How Spain Became the Top Arrival Country of Irregular Migration to the EU

This article looks at the increase in arrivals[1] of refugees and migrants in Spain, analysing the nationalities of those arriving to better understand whether there has been a shift from the Central Mediterranean migration route (Italy) towards the Western Mediterranean route (Spain). The article explores how the political dynamics between North African countries and the European Union (EU) have impacted the number of arrivals in Spain.

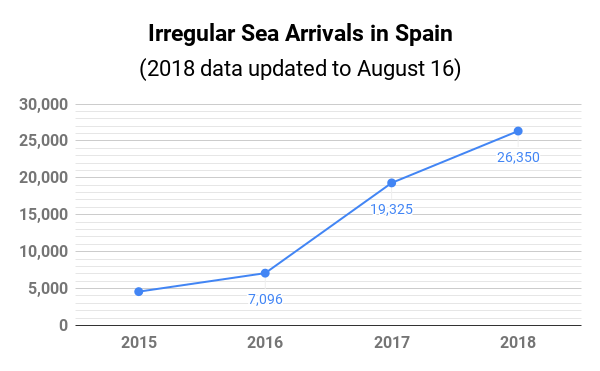

The Western Mediterranean route has recently become the most active route of irregular migration to Europe. As of mid-August 2018, a total of 26,350 refugees and migrants arrived in Spain by sea, three times the number of arrivals in the first seven months of 2017. In July alone 8,800 refugees and migrants reached Spain, four times the number of arrivals in July of last year.

But this migration trend did not begin this year. The number of refugees and migrants arriving by sea in Spain grew by 55 per cent between 2015 and 2016, and by 172 per cent between 2016 and 2017.

Data source: UNCHR & IOM

At the same time, there has been a decrease in the number of refugees and migrants entering the EU via the Central Mediterranean route. Between January and July 2018, a total of 18,510 persons arrived in Italy by sea compared to 95,213 arrivals in the same period in 2017, an 81 per cent decrease.

This decrease is a result of new measures to restrict irregular migration adopted by EU Member States, including increased cooperation with Libya, which has been the main embarkation country for the Central Mediterranean migration route. So far this year, the Libyan Coast Guards have intercepted 12,152 refugees and migrants who were on smuggling boats (more than double the total number of interceptions in 2017). In the last two weeks of July, 99.5 per cent of the refugees and migrants who departed on smuggling boats were caught and returned to Libya, according to a data analysis conducted at the Italian Institute for International Political Studies (ISPI). The number of people being detained by the Libyan Directorate for Combatting Illegal Migration (DCIM) has continued growing (from 5,000 to 9,300 between May and July 2018), with thousands more held in unofficial detention facilities.

So, was there a shift from the Central to the Western Mediterranean Migration route? In other words, has the decline of arrivals in Italy led to the increase of arrivals in Spain?

First of all, while this article only analyses the changes in the use of these two sea routes and among those trying to go to Europe, for most West Africans, the intended destination is actually North Africa, including Libya and Algeria, where they hope to find jobs. A minority intends to move onwards to Europe and this is confirmed by MMC’s 4Mi data referred to below.

The answer to the question on whether or not there has been a shift between the two routes can be found in the analysis of the origin countries of the refugees and migrants that were most commonly using the Central Mediterranean route before it became increasingly difficult to reach Europe. Only if a decrease of the main nationalities using the Central Mediterranean Route corresponds to an increase of the same group along the Western Mediterranean route we can speak of “a shift”.

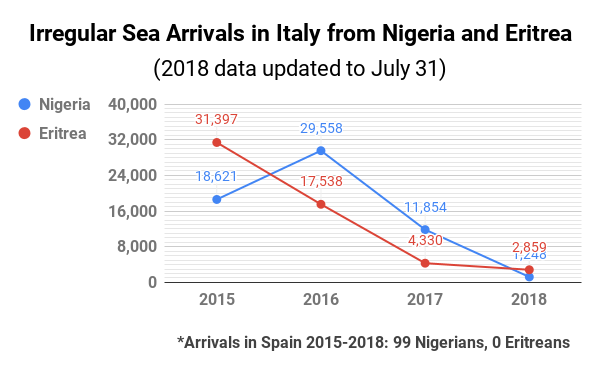

The two nationalities who were – by far – the most common origin countries of refugees and migrants arriving in Italy in 2015 and in 2016 were Nigeria and Eritrea. The total number of Nigerians and Eritreans arriving in Italy in 2015 was 50,018 and slightly lower (47,096) in the following year. Then, between 2016 and last year, the total number of Nigerian and Eritrean arrivals in Italy decreased by 66 per cent. The decrease has been even more significant in 2018; in the first half of this year only 2,812 Nigerians and Eritreans arrived in Italy.

However, there has not been an increase in Nigerians and Eritreans arriving in Spain. Looking at the data, it is clear that refugees and migrants originating in these two countries have not shifted from the Central Mediterranean route to the Western route.

Data source: UNCHR & IOM

The same is true for refugees and migrants from Bangladesh, Sudan and Somalia – who were also on the list of most common countries of origin amongst arrivals in Italy during 2015 and 2016. While the numbers of Bangladeshis, Sudanese and Somalis arriving in Italy have been declining since 2017, there has not been an increase in arrivals of these nationals in Spain. Amongst refugees and migrants from these three countries, as with Nigerians and Eritreans, there has clearly not been a shift to the Western route. In fact, data shows that zero refugees and migrants from Eritrea, Bangladesh and Somalia arrived in Spain by sea since 2013.

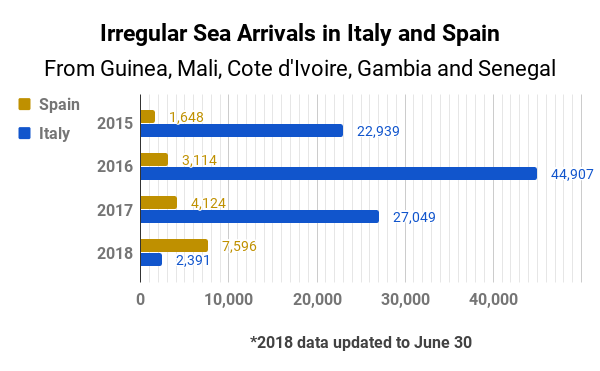

However, the data tells a different story when it comes to West African refugees and migrants. Between 2015 and 2017, the West African countries of Guinea, Mali, Cote d’Ivoire, Gambia and Senegal were also on the list of most common origin countries amongst arrivals in Italy. During those years, about 91 per cent of all arrivals in the EU from these five countries used the Central Mediterranean route to Italy, while 9 per cent used the Western Mediterranean route to Spain.

But in 2018 the data flipped: only 23 per cent of EU arrivals from these five West African countries used the Central Mediterranean route, while 76 per cent entered used the Western route. It appears that as the Central Mediterranean route is being restricted, a growing number of refugees and migrants from these countries are trying to reach the EU on the Western Mediterranean route.

Data source: UNCHR & IOM

These finding are reinforced by 3,224 interviews conducted in Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso between July 2017 and June 2018 by 4Mi, the data collection programme of MMC, which found a rise in the share of West African refugees and migrants stating their final destination is Spain and a fall in the share of West African refugees and migrants who say they are heading to Italy.[2]

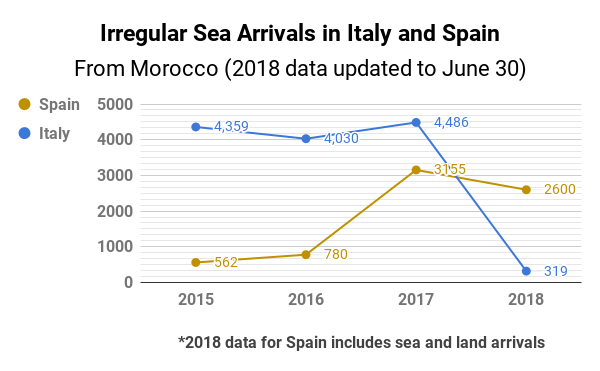

A second group who according to the data shifted from the Central Mediterranean route to the Western route are the Moroccans. Between 2015 and 2017, at least 4,000 Moroccans per year entered the EU on the Central Mediterranean route. Then, in the first half of this year, only 319 Moroccan refugees and migrants arrived by sea to Italy. Meanwhile, an opposite process has happened in Spain, where the number of Moroccans arriving by sea spiked, increasing by 346 per cent between 2016 and last year. This increase has continued in the first six months of this year, in which 2,600 Moroccans reached Spain through the Western Mediterranean route.

Data source: UNCHR & IOM

On-going Political Bargaining

The fact that so many Moroccans are amongst the arrivals in Spain could be an indication that Morocco, the embarkation country for the Western Mediterranean route, has perhaps been relaxing its control on migration outflows, as recently suggested by several media outlets. A Euronews article questioned whether the Moroccan government is allowing refugees and migrants to make the dangerous sea journey towards Spain as part of its negotiations with the EU on the size of the support it will receive. Der Spiegel reported that Morocco is “trying to extort concessions from the EU by placing Spain under pressure” of increased migration.

The dynamic in which a neighbouring country uses the threat of increased migration as a political bargaining tool is one the EU is quite familiar with, following its 2016 deal with Turkey and 2017 deal with Libya. In both occasions, whilst on a different scale, the response of the EU has been fundamentally the same: to offer its southern neighbours support and financial incentives to control migration.

The EU had a similar response this time. On August 3, the European Commission committed 55 million euro for Morocco and Tunisia to help them improve their border management. Ten days later, the Moroccan Association for Human Rights reported that Moroccan authorities started removing would-be migrants away from departure points to Europe.

Aside from Morocco and Libya, there is another North African country whose policies may be contributing to the increase of arrivals in Spain. Algeria, which has been a destination country for many African migrants during the past decade (and still is according to 4Mi interviews), is in the midst of a nationwide campaign to detain and deport migrants, asylum seekers and refugees.

The Associated Press reported “Algeria’s mass expulsions have picked up since October 2017, as the European Union renewed pressure on North African countries to discourage migrants going north to Europe…” More than 28,000 Africans have been expelled since the campaign started in August of last year, according to News Deeply. While Algeria prides itself on not taking EU money – “We are handling the situation with our own means,” an Algerian interior ministry official told Reuters – its current crackdown appears to be yet another element of the EU’s wider approach to migration in the region.

Bargaining Games

This article has demonstrated that – contrary to popular reporting – there is no blanket shift from the Central Mediterranean route to the Western Mediterranean route. A detailed analysis on the nationalities of arrivals in Italy and Spain and changes over time, shows that only for certain nationalities from West Africa a shift may be happening, while for other nationalities there is no correlation between the decrease of arrivals in Italy and the increase of arrivals in Spain. The article has also shown that the recent policies implemented by North African governments – from Libya to Morocco to Algeria – can only be understood in the context of these countries’ dialogue with the EU on irregular migration.

So, while the idea of a shift from the Central Mediterranean route to the Western route up until now is more myth than reality, it is clear that the changes of activity levels on these migration routes are both rooted in the same source: the on-going political bargaining on migration between the EU and North African governments. And these bargaining games are likely to continue as the EU intensifies its efforts to prevent refugees and migrants from arriving at its shores.

1. In this article, the focus is on refugees and migrants arriving by sea after crossing the Mediterranean irregularly.

2. Due to the 4Mi methodology of purposive sampling, its findings cannot be viewed as conclusive evidence, but given the relatively large sample size it does provide a good indication of trends.