or other legal channels to enter destination countries has contributed to the “migration economy” and a specific market, whose “suppliers” range from immigration attorneys, travel and recruitment agencies, to migrant smugglers (itself a sector with numerous kinds of actor).

For mobility to be successful, aspirations must be matched by capabilities. In this regard, the rapid growth in recent years of an informal migration industry led by smugglers is a game-changer. It is easy to see how, notwithstanding other influencing factors, the supply and demand side of mobility through irregular pathways has ratchetted forward, with increased demand (from refugees and migrants) responding to a growing supply (of enabling smugglers), reinforcing and expanding the space for mixed migration.

Of course, not everyone with aspirations and desires to move has the capabilities to do so. Statistical variations in the much-cited global Gallup poll on migration between those who would like to migrate, those who are preparing to migrate, and those who actually do migrate are huge. Between 2010 and 2015, around 30 percent of the population of 157 countries around the world expressed a wish to move abroad, while fewer than one percent have in fact migrated.1 But as restrictions increase — limiting previously-available regular channels for employment, family reunification and education — the role of irregular channels and the migrant smugglers who facilitate mixed flows grows in tandem.

Smugglers as democratisers

The drivers and aspirations of all people on the move, whether they are in South-to-South or South-to-North, in regular or irregular movements, have many similarities, but their specificities are shaped by personal circumstances and individual desires. So too with capabilities. Asked what might stop them migrating, 4Mi respondents across all routes (N=6,915) most commonly answer “lack of funds” (58 per cent) and “protected borders” (44 percent), clearly pointing to the importance of capabilities.[2]

But the growth of migrant smuggling has opened extraordinary opportunities to some who may not previously have had the ability to migrate or to apply for asylum through regular means. 4Mi data show that high percentages of respondents use smugglers during migration, especially along some of the longer routes, such as Horn of Africa to South Africa (86 percent), West Africa to North Africa (73 percent) and Horn of Africa towards North Africa and Europe (66 percent).

Migrant smuggling offers those with aspirations alternatives for mobility in an increasingly restrictive context. It also levels the playing field and could be said to democratise migration by enabling those without sufficient agency or capacity to move, notwithstanding that many feel compelled to move and have no other option but to use smugglers and travel irregularly.

How aspirations and desires to migrate are shaped in the future will be a direct result of macro, meso and micro factors in countries of origin, transit and destination. They will change over time, just as capabilities and opportunities, regular or irregular, to facilitate mobility will change. For now, however, it is clear that irregular pathways offer many of those in mixed migration the only viable alignment between their aspirations and capabilities.

[1] Responses vary by route, seemingly depending on the severity and prevalence of risks; for example, close to 60 percent of West Africans interviewed in Libya answer ‘no’ to this question

[2] This question was not asked in North Africa and therefore this finding does not include refugees and migrants interviewed in Libya.